|

AGORA - Philosophical Topics Important thinkers on important life-issues |

- Attitudes

- Authenticity

- Death

- Philosophizing

- Friendship

- Beauty

- Happiness

- Inner Freedom

- Inner Truth

- Love

- Meaning

- Music

- Right & Wrong

- Romantic Love

- Sex

- Solitude

An issue for reflection

WHAT CAN WE POSSIBLY SAY ABOUT THE SUBLIME?- This concert was simply … simply … simply … beyond words.

- You mean the music was pretty?

- No, no. “Pretty” is too cute: a pretty flower, a pretty face. It was grand, vast, like the ocean.

- Whatever the word, you enjoyed it, right?

- “Enjoyed?” No, that sounds too pleasant, too lovely. I was overwhelmed, like in the middle of an awesome thunder storm!

- So you left the concert in the middle?

- On the contrary. I was glued to my chair with an open mouth. I was transported to a higher world.

- Well, well. Beyond words, like a vast ocean, like an overwhelming thunderstorm, like a higher world. Do you mean that it was sublime?

- Yes, SUBLIME, that’s the word I was looking for! The word beyond words.

- But isn’t “sublime” the same as “very beautiful”?

- No, no, sublime means … well, it means … I guess we need some good philosopher to tell us.

The Sublime is higher than Nature

Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) was a major German playwright, as well as a poet and a philosopher. At an early age he started writing theatrical plays, and eventually became one of the most important German playwrights of modern times. As a young man he studied medicine and became a military doctor in Stuttgart, but did not like this position and escaped to Weimar. He became a professor of philosophy and history at nearby Jena. Together with Goethe, he founded the influential Weimer Theater. He died at the age of 45 from tuberculosis.

Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) was a major German playwright, as well as a poet and a philosopher. At an early age he started writing theatrical plays, and eventually became one of the most important German playwrights of modern times. As a young man he studied medicine and became a military doctor in Stuttgart, but did not like this position and escaped to Weimar. He became a professor of philosophy and history at nearby Jena. Together with Goethe, he founded the influential Weimer Theater. He died at the age of 45 from tuberculosis. Schiller’s philosophical work is primarily about ethics, aesthetics, art, poetry, and human freedom, and he often develops in his own ways ideas from Immanuel Kant. The following text is adapted from his essay ON THE SUBLIME (1801). Here he discusses the experience of the sublime, which we experience when we encounter something grand that inspires admiration and awe: a tremendous thunder-storm, a desolate mountain over a terrifying abyss, an awe-inspiring symphony, etc.

