|

AGORA - Philosophical Topics Important thinkers on important life-issues |

- Attitudes

- Authenticity

- Death

- Philosophizing

- Friendship

- Beauty

- Happiness

- Inner Freedom

- Inner Truth

- Love

- Meaning

- Music

- Right & Wrong

- Romantic Love

- Sex

- Solitude

- Sublime

- The Other Person

This month's topic: ATTITUDES TO LIFE

How should I relate to life?

WEEK 1 - Marcel WEEK 2 - Kierkegaard WEEK 3 - Seneca WEEK 4 - Nietzsche An issue for reflection

HOW SHOULD I RELATE TO LIFE?

- I love my smartphone, my television, my GPS.

-

That’s too much noise for me. I prefer a quiet time with myself or with a friend. - What about new Hollywood movies? New video-games? Facebook?

- I don’t need them. They are shallow distractions, popular trash.

- You want everything to be deep and meaningful.

- And you?

- I just like fun. If I can make somebody smile, what else do I need?

- I am interested in people too. - Yes, but in a different way. You want to have “deep conversations” with them. I like to have good time with people, to do things together.

- In short, you and I you face life differently.

- I stand here, on earth, together with everything around me. You, on the other hand, look high up to the sky above.

- In other words, we have two very different attitudes to life.

- How many attitudes are there?

GABRIEL MARCEL

Observing life versus being a witness to life

Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973) was a French existentialist philosopher, playwright, pianist and music critic, who wrote about the human condition in the modern world. He studied philosophy, under Henri Bergson and others at the University of Paris and the Sorbonne. He grew up an atheist, but converted to Catholicism at the age of 40, and his writings have a vaguely spiritual orientation. Although he is regarded as an existentialist, his philosophy is very different from that of Sartre, whom he often criticized. Unlike Sartre’s empty and lonely world, Marcel’s world has the possibility of true togetherness, hope, and meaning. His philosophical writings are not easy to read – they are usually like musical themes developing in complex ways, rather than a linear theory.

Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973) was a French existentialist philosopher, playwright, pianist and music critic, who wrote about the human condition in the modern world. He studied philosophy, under Henri Bergson and others at the University of Paris and the Sorbonne. He grew up an atheist, but converted to Catholicism at the age of 40, and his writings have a vaguely spiritual orientation. Although he is regarded as an existentialist, his philosophy is very different from that of Sartre, whom he often criticized. Unlike Sartre’s empty and lonely world, Marcel’s world has the possibility of true togetherness, hope, and meaning. His philosophical writings are not easy to read – they are usually like musical themes developing in complex ways, rather than a linear theory.

The following text is adapted from Marcel’s essay “Testimony and Existentialism” (1946), which appeared in English in his short book The Philosophy of Existentialism. Marcel distinguishes here between two different attitudes to life: observation and testimony. As an observer, I look at life from the outside, like objective facts that I note and manipulate, without personal involvement and commitment, without giving myself to anything. In contrast, as a witness I regard life as calling me to respond in a personal, creative, committed way. Marcel calls this attitude “testimony” because it is what I do in court when I decide to testify truthfully about something that I saw, even if this puts me in danger, even if the court is corrupt. Similarly, I am a witness when I freely commit myself to a certain value despite all difficulties and dangers, when I am a faithful witness to a “light” which touches me. In this sense, life for me is a “gift” which I am called to accept freely, faithfully, personally, creatively.

I will examine first the distinction between testimony and observation.

What is an observation? I observe something which is outside myself, and which I notice. I cannot help noticing it – I am forced to notice. At the same time, my observation does not change the thing I have observed. Moreover, the “I” who observes it is very impersonal: the same observation could have been made equally well by anyone in my place.[…]

Now let us turn to testimony. It is never, and cannot ever be SOMEBODY who bears it. It is always and necessarily “I” – and if not I myself then somebody else who is another “I.” It is always an individual self, with his individual identity […] I can testify [in court] that John Smith was at the corner of Regent Street yesterday at 4 p.m., he was bare-headed, his expression was tired, etc. I said that I CAN testify – this means that “I am in a position to…” It can also mean that “I have the right.” And in certain situations I have to say that I MUST bear witness.

[…]

This brings us to the distinction between the observer and the witness, and a little reflection will show us that it is a distinction between two opposite metaphysical attitudes.

