|

AGORA - Philosophical Topics Important thinkers on important life-issues |

- Attitudes

- Authenticity

- Death

- Philosophizing

- Friendship

- Beauty

- Happiness

- Inner Freedom

- Inner Truth

- Love

- Meaning

- Music

- Right & Wrong

- Romantic Love

- Sex

- Solitude

- Sublime

- The Other Person

This month's topic: INNER TRUTH

What is inner truth? And how seriously should we take it?

WEEK 1 - Kierkegaard WEEK 2 - Fichte WEEK 3 - Emerson WEEK 4 - Marcel An issue for reflection

WHAT IS INNER TRUTH? AND HOW SERIOUSLY SHOULD WE TAKE IT?

- Sometimes an idea touches me powerfully. It feels so real and true, even though I cannot prove it logically. Do you know that experience?

- Sure. And sometimes it is very brief. All of a sudden, an insight fills my awareness like a powerful flash of understanding.

- Right, and sometimes you can’t put it in words. It’s more like seeing or touching something real, very real.

- And at other times, it may stay with you for a long time, years maybe. It’s a kind of ideal that animates you and inspires you to do something important.

- So we are not talking about one experience, but about a family of several different experiences. What is common to all of them is their intensity, and the sense of something really true or real.

- A sense of “inner truth.”

- A good name. But what is this sense of “inner truth”?

- And also, how seriously should we take it? Is it just a subjective feeling, or does it have objective validity?

SØREN KIERKEGAARD

SUBJECTIVITY IS TRUTH

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) was a Danish philosopher who is regarded as one of the two “fathers” of existentialism (the other one being Friedrich Nietzsche). He was born in Copenhagen to a wealthy family and lived there most of his life in relative loneliness. He was once engaged to marry, but after several months broke his engagement (and the woman quickly married somebody else). His criticism of society and organized religion angered many people and alienated them. He died in a hospital from medical complications at the age of 42. His works became famous only in the 1920s, and they have been very influential ever since.

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) was a Danish philosopher who is regarded as one of the two “fathers” of existentialism (the other one being Friedrich Nietzsche). He was born in Copenhagen to a wealthy family and lived there most of his life in relative loneliness. He was once engaged to marry, but after several months broke his engagement (and the woman quickly married somebody else). His criticism of society and organized religion angered many people and alienated them. He died in a hospital from medical complications at the age of 42. His works became famous only in the 1920s, and they have been very influential ever since.

Kierkegaard’s extensive writings revolve primarily around the issue of how to live truly or authentically (or how to be a Christian, as he sometimes phrases it). For him, truth is subjective, and truly living means living with one’s entire being, with passion and commitment and faith. Most people, however, live a dull life of self-deception, so they do not really live.

The following text is adapted from Kierkegaard’s book Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846), which he wrote under the pseudonym “Johannes Climacus.” In this book, Climacus attacks the idea that religion, specifically Christianity, is an objective belief in certain ideas. Objective thinking is about facts outside the thinker, and the thinker himself is not important. Subjective thought, in contrast, is about the thinker himself and his inwardness, no less than about the object. It is a matter of how the person relates himself and to the issue – his passion, his commitment, his concern, and whether he “appropriates” the issue and makes it his own. Thus, if you believe in the principles of Christianity in an objective way as if it was a scientific theory, without passion and commitment, then you do not really believe truthfully.

For an objective reflection, the truth becomes an object, something objective, and thought points away from the subject. For subjective reflection, the truth becomes a matter of appropriation [making it your own], of inwardness, of subjectivity, and thought must penetrate deeper and deeper into the subject and his subjectivity. Just as in objective reflection, when objectivity appears subjectivity disappears, so here the subjectivity of the subject becomes the final stage, and objectivity disappears. It is not for a moment forgotten that the subject is an existing individual, and that existence is a process of becoming, and that, therefore, the idea that truth is an identity between thought and reality is an illusion of abstraction. This is not because truth is not such an identity, but because the believer is an existing individual, and for him the truth cannot be such an identity as long as he exists as a temporal being.

[…]

All essential knowledge concerns existence; Or, only knowledge that relates to existence is essential – is essential knowledge. All knowledge which is not existential – which does not involve inward reflection, is really accidental knowledge. Its degree and scope are of no importance.