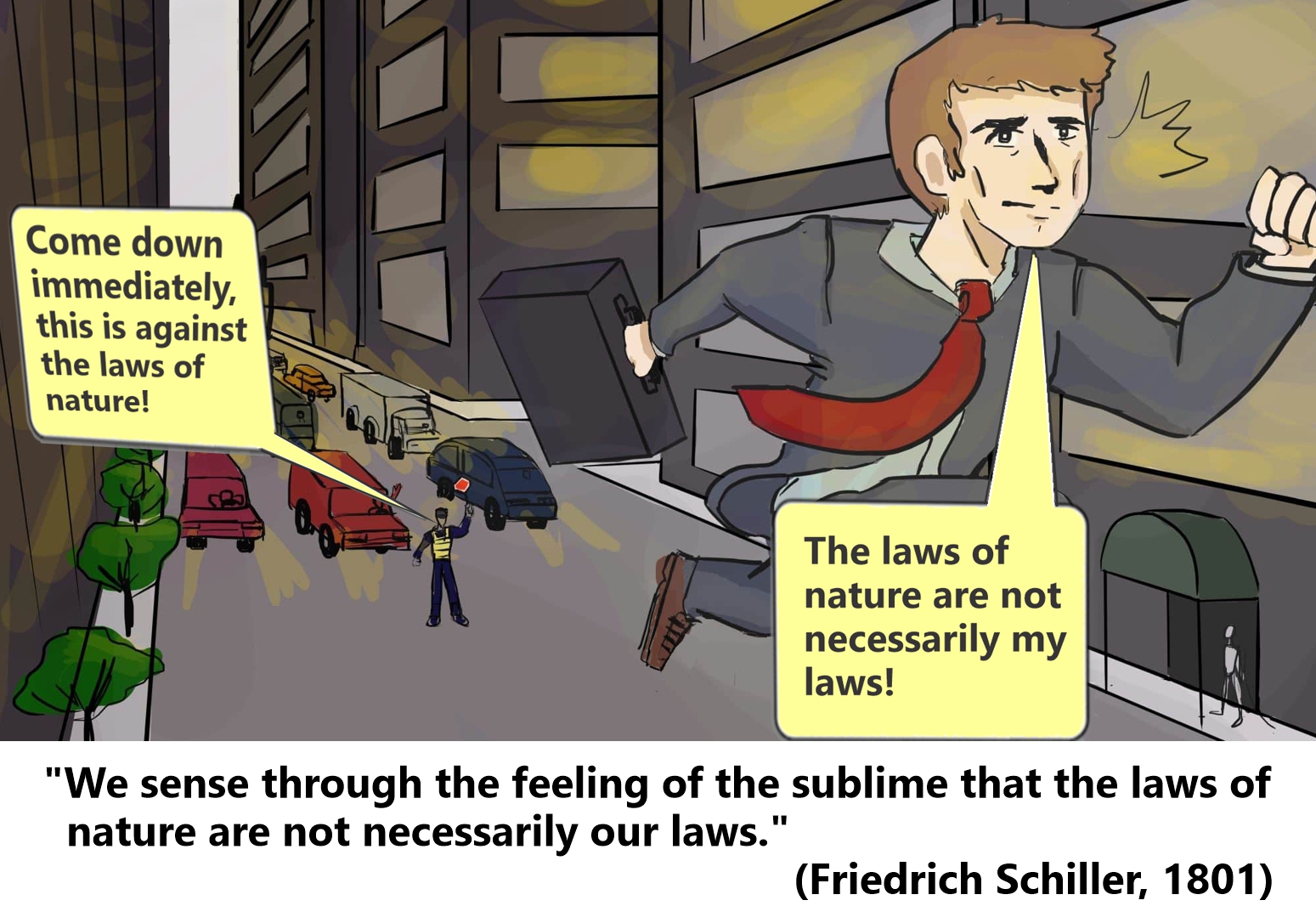

Schiller explains the experience of the sublime by comparing it to the experience of beauty. Beauty is pleasant, while the sublime produces in us awe and even anxiety. Beauty is limited to the sensuous qualities that follow harmony and order, while the sublime takes us beyond order and reason. Beauty is in the natural world, while the sublime rises beyond it. The sublime, therefore, reminds us of a power within us that goes beyond the laws of nature, namely our own free will.

There are two capacities which nature gave us as companions throughout life. The one, friendly and lovely, shortens the troubles of our journey with its pleasant plays. It makes the chains of necessity less heavy for us, and it leads us with joy and laughter to the most dangerous places, where we must act as pure spirits and strip ourselves of everything that is of the body, as when we think of truth or perform our duty. Once we are there, beauty abandons us, because its domain is only the world of the senses, and its earthly wings cannot carry it beyond that world. But now the second capacity enters the stage, solemn and silent, and with a resolute arm it carries us over the dizzying depth.

In the first of these capacities we recognize the feeling of the beautiful, in the second – the feeling of the sublime. The beautiful is already an expression of freedom, but not the freedom that elevates us above the power of nature and releases us from bodily influences. It is, rather, the freedom which we enjoy within nature as human beings. With beauty we feel ourselves free because our senses are in harmony with the laws of reason. With the sublime we feel ourselves free because our senses have no influence on the authority of reason, because the spirit acts as if it obeys only its own laws.

The feeling of the sublime is a mixed feeling. It is a combination of anxiety – which at the extreme expresses itself as a shudder – and of joy, which can rise to ecstasy. And although it is not precisely pleasure, yet delicate souls generally prefer it to every pleasure. […] We therefore sense through the feeling of the sublime that our spiritual nature is not necessarily determined by the state of our senses; that the laws of nature are not necessarily our own laws; and that we have in us an autonomous principle, independent of all sensuous feelings.

A sublime object can be considered from two perspectives. Either we present the sublime object to our understanding – and then we fail to form any image or a concept of it; or we compare the sublime object to our own vital power, and we find that in front of it, our own power is nothing. But although in both of these cases we experience the painful feeling of our own limitation, yet we do not try to avoid the sublime object, but rather we are attracted to it with an irresistible force. Could this possibly happen if the limits of our [sensuous] imagination were the same as the limits of our understanding? Why would we want to remember the omnipotent forces of nature, unless we had within us something that cannot be a victim of these forces?

