|

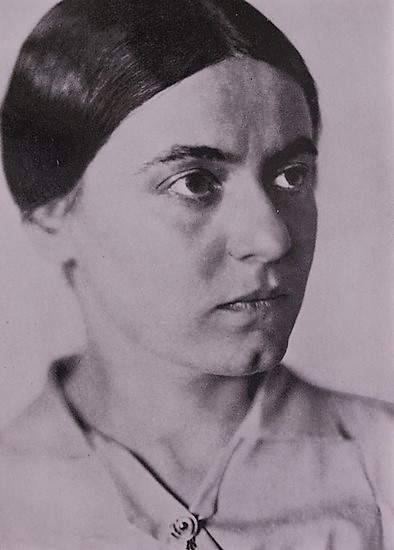

Edith Stein (1891–1942) |

THEMES ON THIS PAGE:

| 1. EMPATHIC UNDERSTANDING | 2. SHAPING MY BELIEF | 3. | 4. |

Edith Stein was a German philosopher, a student of Edmund Husserl, the father of Phenomenology. She wrote her PhD dissertation with him, but she was also in communication with important thinkers such as Heidegger, Scheler, and others.

Edith Stein was a German philosopher, a student of Edmund Husserl, the father of Phenomenology. She wrote her PhD dissertation with him, but she was also in communication with important thinkers such as Heidegger, Scheler, and others.

Stein was born to a Jewish family. Initially she was not religious, but after her doctorate, in her forties, she converted to Catholicism and became a nun in 1933. After the rise of the Nazis, her convent transferred her to another convent in Holland in order to protect her. In Holland she continued to write philosophical and religious writings. When Holland was conquered by Germany, she was arrested by the Gestapo in 1942, sent to Auschwitz, and was murdered a few days later. In 1988 she was canonized by the Pope as a Catholic saint, although the controversy continues on whether she was killed by the Germans as a Jew or as a nun.

|

TOPIC 1: EMPATHIC UNDERSTANDING |

Edith Stein wrote her essay ON THE PROBLEM OF EMPATHY (1917) as a PhD dissertation in philosophy, but this work was taken seriously and quoted by other thinkers of the time. It was written in the spirit of phenomenology, in other words exploring the structure of our experience (as opposed to hidden psychological mechanisms or processes). The central issue of this work is how we achieve empathic understanding of other people. How do I comprehend that Linda is sad, or that she likes my shirt, or that she believes in God, or that she is a shy person?

Edith Stein wrote her essay ON THE PROBLEM OF EMPATHY (1917) as a PhD dissertation in philosophy, but this work was taken seriously and quoted by other thinkers of the time. It was written in the spirit of phenomenology, in other words exploring the structure of our experience (as opposed to hidden psychological mechanisms or processes). The central issue of this work is how we achieve empathic understanding of other people. How do I comprehend that Linda is sad, or that she likes my shirt, or that she believes in God, or that she is a shy person?

For Stein, empathic understanding is complex, and it contains several aspects. Nevertheless, it is a unitary act of understanding that is not made of step-by-step thinking and calculating. Empathy presents to me your emotions (thoughts, desires, beliefs, personality, etc.) in one move. Of course, thinking and interpreting sometimes occurs, but empathic understanding is different: I do not find myself interpreting your words and facial expression, but rather looking at you and seeing you immediately as sad. I can “see” the sadness in your face.