[…]

The highest point of inwardness in an existing person is passion, because passion corresponds to truth as a paradox, and the fact that the truth becomes a paradox is grounded in its relation to an existing individual. The one corresponds to the other. By forgetting that we are existing subjects, we lose passion, and truth stops to be a paradox, but the knowing subject begins to lose his humanity and becomes fantastic. And the truth, likewise, becomes a fantastic object for this kind of knowledge.When the question of truth is raised in an objective manner, the reflection is directed objectively to the truth as an object. The reflection is not about the relationship but about whether he is related to the truth. If that which he is related to is the truth, the subject is in truth. When the question of truth is raised in a subjective manner, reflection is directed subjectively to the individual’s relationship. If the relation’s HOW is in truth, the individual is in truth, even if the WHAT to which he is related is not true.

We may illustrate this by examining the knowledge of God. Objectively, the question is whether the object is the true God. Subjectively, the question is whether the individual is related to a WHAT in such a way that his relationship is a God-relationship. On which side does the truth lie? Ah, let us not go for mediation and say: It is in neither side but in the mediation of both of them.

[…]

If a person who lives in a Christian culture goes to God’s house, the house of the true God, with a true conception of God, with knowledge of God, and prays – but he prays in a false spirit; and if another person who lives in an idolatrous land prays with the total passion of the infinite, although his eyes rest on the image of an idol – where is there most truth? The one person prays in truth to God although he worships an idol. The other person prays in untruth to the true God and therefore really worships an idol.

[…]

The objective accent is on WHAT is said; the subjective accent is on HOW it is said. […] Only in subjectivity is there decision and commitment, so to seek it in objectivity is to be in error. It is the passion of infinity that brings forth decisiveness, not its content. In this way, the subjective HOW and subjectivity are the truth.