[…] But nature in all of its infinity cannot reach the absolute greatness which is in ourselves. We submit willingly to the physical necessity of our well-being and our existence, because that power reminds us that there are in us principles that escape its empire. Man is in the hands of nature, but the will of man is in his own hands.

Nature used our senses to teach us that we are something more than mere sensuous nature. It even uses sensations to lead us to the discovery that we are by no means slaves to the violence of the sensations. And this is an entirely different effect from the effect that can be produced by the beautiful.

[…]

As long as man was a slave of physical necessity – when he found no way to escape the narrow circle of his bodily needs, and before he found the liberty that connects him with the angles – nature’s incomprehensibility reminded him of the limits of his imagination, and nature’s destructiveness reminded him of his physical weakness. He was forced to pass fearfully towards the first, and to run away with fear from the second. But once free contemplation assured him against the blind forces of nature, and once he discovered in this flood of phenomena something permanent in his own being, then immediately the many harsh things of nature around him begin to speak in another language to his heart. And the grandeur outside him is the mirror in which he finds the absolute greatness which is in himself. He approaches fearlessly and with excited pleasure those images which once terrified his imagination. And he intentionally focuses the strength of that faculty which represents the infinite when perceived by the senses, in order to feel more vividly how much these ideas in him are superior to what all that the sensuous faculty can give.

The sight of a distant infinity – of heights beyond calculation, the vast ocean at his feet, and the greater ocean that stretches above his head, elevate his mind beyond the narrow circle of the real, beyond this narrow and oppressive prison of physical life. The simple majesty of nature offers him a less limited measure for estimating its grandeur. Surrounded by the great shapes which it presents to him, he can no longer bear anything small in his way of thinking. Who can tell how many brilliant ideas, how many heroic decisions – which would have never been born in the scientist’s dark office, nor in the saloons where society people elbow each other – have been inspired suddenly during a walk, only through the soul’s contact with, and struggle with the great spirit of nature?