[…]

It happened to all of us to say about some devoted life that such a life is a testimony. Now, clearly, the value of such testimony is connected with some form of faithfulness which is embodied in such kind of life. It may be the faithfulness of a child to her parents, of a servant to his employer, or it may be faithfulness to a cause served until the end. The notion of faithfulness can be degraded into passive submission, into a mindless habit; clearly, this has no value. It is valuable when we follow faithfully, through darkness, a light which has guided us, and which is no longer visible to us directly. Indeed, it can be said that testimony is possible because there is a darkness, an eclipse.

[…]

We are now in a position to see that testimony is based on faithfulness to a light. In using this term I want to exclude its religious connotation, and to treat it simply as signifying a gift. The point is that testimony is about something which has been received.

[…]

To receive in this sense is an act, and even an art, like a host who brings out the best part of his guest, and creates sincere communication and exchange. This is what we must keep in mind when we analyze the term “gift.” To give is to give to somebody. Only a somebody can give to another somebody, and this implies some form of self-gift. Even if I give a thing, if I really give it, it must be something of myself.

[…]

The gift, for the person who receives it, is not just one more thing added to his possession – it exists in another dimension, the dimension of testimony, since it is an indicator of friendship or of love. But it exists in this dimension only if it is recognized as existing in this way. In this sense, it is like an appeal which demands a certain response. Think of a small child who brings you three messy flowers he has picked by the side of the road. He expects you to admire them. He awaits from you a recognition of the value of the gift. And if you lose the flowers, or put them down carelessly, or do not interrupt your conversation in order to express your delight, you are guilty of a sin against love.

[…]

Aren’t there ungrateful people who are unable to respond to life, just as there are others who are unable to trust, and who are therefore unable to recognize that life is a gift and that all things are given to them?

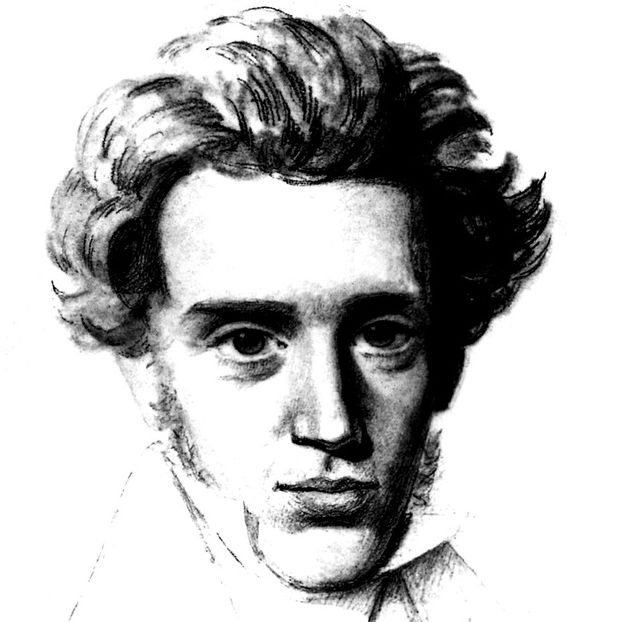

SØREN KIERKEGAARD

The aesthetic versus the ethical

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) was a Danish philosopher who is regarded as one of the two “fathers” of existentialism (the other one being Friedrich Nietzsche). He was born in Copenhagen to a wealthy family and lived there most of his life in relative loneliness. He was once engaged to marry, but after several months broke his engagement (and the woman quickly married somebody else). His criticism of society and organized religion angered many people and alienated them. He died in a hospital from medical complications at the age of 42. His works became famous only in the 1920s, and they have been very influential ever since.

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) was a Danish philosopher who is regarded as one of the two “fathers” of existentialism (the other one being Friedrich Nietzsche). He was born in Copenhagen to a wealthy family and lived there most of his life in relative loneliness. He was once engaged to marry, but after several months broke his engagement (and the woman quickly married somebody else). His criticism of society and organized religion angered many people and alienated them. He died in a hospital from medical complications at the age of 42. His works became famous only in the 1920s, and they have been very influential ever since.

Kierkegaard’s extensive writings revolve primarily around the issue of how to live truly or authentically (or how to be a Christian, as he sometimes phrases it). For him, truth is subjective, and truly living means living with one’s entire being, with passion and commitment and faith. Most people, however, live a dull life of self-deception, so they do not really live.