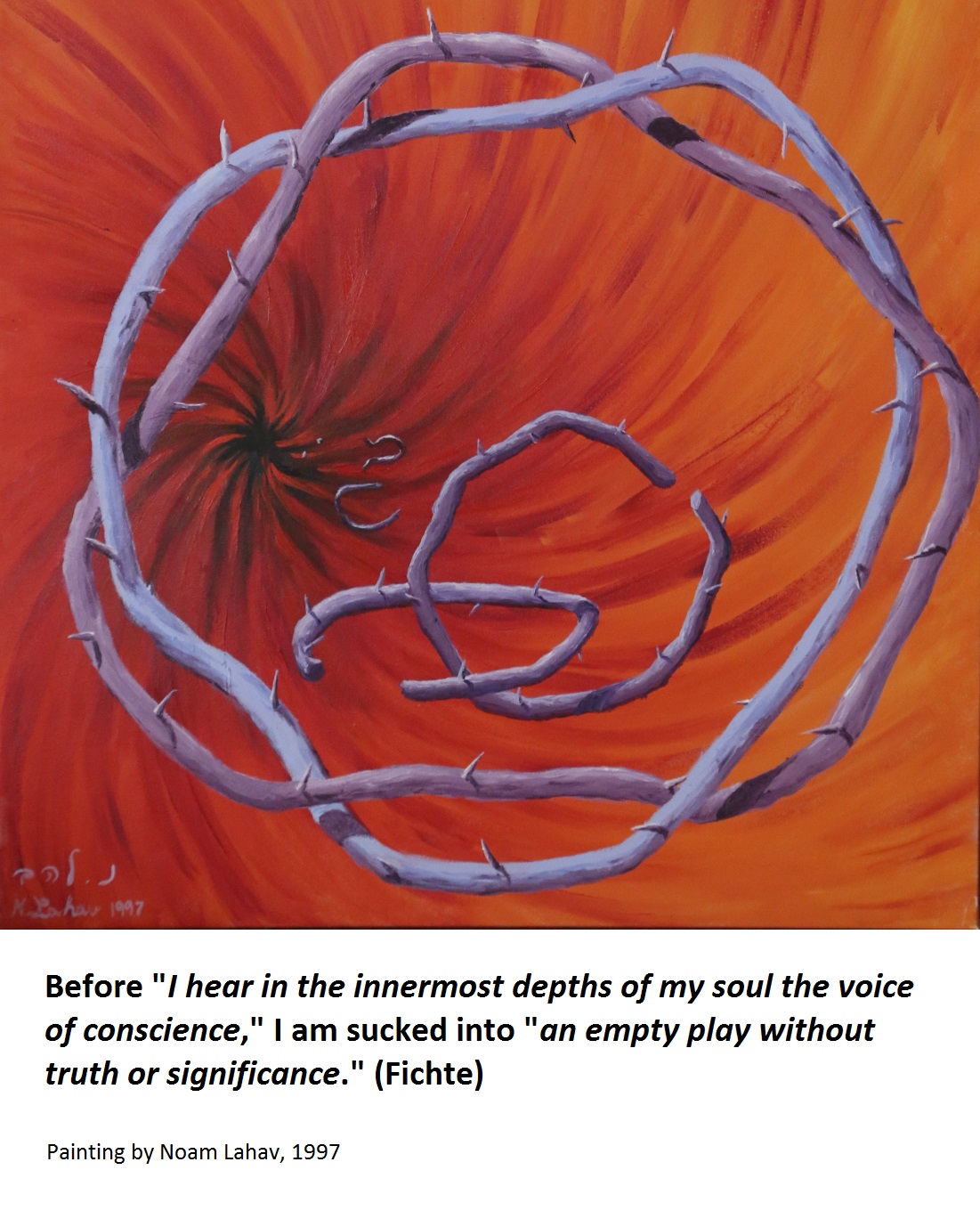

JOHANN GOTTLIEB FICHTE

THE VOICE OF CONSCIENCE

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814) was a major German philosopher, considered to be the founder of German idealism, a philosophical movement of the 18th-19th centuries that revised ideas from Kant’s philosophy. Fichte wrote about a variety of topics, including knowledge, the self, consciousness, religion and morality. For several years he was very influential among German philosophers, but later in his life his popularity declined, eclipsed by Hegel’s influence.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814) was a major German philosopher, considered to be the founder of German idealism, a philosophical movement of the 18th-19th centuries that revised ideas from Kant’s philosophy. Fichte wrote about a variety of topics, including knowledge, the self, consciousness, religion and morality. For several years he was very influential among German philosophers, but later in his life his popularity declined, eclipsed by Hegel’s influence. Fichte was born to a simple family, but he was sent to study in good schools by a local landowner who was impressed by his intellectual abilities. For several years he lived in poverty until, shortly after he married, he was invited to lecture at the important University of Jena. There he suddenly became successful and popular both as a writer and lecturer. During his Jena period, between 1794-1799, he wrote most of his influential books, some of them scholarly and some to the general public. After he was accused of atheism, he moved to the University of Berlin, where he published in 1800 The Vocation of Man, from which the text below is taken, as well as other works. He died from Typhus at the age of 51.

The following text is adopted from Fichte’s book The Vocation of Man, published during his Berlin period in 1800. It deals with the issue of how we can know the world, as well as the issue of our vocation. The first two parts (or “books”) lead to the conclusion that the world might not have independent reality, since it might consist only of representations in my mind. This implies that my life and actions are meaningless. In response to this problem, the third and last book suggests that instead of searching for general systems of understanding I should look into myself. I will then find inside me my will to act, and my moral conscience that tells me how to act. Abstract reasoning cannot prove that this inner call of conscience is real. However, through faith I can accept that my life is not just a meaningless delusion, and that I have a moral duty which I am really called to fulfill – a moral duty that also involves respect for the lives and freedom of others.

In this sense, faith in the voice of my conscience within me – in other words, faith in my moral duty – is more basic than reason-based knowledge. On the basis of this faith, I come to accept that the world is real, that I belong to a higher world, and that my vocation in life is to obey this higher call.

From Book III – “Faith”

“Your vocation is not just to know, but according to your knowledge to act!” — this is what I hear in the innermost depths of my soul, as soon as I recollect myself for a moment, and reflect upon myself. “You are here not for idle contemplation of yourself, not for brooding over your experiences — no, you are here for action. Your worth is determined by your action, and only your action.”

This voice leads me from mere cognition to something which lies beyond it, and is entirely opposed to it: to something which is greater and higher than all knowledge, and which contains the purpose of all knowledge. This voice thus announces to me precisely what I was looking for: something beyond mere knowledge, and completely independent of it.

This is how it is, I know it immediately. But since I have once entered the domain of speculation, the doubt which has been awakened within me secretly continues to disturb me. […] I have to ask myself: Is this really true? From where comes that voice in my soul which directs me to something beyond mere appearances and knowledge?

[...]

Shall I then refuse to accept that inward voice? I will not do so. I will freely accept the vocation which this impulse gives me. And in this decision I will immediately hold this thought, in all its reality and truthfulness, and the reality of all the things which this thought presupposes. […]

I have found the organ with which to understand this reality, and probably all other reality. This organ is not knowledge — no knowledge can be its own foundation, its own proof. Every knowledge presupposes another higher knowledge on which it is based, and so on with no end. It is faith that voluntarily accepts the view which naturally appears to us, because only through this view we can fulfill our vocation. This produces knowledge, and raises to certainty and conviction its basis: not knowledge, but a resolution of the will to admit the validity of knowledge.