The Sublime Style

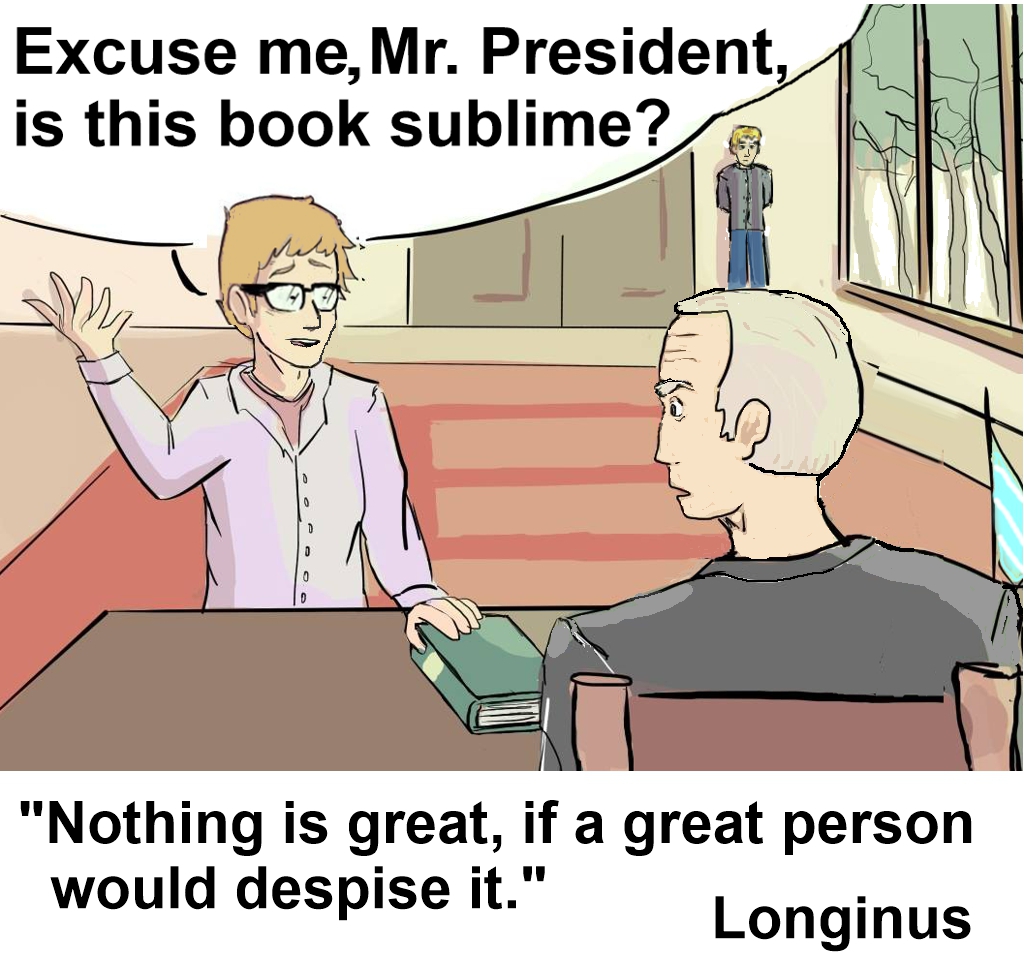

Longinus, who probably lived somewhere in the Roman Empire in the first century AD, was the first known thinker to analyze the concept of the sublime. Nothing is known about his life, and even the name “Longinus” is questionable. The passages below are adopted from his book THE SUBLIME. The book, written like a letter to a friend, explains that the sublime is produced only in language, in other words it appears in written or spoken speech (as opposed to modern thinkers who found the sublime also in nature, in art, and in people). A speech is sublime when it amazes the listeners and elevates their minds to a kind of ecstasy. This happens when it is higher than ordinary speech, but is also simple and direct, without pretensions, tricks, and childishness.

Longinus, who probably lived somewhere in the Roman Empire in the first century AD, was the first known thinker to analyze the concept of the sublime. Nothing is known about his life, and even the name “Longinus” is questionable. The passages below are adopted from his book THE SUBLIME. The book, written like a letter to a friend, explains that the sublime is produced only in language, in other words it appears in written or spoken speech (as opposed to modern thinkers who found the sublime also in nature, in art, and in people). A speech is sublime when it amazes the listeners and elevates their minds to a kind of ecstasy. This happens when it is higher than ordinary speech, but is also simple and direct, without pretensions, tricks, and childishness. A great mind is required to recognize and produce the sublime. Thus, sublime speech comes out a person of a great mind or spirit. Therefore, if we seek the sublime we must cultivate the greatness of our mind.

CHAPTER I

Sublimity is always an eminence and excellence in language. And from this, and only this, the greatest poets and prose-writers have achieved the first place, and have clothed their fame with immortality.

Because speeches of extraordinary genius lead the hearer not to persuasion but to ecstasy. The marvelous, with its power to amaze, is always necessarily stronger than the attempt to persuade and to please. To be persuaded usually depends upon us the hearers, while genius has a force that is irresistible by any hearer, and it stands high above him. One’s creative skill, and power of organization, are seen not in one or two passages, but emerge out of the whole context. As we know, when sublimity appears at the right moment, it parts all the matter this way and that way, and like a flash of lightning it reveals the power of the orator, at a stroke and in its entirety.

CHAPTER VII

As in our ordinary life, nothing is great if a great person would despise it. Thus, wealth, status, honor, kingdoms, and similar things that are often praised so arrogantly, could never appear to be a superior good, at least to a sensible person, since it is a good thing to feel contempt for them. Certainly, many people admire these things – especially those who hope to have them more than those who actually have them, but a great soul would let them go. This is also the case with things that are elevated in writings of poetry and prose. When something appears to have the greatness to which people attach so much careless praise, we have to ask ourselves whether, upon a careful examination, this apparent greatness could turn out to be vain and hollow, and something which it is nobler to despise than to admire. Because it is a fact of nature that the soul is raised by true sublimity, that it gains a proud step upwards, it is filled with joy and exultation, as though it had produced by itself what it hears.

Therefore, whenever a person of reason and literary experience hears something that does not turn his mind to high thoughts, and that does not leave in his mind material for fresh reflection beyond what is actually said, and if the effect disappears when he looks carefully at the whole context, this can never be true sublimity, because its effect remains only as long as it is heard. What is really great gives much food for fresh reflection, which it is hard to resist, even impossible, and it creates a strong and permanent memory. You can be sure that the beautiful and genuine effects of sublimity please always, and please everybody. Because when people of different habits, lives, ambitions, ages, all have the same view about the same writings, the judgement of such different individuals gives a powerful testimony for what they admire, beyond all dispute.