The following text is adapted from Part 1 of Kierkegaard’s famous book Either/Or (1843). As in many of his books, Kierkegaard does not present one unitary theory. Rather, the book expresses several different voices, each one written by a different imaginary writer, sometimes in the form of letters, sometimes in the form of a personal diary, a poem, etc. In this way Kierkegaard presents to the readers several different perspectives on life, and he encourages them to find themselves in them.

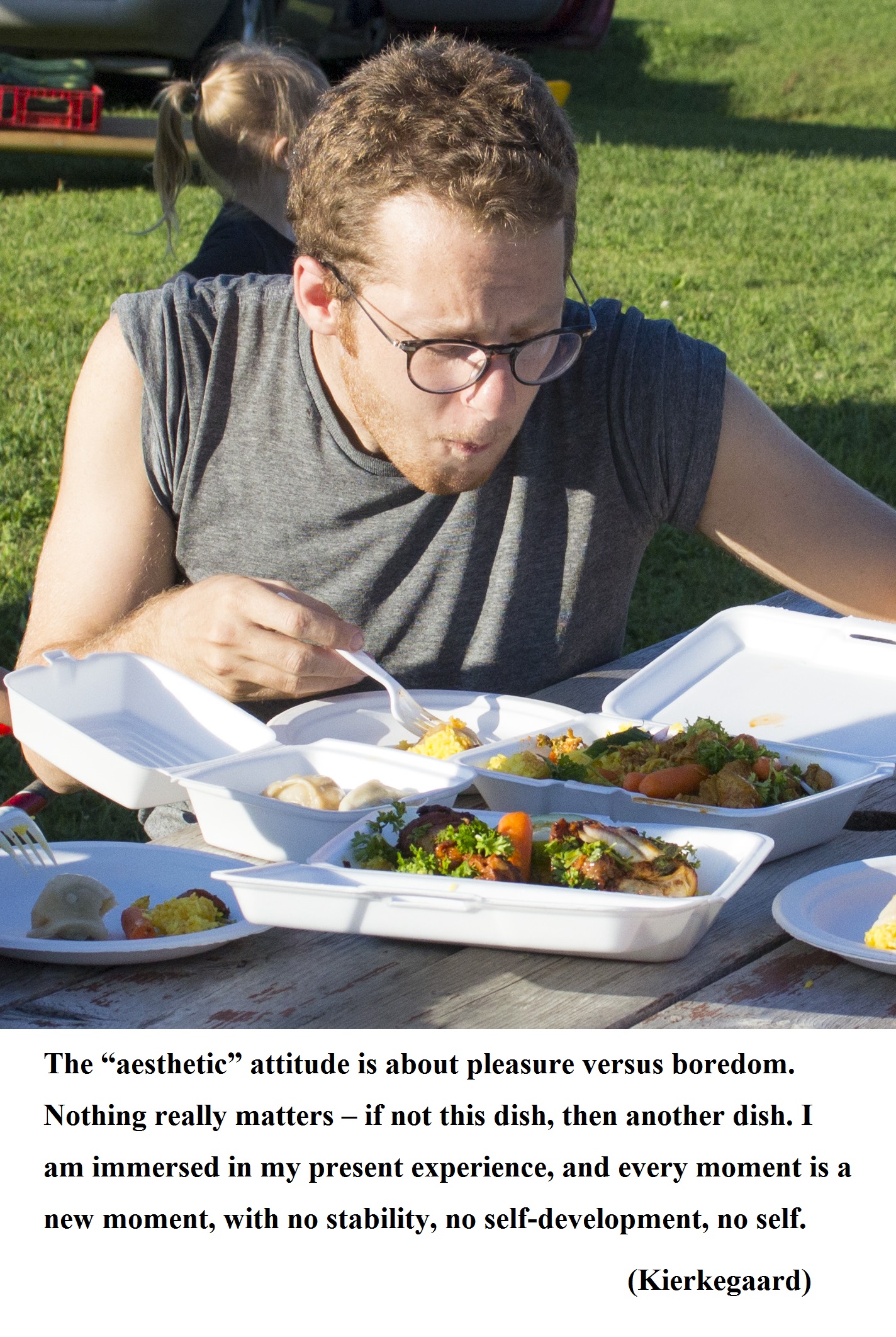

The fragments that compose Either/Or describe two main attitudes to life, the aesthetic and the ethical. (Later Kierkegaard would add a third, religious attitude.) In the aesthetic attitude I immerse myself in immediate experience, and my life revolves around INTERESTING (fun, pleasure) versus BORING. Therefore, the aesthetic life is a collection of moments of pleasure or interest, in which nothing really matters (If not this woman, then the next woman). It has no long-term project, no self-development, no stable self.