[...]

This voice of my conscience announces to me precisely what I must do and what I should not do in every particular situation of life. It accompanies me, if I only listen to it with attention, through all the events of my life, and it never frustrates me where I am called to act. It carries with it immediate conviction, and irresistibly forces me to agree to its commands – it is impossible for me to oppose it. To listen to it, to obey it honestly and with no reservation, without fear or evasion — this is my true vocation, the whole purpose of my existence. My life stops being an empty play without truth or significance. There is something that must absolutely be done for its own sake alone. What conscience demands of me in this particular situation of life is mine to do, and this is why I am here. To know it, I have understanding; to perform it, I have power. Only through this conscience, truth and reality enter into my conceptions. I cannot refuse them my attention and my obedience without surrendering the purpose of my own existence.

[...]

But the voice of my conscience says: “Whatever these [other human] beings may be by themselves, you should act towards them as self-existent, free, substantive beings, wholly independent of you. Assume that they can give a purpose to their own being wholly by themselves, and quite independently of you. Never interrupt this purpose, but rather further it as much as you can. Honor their freedom, lovingly take care of their purposes as if they were your own.” This is how I should act. All my thoughts must be guided by this course of action — it will be so, and must necessarily be so, if I have decided to obey the voice of my conscience.

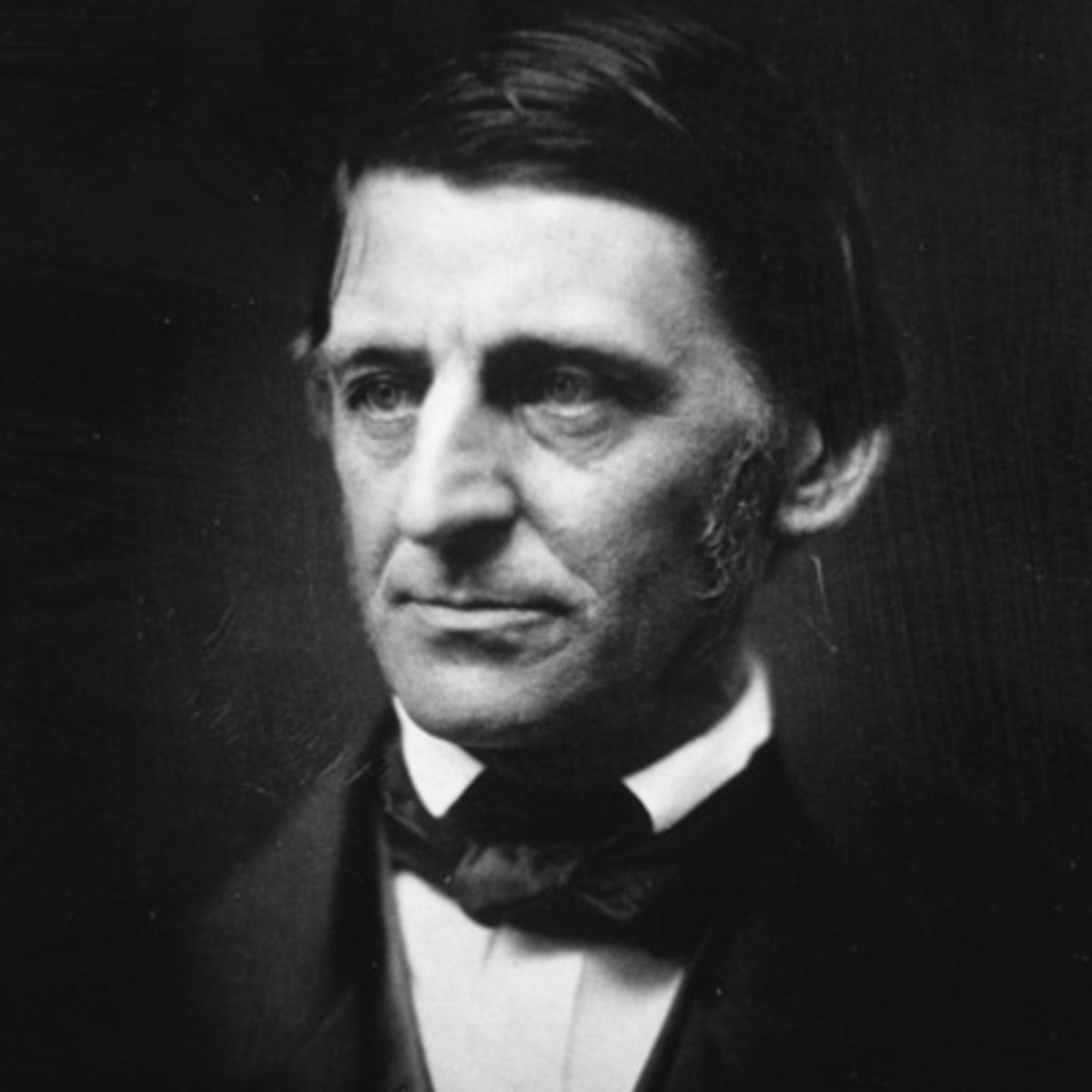

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

THE OVER-SOUL

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was an American philosopher, poet, and inspiring speaker. He was born in Boston and went to Harvard College. In 1837 he founded, together with other American intellectuals, the “Transcendental Club,” which promoted openness to the deep, poetic aspects of reality. Throughout his life he wrote many inspiring papers and gave many moving lectures around the country, and was regarded as the leader of the transcendentalist movement (an American movement of the 19th century). He was also known for his opposition to slavery. He died at the age of 78 from pneumonia.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was an American philosopher, poet, and inspiring speaker. He was born in Boston and went to Harvard College. In 1837 he founded, together with other American intellectuals, the “Transcendental Club,” which promoted openness to the deep, poetic aspects of reality. Throughout his life he wrote many inspiring papers and gave many moving lectures around the country, and was regarded as the leader of the transcendentalist movement (an American movement of the 19th century). He was also known for his opposition to slavery. He died at the age of 78 from pneumonia.