CHAPTER IX

Great natural genius [=talent] is more important than any other element [of sublimity]. Therefore, even if this genius is a gift rather than something we acquire, yet as much as possible we must nurture our souls to everything that is great, and make them full of noble gifts. You might ask: How? I myself have written in another place: “Sublimity is the sound which comes out of a great mind.” This is how an idea, without any speech, unclothed and unsupported [by any literary style], often inspires our wonder, because the thought itself is great: The silence of Ajax in the Book of the Underworld is great and more sublime than any words.

First, then, it is necessary to acknowledge the source from which sublimity comes: The true orator must not have a low mean spirit, because it is not possible that somebody who thinks small thoughts, and practices them all his daily life, could express anything that deserves wonder and immortality. Great words – and it cannot be otherwise – come from those minds that have significant thoughts. On the lips of persons of the highest spirit, words of rare greatness are found.

The Terror of the Sublime

Edmund Burke (1729–1797) was a British philosopher and politician. He grew up in Dublin, Ireland, which was then part of Britain, and after college education moved to London. He worked in several positions while writing and publishing several philosophy books. In his mid-thirties he entered a political career, was elected to the British House of Commons, and remained there for almost 30 years. As a good speaker he gave many speeches, many of which he later published. He died at the age of 68 after severe stomach problems.