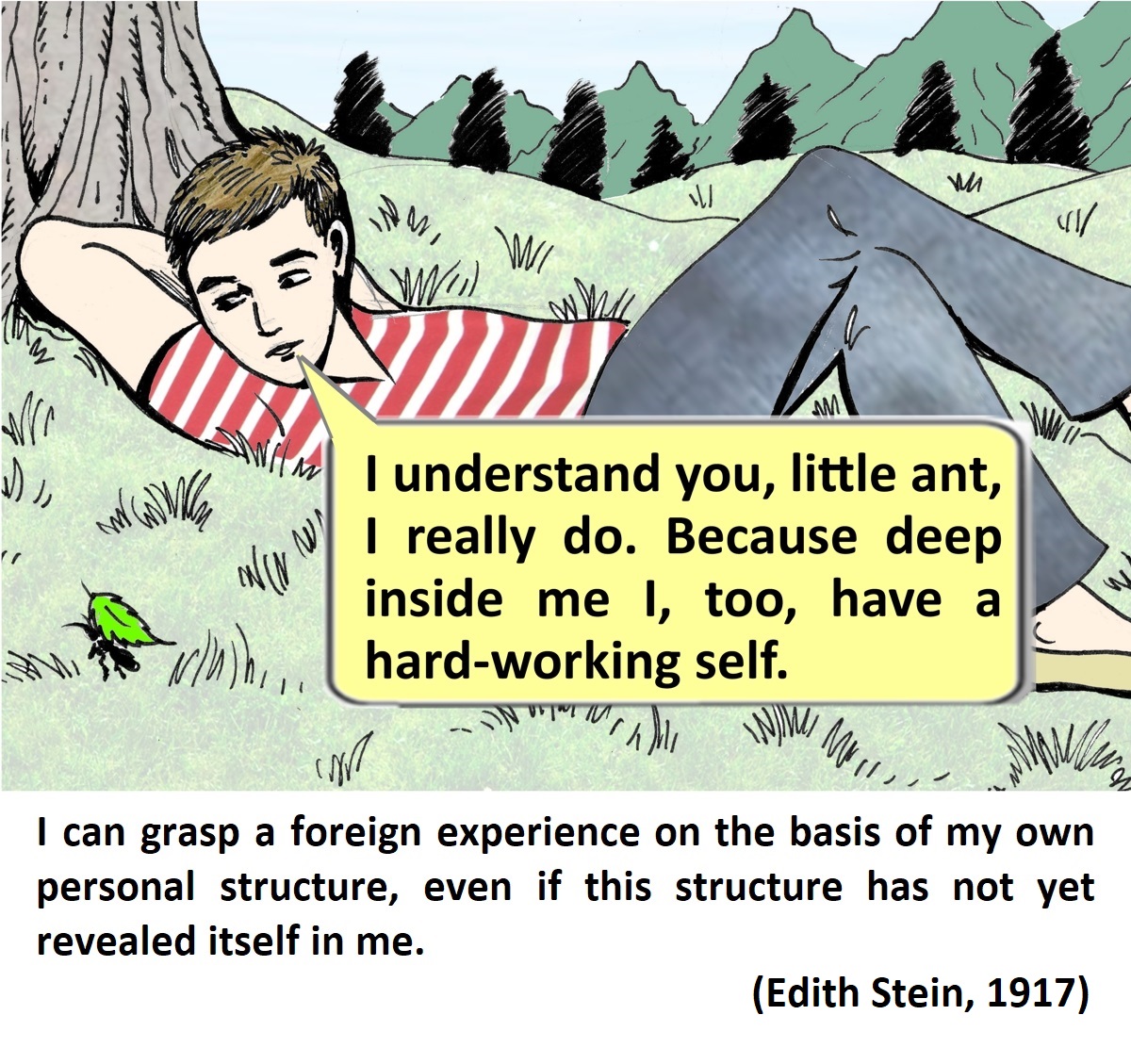

The following is adapted from the last sections of her book. Her complex language has been simplified a little for the sake of ease of reading. Here she argues that my ability to understand empathically another person depends on a similarity between us. I can comprehend another person only if I have similar experiential structures, at least as a dormant potential, even if they are still undeveloped in me.

From Section 7

I regard every person whom I can understand through empathy as a person whose experiences connect together into an intelligible, meaningful whole. It depends on my own experiential structure how much of his experiential structure I can grasp in my intuition. In principle, I can grasp all foreign experiences which can be derived from my own personal structure, even if my structure has not yet revealed itself in me. I can experience another person’s values through empathy and discover correlated levels in my own person, even though my own experience has not yet had an opportunity to reveal itself. For example, somebody who has never looked a danger in the face can still experience himself as brave or cowardly through the empathic presentation of another person's situation.

By contrast, I cannot grasp something that conflicts with my own experiential structure. But even then, I can still have it in my awareness as an empty presentation. For example, I can be skeptical about religion, and still understand that another person sacrifices all his earthly goods for the sake of his faith. I see him behave in a certain way, and I understand empathically that he has an experienced value which is the motive for his behavior. The experience that corresponds to his behavior is not accessible to me, causing me to ascribe to him a personal level which I do not myself possess. In this way l understand through empathy the type of person who is “homo religiosus,” who is by nature foreign to me, and I understand it even though what confronts me here will always remain unfulfilled in my experience.

To give another example, imagine that some people focus their lives entirely on buying material possessions, and everything else is secondary to them – something which I consider unimportant. In this case, I can see that the higher ranges of value that I can grasp are closed to them. And I can also understand these people, even though they are of a different type.

Now we can see why Dilthey said, “In the cultural sciences, the interpretation is done by the whole person.” Only somebody who experiences himself as a person, as a meaningful whole, can understand other persons. And we can also see why Ranke would like to "erase" his self in order to see things "as they were.” The “self” is the person’s experiential structure. Those who really know understand that the self is a source of deception, which threatens us with a danger: If we regard our own self as the standard for interpreting others, then we lock ourselves into the prison of our individuality. Others become riddles to us; or worse, we remodel them into our own image and so into a falsified truth.