The following are selected passages from Emerson’s famous essay “The Over-Soul” (some sentences slightly simplified). For Emerson, the “over-soul” (which he sometimes calls simply “the soul”) is a higher dimension of existence which is the source of inspiration, insight, and wisdom. It is an aspect of reality which inspires us to understand more deeply, to envision sublime visions, to think and write poetically, and to open ourselves beyond our little self. The over-soul is not a separate “thing” or “entity.” It is, rather, an aspect of existence which envelop us and which can elevate us, like a hidden fountain of higher life.

Man is a stream whose source is hidden. Our being descends into us from we know not where. The most exact calculator cannot predict that something incalculable may not happen the very next moment. I am forced every moment to acknowledge a higher origin of events than the will which I call “mine.”

As with events, so is it with thoughts. When I watch that flowing river which, out of regions I don’t see, pours for a while its streams into me, I see that I am a pensioner – not a cause, but a surprised spectator of this ethereal water; that I may desire and search and be receptive, but from some alien energy the visions come.

The Supreme Critic on the errors of the past and the present, and the only prophet of that which must be, is that great nature in which we rest, just as the earth lies in the soft arms of the atmosphere. It is that Unity, that Over-soul, which contains every individual’s particular being and where it is made one with all other beings; that common heart which every sincere conversation worships, to which all right action submits; that overpowering reality which invalidates our tricks and talents, and forces everyone to be what he is, and to speak from his character and not from his tongue, and which always tends to pass into our thought and hand and become wisdom, and virtue, and power, and beauty.

We live in succession, in division, in parts, in particles. Meantime, within each person is the soul of the whole, the wise silence, the universal beauty, to which every part and particle is equally related, the eternal ONE. And this deep power in which we exist, and whose beatitude is all accessible to us, is not only self-sufficient and perfect in every hour; furthermore, the act of seeing and the thing that is seen, the seer and the spectacle, the subject and the object, are one. […]

All goes to show that the soul in a person is not an organ, but animates and exercises all the organs. It is not a function – like the power of memory, of calculation, of comparison, but it uses these as hands and feet. It is not a faculty, but a light. It is not the intellect or the will, but the master of the intellect and the will, the background of our being in which they lie — an immensity that is not possessed and that cannot be possessed. From within or from behind, a light shines through us upon things, and makes us aware that we are nothing, but the light is all. Man is the façade of a temple where all wisdom and all good dwell.