The alternative attitude, the ethical, is based on decision and commitment. It revolves around GOOD versus EVIL, and it consists of long-term commitments and projects, self-development and self-creation.

The following text is written by the imaginary “Judge William” who looks at life from the ethical perspective. He is writing to another imaginary person, a young romantic man called “A” who lives an aesthetic life.

There are people who are too degenerate to understand such a dilemma, and their personalities lack the energy to say “Either/or” with pathos. This phrase has always made a deep impression on me, and it still does. […] And you – this phrase is often on your lips. It has almost become a slogan for you. What significance does it have for you? None at all. You, according to what you say, regard it as a wink of the eye, a snap of the fingers, a coup de main, an abracadabra. […] You take great delight in “comforting” people when they are in critical situations. You listen to their story and say, “Yes, I see that there are two possibilities – you can either do this or do that. My sincere opinion and my friendly counsel is this: Do it or don’t do it – you will regret both.” But he who mocks others mocks himself, and your response is a profound mockery of yourself, a sorry proof of how limp your soul is.”

[…]

Your choice is an aesthetic choice, but an aesthetic choice is no choice. The act of choosing is essentially an expression of the ethical. Whenever there is a question of either/or in the strict sense, you can always be sure that the ethical is involved. The only absolute either/or is the choice between good and evil, and this is the ethical. The aesthetic choice is either entirely a matter of immediate experience, or it loses itself in the many. Thus, when a young girl follows the choice of her heart, her choice, however beautiful it may be, is strictly speaking no choice, since it comes entirely from immediate experience [the feeling of love]. When a man deliberates aesthetically on life’s problems, as you did, he does not get ONE either/or but many, because when he does not choose absolutely he chooses only for the moment, and therefore he can choose something different the next moment.

The ethical choice is in a certain sense much easier, much simpler, but in another sense it is infinitely harder. A person who defines his life-task ethically usually doesn’t have a large selection to choose from. But on the other hand, the choice has a much greater importance for him. Making a choice is not so much a question of choosing the right but a matter of the energy, the seriousness, the pathos with which one chooses. In this way the personality announces its inner infinity, and thus the personality is consolidated. […] Since he made the choice with his entire inner being, his nature is purified and he relates directly to the eternal power whose omnipresence interprets the whole of existence. This higher consecration is never achieved by somebody who chooses aesthetically. The rhythm in his soul, despite its passion, is a spiritu levis. Perhaps you will succeed to accomplish much in life, perhaps you will even astonish the world, and yet you will miss the highest thing, the only thing which is truly significant – perhaps you will gain the whole world and lose your own self.

So you have to either live aesthetically or live ethically. In these two alternatives there is not yet a question of choice, strictly speaking. Because a person who lives aesthetically does not choose.

[…]

My either/or is not primarily about the choice between good and evil. It is about the choice between good-and-evil and excluding them. It is the question about the coordinates through which you would live and relate to existence. It is true that the person who has chosen good-and-evil chooses good, but this becomes evident afterwards. Because the aesthetic is not the evil but neutrality, and this is why the ethical constitutes the choice. The question is not, therefore, choosing between willing the good OR willing the evil, but rather choosing to WILL. And this choice posits the good and the evil.

SENECA

Don't be a slave to Fortune!

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (Seneca the Younger) (4 BC – 65 AD) was a Roman Stoic philosopher, politician, and writer. He was born in Spain to a Roman nobleman. As a child he came to Rome and was trained in languages, rhetoric, and philosophy. His earlier political career was modest, and at the age of 41 he was exiled to Corsica by the emperor Claudius, probably for adultery with a noble woman. At the age of 49 he returned to Rome, where he became a tutor of young Nero, and later an advisor and speech writer of Nero the emperor. At the age of 68 he was accused of conspiracy and sentenced by Nero to commit suicide. Seneca was reported to react calmly, cutting his wrists and legs, but to no avail. He tried taking hemlock, which also failed. He was finally placed in a bath, where he suffocated from the steam.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (Seneca the Younger) (4 BC – 65 AD) was a Roman Stoic philosopher, politician, and writer. He was born in Spain to a Roman nobleman. As a child he came to Rome and was trained in languages, rhetoric, and philosophy. His earlier political career was modest, and at the age of 41 he was exiled to Corsica by the emperor Claudius, probably for adultery with a noble woman. At the age of 49 he returned to Rome, where he became a tutor of young Nero, and later an advisor and speech writer of Nero the emperor. At the age of 68 he was accused of conspiracy and sentenced by Nero to commit suicide. Seneca was reported to react calmly, cutting his wrists and legs, but to no avail. He tried taking hemlock, which also failed. He was finally placed in a bath, where he suffocated from the steam.