From Section 8

We can also see, in what I said, how knowledge of a foreign personality is important for self-knowledge. We not only learn to make ourselves into objects [of understanding], as we saw earlier, but through empathy with people of similar natures – with persons who are of our type – what is “sleeping” in us is developed. Through empathy with personal structures that are composed differently from ours, we come to understand what we are not, and how we are more than others or less than others.

Thus, in addition to self-knowledge, empathic understanding is also an important aid to self-evaluation. Since the experience of value is basic to how we evaluate ourselves, when we understand through empathy new values, our own unfamiliar values become visible. When we empathically relate to values that are closed to us, we become conscious of our own deficiency or lack of value. Every comprehension of different persons can become the basis of our understanding of value. In the act of preference or disregard, we become aware of values in us that were unnoticed, and therefore we learn to asses ourselves correctly. We learn to see that we experience ourselves as having more or less value in comparison with others.

|

TOPIC 2: SHAPING MY BELIEF |

After working for a while with the influential philosopher Husserl, the father of phenomenology, Edith Stein resigned her post as his assistant. She was dissatisfied with Husserl’s approach, and decided to develop her own ideas, continuing her previous work in her doctoral thesis ON THE PROBLEM OF EMPATHY.

After working for a while with the influential philosopher Husserl, the father of phenomenology, Edith Stein resigned her post as his assistant. She was dissatisfied with Husserl’s approach, and decided to develop her own ideas, continuing her previous work in her doctoral thesis ON THE PROBLEM OF EMPATHY.

Phenomenology is the philosophical study of the inner landscape of human experience. It tries to describe the fundamental structure of the world as we experience it. To give a simple example, anything which I experience as a material object, appears to me as colored surfaces located in space. This is an essential structure of the experience of an object. In a similar manner, phenomenology investigates the essential structure of the experience of time, the experience of beauty, of love, etc.

Edith Stein was sympathetic to Husserl’s phenomenology, but she also disagreed with him. Unlike Husserl, she believed that you can analyze an experience only when you take into consideration other people around us and what they experience. An experience cannot be understood when isolated from the psychological and social context in which it occurs.

She therefore resigned from her work with Husserl, and devoted herself to writing several essays in line with this vision. Her work is phenomenological in the sense that it explores the structure of experience – but it also goes beyond a mere analysis of experiences, and examines the factors that shape them. In this way she was hoping to develop a philosophical foundation of psychology.

This is how we can understand her book Philosophy of Psychology and the Humanities, which she wrote in 1917, shortly after her separation from Husserl. Here she shows how our believing is not just a given fact in our experience, but is also shaped by our motivations and social context. In particular, we can willingly shape our beliefs by paying attention to certain things while ignoring others, by accepting certain interpretations and not others, and – as we can see in the text below – by embracing a belief or “neutralizing” it.