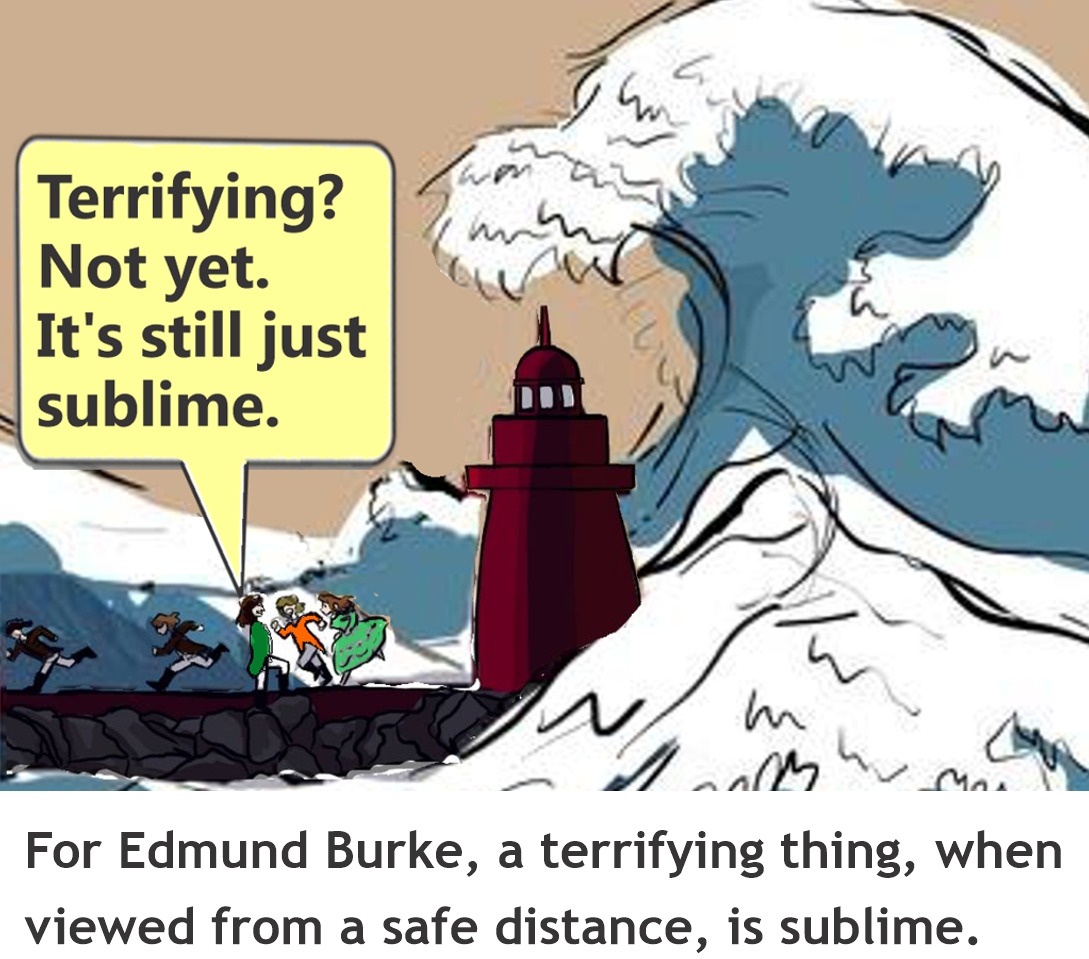

Edmund Burke (1729–1797) was a British philosopher and politician. He grew up in Dublin, Ireland, which was then part of Britain, and after college education moved to London. He worked in several positions while writing and publishing several philosophy books. In his mid-thirties he entered a political career, was elected to the British House of Commons, and remained there for almost 30 years. As a good speaker he gave many speeches, many of which he later published. He died at the age of 68 after severe stomach problems. The following passages are adopted (some linguistic simplification) from one of Burke’s earliest books, Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and BeautifuL (1756). The book is known for being the first to argue that beauty and sublimity exclude each other. While the experience of beauty is pleasant, the experience of the sublime is based on the feeling of terror.

Part 1, Section 7: Of the sublimeWhatever tends in any way to excite the ideas of pain and danger – that is to say, whatever is in any way terrible, or refers to terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror – is a source of the sublime. In other words, it produces the strongest emotion which the mind can feel. I say the “strongest emotion” because I am convinced that the ideas of pain are much more powerful than those of pleasure. […] When danger or pain approach us too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible. But at certain distances, and with certain variations, they may be – and they are – delightful, as we experience every day.

Part 2, Section 1: The emotions caused by the sublime

The emotion caused by what is great and sublime is astonishment. And astonishment is the state of the soul in which all the motions of the soul are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case, the mind is filled so completely with its object that it cannot entertain any other matter, and thus it cannot reason about that object. Hence, the great power of the sublime arises, and this power, far from being produced by reasoning, comes before reasoning, and it moves us with an irresistible force. Astonishment, as I said, is the effect of what is sublime in its highest degree. The weaker effects of the sublime are admiration, reverence, and respect.

Section 2: Terror

No passion robs the mind of all its powers to act and to reason as effectively as fear. Since fear is an apprehension of pain or death, it operates in a way that resembles actual pain. Whatever therefore is terrible to our sight is sublime too, whether because of its great size or some other reason. Because it is impossible to look at anything as insignificant, or contemptible, but also dangerous. There are many animals which, though far from being large, yet are capable of raising ideas of the sublime, because they are viewed as objects of terror, such as snakes and poisonous animals of almost all kinds. And things of great size, if we add to them the idea of terror, become without comparison greater. A vast plain of land is certainly no small idea, and the measure of such a land may be as extensive as the measure of the ocean, but can it ever fill the mind with something so great as the ocean itself? This is because of several causes, but mainly because the ocean is an object of no small terror. Indeed, terror is in all cases, whether openly or latently, the ruling principle of the sublime.

Section 3: ObscurityTo make anything very terrible, obscurity seems in general to be necessary. When we know the full extent of any danger, when we can accustom our eyes to it, much of the fear disappear. Everyone will note this, if he considers how much night adds to our dread, in all cases of danger, and how much the notions of ghosts and goblins, of which nobody can form clear ideas, affect those minds which believe in the popular stories about such beings. Those tyrannical governments which are founded on people’s emotions, and principally on the emotion of fear, keep their leader away from the public eye as much as possible. This policy has been the same in many cases of religion. Almost all the pagan temples were dark. […] For this purpose, too, the Druids performed all their ceremonies in the middle of the darkest woods, and in the shadow of the oldest and most spreading oak-trees.

Section 5: Power

Besides those things which DIRECTLY suggest the idea of danger, and those which produce a similar effect from a mechanical cause, I know of nothing that is sublime which is not some form of power. And this branch of the sublime [=power] rises as naturally as the other two branches [largeness and obscurity] from terror – the common root of everything that is sublime. […] In short, wherever we find strength, and however we look upon power, we shall always observe the sublime as associated with terror, while contempt is associated with a strength that is submissive and harmless.

- Authenticity