The following text is adopted from Seneca’s book On the Happy Life (58). Seneca wrote more than ten books and 124 philosophical letters, all in the spirit of Stoicism. As a Stoic, he suggested that we should face life with self-control and inner peace, doing our duties and developing our virtues in accordance with nature and reason. A central theme in Seneca’s book is: Don’t be a slave to fortune, whether good fortune or bad fortune. Welcome pleasure and riches when they come – but don’t depend on them. Avoid pain and misfortune – but don’t be devastated by them.

From BOOK 12

The pleasures of wise people are mild, well-behaved, almost dull. They are kept under restraint and are barely noticeable. The wise do not invite pleasures to come, and do not receive them with honor or delight when they come by themselves. They do not mix them up with their lives and fill up empty spaces with them, like an amusing farce in the intervals between serious business.

From BOOK 20

I will look upon death or upon a comedy with the same facial expression. […] I will despise riches when I have them just as when I don’t have them. If those riches are elsewhere I will not be more gloomy, and if they shine around me I will not be happier than without them. Whether Fortune comes or goes, I will not pay attention to her. I will regard all lands as if they belong to me, and my possessions as if they belong to all humankind. I will live remembering that I was born for others, and I will thank Nature for this. Because how could she have done better for me? She has given me to everybody and everybody to me.

Whatever I may possess, I will not collect it greedily and not waste it carelessly. I will think that none of my possessions is as real as what I have given away to people who deserve it. […] When eating and drinking, my purpose will be to satisfy the desires of Nature, not to fill and empty my belly. I will be pleasant to my friends, gentle and mild to my enemies. I will pardon before I am asked for it, and I will meet half way the wishes of honorable people. […] Whenever Nature demands my breath again, or reason asks me to get rid of it, I will quit my life, and I will call everybody to witness that I have loved a good conscience and good pursuits, and that nobody’s freedom (especially my own) has suffered because of me.

From BOOK 25

Make me the master in the house of a very rich man, place me where gold and silver are used for the simplest purposes – I will not think more about myself because of such things which are not part of me (even though they are in my house). Put me among the beggars – I will not despise myself for sitting among those who hold out their hands for money. Because what can the lack of a piece of bread matter to somebody who doesn’t lack the power to die?

I prefer a magnificent house to the beggar's shelter, but place me among magnificent furniture and luxury – I will not think myself happier because my coat is soft, or because my guests rest on purple. Now, change the scene – I will not be more miserable if my tired head rests on a bundle of straw, or if I lie on a cushion from the circus with all the stuffing coming out through the patches in the cloth. I prefer, as far as my feelings go, to show myself in public dressed in nice robes of office, rather than with naked or half-covered shoulders. I would like every daily task to turn out just as I wish, and to constantly receive new congratulations one after the other – nevertheless I will not pride myself on this.

[…]

I would rather be a conqueror than a captive. I despise the power of Fortune. Nevertheless, if I could choose, I would choose its better parts. I will make whatever happens to me become a good thing.