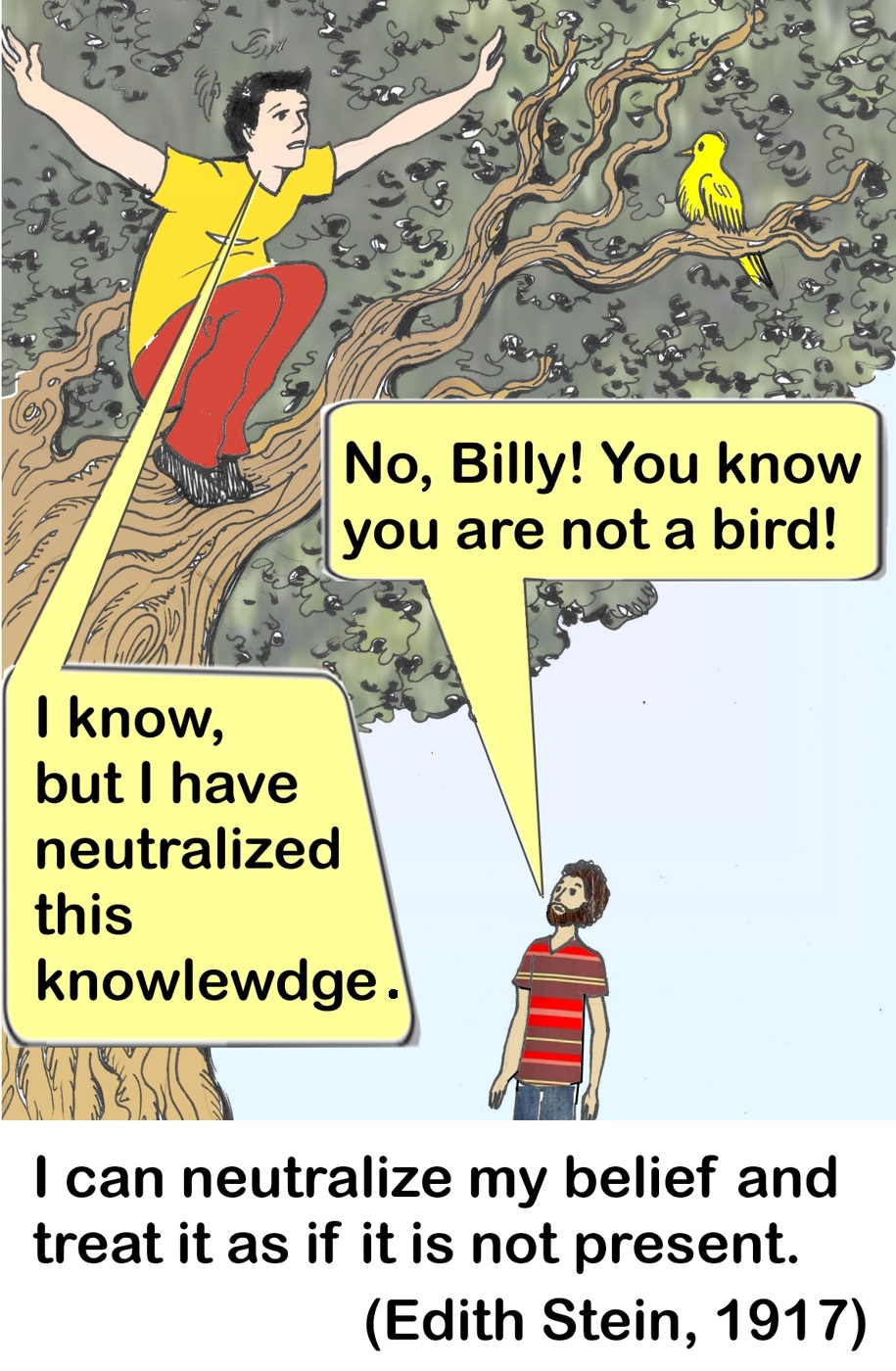

I can “take a stance” toward my belief. I can accept it, plant my feet upon it, and declare my loyalty to it. Or, I can place myself negatively against it. Suppose I accept it – this means that when it appears in me, I submit to it willingly, without reluctance. Suppose I deny it – this does not mean that I eliminate it.

Eliminating it is not under my control. In order to eliminate a belief I would need new reasons which would invalidate the reasons of the original belief. Nevertheless, I don’t have to acknowledge this belief. I can relate to it as though it is not present; I can make it inoperative. (This is what Husserl calls “epoché” – withholding judgement.)

For example, suppose I receive a message that will force me to take a trip. Later, I hear from an unreliable source that the event in question has already taken place, and my belief in this message immediately imposes itself on me. Yet, I “want” to not believe it as long as I have no confirmed report. I then comport myself just as I would if the belief was not present: I make no preparations, I do my usual daily tasks and so on, even though the belief is undeniably there in me.

As the following example shows, not only can I avoid making certain “free” actions, but moreover: I can make my beliefs inoperative, so that even my unfree behavior is discontinued. Suppose a mother hears from her son’s friends that he has died in the war. She is convinced that he is dead, but she “wants” to not believe in it, as long as she does not have the official report. As long as she withholds her assent to the belief, the sorrow that would develop from uninhibited belief does not awaken in her either.

[…] Or, suppose that a convinced atheist is drawn into a religious experience of God’s existence. He cannot escape the belief, but he does not plant his feet upon it, he does not allow it to become operative in himself, and he resolutely sticks with his “scientific worldview.”

Or, a last example: Suppose somebody arouses my affection, and I cannot prevent it. But I refuse to own up to it inwardly, and I withhold myself from it. This example is completely different from a case in which I struggle against a tendency that I don’t want to yield to. […] If I make my tendency inoperative, then not only do I refrain from the actions that it would motivate, but involuntary expressions of that tendency also stop by themselves and do not even appear.

[…]

The counterpart to denying a present attitude is adopting an attitude that is not present in me. I can plant my feet on a belief which I do not possess and which is not alive within me. For example, […] perhaps I decide to take a trip next year, to move to another city, to finish some work that I have begun, and so on, and I arrange my life entirely according to these future plans. However, deep down I am completely convinced that some event is going to intervene and cancel my plans. Yet, I deny my consent to this real live belief, and I do not let it become operative in me. Denying an attitude is always equivalent to adopting a stance opposed to it. And the latter, although it is not a genuine living stance, now determines my behavior.