NIETZSCHE

The passionate creative loner

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) was a German philosopher and one of the most influential thinkers in modern times. He studied theology and classical philology at the University of Berlin, but apparently lost his faith and continued with philology. At the age of 24 he became a professor of philology at the University of Basel (even though he had not yet written his doctoral thesis). He left briefly to serve as a medical assistant in the Prussian army, returned to continue teaching, and for several years was influenced by the compositor Wagner. His health started declining, and at the age of 34 he retired with a modest pension. This enabled him to write productively, and to move from place to place. In 1899, in Turin, Italy, he collapsed and suffered mental and physical breakdown. For the rest of his life he remained under the care of his mother and sister.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) was a German philosopher and one of the most influential thinkers in modern times. He studied theology and classical philology at the University of Berlin, but apparently lost his faith and continued with philology. At the age of 24 he became a professor of philology at the University of Basel (even though he had not yet written his doctoral thesis). He left briefly to serve as a medical assistant in the Prussian army, returned to continue teaching, and for several years was influenced by the compositor Wagner. His health started declining, and at the age of 34 he retired with a modest pension. This enabled him to write productively, and to move from place to place. In 1899, in Turin, Italy, he collapsed and suffered mental and physical breakdown. For the rest of his life he remained under the care of his mother and sister.

Nietzsche’s vision of how to relate to life is best expressed in his idea of the “overman.” The overman is a person who overcomes his small self, rejects authority and group-mentality, and lives fully, passionately, and freely in the light of his self-created values. The following three passages express different aspects of Nietzsche’s “overman.”

The first passage, “Will and Wave” from The Gay Science (a book in which the term “overman” does not yet appear), uses the image of waves as a metaphor for a passionate life that is driven by the power of the will.

The second passage, “Excelsior,” from the same book, describes the challenge of living as a free individual who rejects authority, especially religion’s promises of truth, peace, and happiness.

The third passage, “On the famous wise men” from Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” applies the same vision to intellectuals. Here Nietzsche laughs at “the wise men” – academic intellectuals who follow accepted ideas. He contrasts them with individuals who have intellectual passion and the courage to create their own ideas.

WILL AND WAVE (from The Gay Science, 310)

How greedily this wave approaches, as if there was some goal to be reached! How, with awesome enthusiasm, it crawls into the deepest cracks of the rocky cliff! It seems that it wants to anticipate somebody. It seems that something is hidden there, something of value, high value.

And now the wave comes back, a little more slowly, still quite white with excitement – is it disappointed? But another wave is already approaching, greedier and wilder than the first, and its soul, too, seems to be full of secrets and the desire to dig up treasures. This is how the waves live. This is how we, who desire, live. More I will not say.[…]

Raise your dangerous green bodies as high as you can! Make a wall between me and the sun, just as you do now! Indeed, nothing is now left of the world except for green dusk and green flashes of lightning. Continue as you please, you jokers, roar with delight or malice – or dive again, pour your emeralds into the deepest depths, and spread over them your endless white foam. […] Because – listen well – I know you and your secrets. I know your kind! You and I, aren’t we of the same kind? You and I, don’t we have the same secret?

EXCELSIOR! (from The Gay Science, 285)

You will never pray again, never adore again, never again rest in endless trust. You don’t allow yourself to stop before ultimate wisdom, ultimate goodness, ultimate power, and you liberate your thoughts. You have no permanent protector and friend for your seven solitudes […] There is no reason any more in what happens, no love in what will happen to you. No resting place is open to your heart anymore, where it could find and no longer to seek. You resist any ultimate peace, you want the eternal cycle of war and peace.

Man of renunciation, do you want to renounce all this? Who will give you the necessary strength? Nobody yet has had this strength.

OF THE FAMOUS WISE MEN (from Thus Spoke Zarathustra)

I regard as “truthful” a person who goes into godless deserts, after he has broken his admiring heart. In the yellow sands, burned by the sun, he glances with thirst at the oases that are full of water-wells, where living beings rest under dark trees. Yet, his thirst does not convince him to become like them and to live in comfort, because where there is an oasis there are also idols.

Hungry, violent, lonely, godless – this is how his lion-will wants to be. Free from the happiness of slaves, saved from gods and adorations, fearless and fear-inspiring, great and lonely – such is the will of the truthful.

[…]

You are not eagles, therefore you have never experienced the happiness which is in the terror of the spirit. And somebody who is not a bird should not build his nest over the abyss.

You are lukewarm to me, neither cold nor warm. But all profound knowledge flows cold. Ice-cold are the inner wells of the spirit, refreshing for hot hands and for men of action. You stand there honorable and rigid and with straight backs, you famous wise men. No strong wind will move you.

Have you never seen a sail go over the sea, rounded and tight and trembling with the violence of the wind? Like the sail, trembling with the violence of the spirit, my wisdom goes over the sea – my wild wisdom.

But you, servants of the people, you famous wise men – how could you go with me?

Thus spoke Zarathustra.

- Authenticity