[…]

We refer the announcements of the soul, the manifestations of its nature, with the term Revelation. These are always joined by the emotion of the sublime. Because this communication is an influx of the divine mind into our mind. It is an ebb of the individual rivulet before the flowing surges of the sea of life. Every distinct experience of this central commandment agitates the person with awe and delight. A thrill passes through everyone at the reception of new truth, or at the performance of a great action, which comes out of the heart of nature. In these communications, the power to see is not separate from the will to do, but the insight proceeds from obedience, and the obedience proceeds from a joyful perception. Every moment in which the individual feels himself invaded by it – is memorable.January Week 4 quotation

GABRIEL MARCEL

PROFOUND IDEAS ARE CLOSE TO MY ROOTS

Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973) was a French existentialist philosopher, playwright, pianist and music critic, who wrote about the human condition in the modern world. He studied philosophy under Henri Bergson and others at the University of Paris and the Sorbonne. He grew up an atheist, but converted to Catholicism at the age of 40, and his writings have a vaguely spiritual orientation. Although he is regarded as an existentialist, his philosophy is very different from that of Sartre, whom he often criticized. Marcel’s world has the possibility of true togetherness, hope, and meaning. His philosophical writings are not easy to read – they are usually like musical themes developing in complex ways, rather than a linear theory.

Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973) was a French existentialist philosopher, playwright, pianist and music critic, who wrote about the human condition in the modern world. He studied philosophy under Henri Bergson and others at the University of Paris and the Sorbonne. He grew up an atheist, but converted to Catholicism at the age of 40, and his writings have a vaguely spiritual orientation. Although he is regarded as an existentialist, his philosophy is very different from that of Sartre, whom he often criticized. Marcel’s world has the possibility of true togetherness, hope, and meaning. His philosophical writings are not easy to read – they are usually like musical themes developing in complex ways, rather than a linear theory.

The following text is adapted from Marcel’s major book The Mystery of Being (1951). Here Marcel explains what it means to say that an idea is deep or profound. A profound idea is not easily accessible to me, it is not here with me – it is hidden, it is far from the visible surface of my mind. Therefore, a profound idea is distant from me. But it is also nearby. It is close to my essence, it is close to my roots. A profound idea is like my home-land, the land where I was born: This land may be far away, but it is also here in my blood. To put it differently, a profound idea is like a promise – it points to a future clarification and understanding, but it also relates to the distant past, back to my roots. Therefore, a profound idea is far and near at the same time, and in this sense it is beyond space and time.

From CHAPTER 9

I would say that we feel a thought as deep, or an idea as profound, if it emerges into a region beyond itself, a vast region that is more than the eye can grasp. […] Our experience of depth is connected to the feeling that a promise is being made, but that we can grasp only a glimpse of the fulfillment of that promise.

However, we should notice that this glimpse of a distant prospect – this shining “over there” as we might call it – is not something we feel as being “elsewhere.” We would have to describe it as distant, yet we also feel it as intimately near us. We have to transcend the spatial and pragmatic distinction between what is here and what is somewhere else.

The distance appears to us as an inner distance, as what we can describe as a land for which we are home-sick. This is, in fact, exactly how the exiled person experiences his lost homeland. A person’s homeland may be distant, but it has a connection with him that cannot be broken. This longing is different from the dream which he had in his youth for an exotic foreign country, because that foreign country (however vividly he imagined it) remains in the imagination, a “somewhere else.” In contrast, a person’s own country is not something imaginary, it is in the blood.

We must therefore focus on the condition of a person who isn’t fully identified with his actual surroundings. Some coincidence has exiled him to where he is now, and his place is his place only by chance. In the current conditions to which he must submit, this real place can only be seen as a “beyond,” as the home of home-sickness.

[…]

Let us notice, however, that what we expressed in terms of space could also be expressed in terms of time. And this change of key is of great interest to us here. In terms of time, a deep thought or a profound idea pushes further ahead, in other words it opens a path that can be followed only in time. It is like an intuitive dive into an investigation which can be developed only over a long period of time – a personal, lived, human time.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to interpret the idea of depth simply in terms of the future. From our present perspective, the future cannot be regarded as simply something new, as something unexpected which simply replaces the old present. The novelty of the future may be very attractive, but when we move into the future we don’t feel that we are moving into depth just because we are moving towards something new.

The concept of depth appears only when we think about the future as somehow mysteriously in harmony with the most distant past. We might even say that in the dimension of depth, the past and the future hold hands in a firm way. They do so in a region which, from the perspective of all our here’s-and-now’s, can be described as the absolute Here-and-Now. And this region, where the NOW and THEN tend to merge, like the NEAR and the FAR in our previous illustration, would be nothing other than Eternity.

[…]

This is the mysterious linking of the future and the past, which can in reality take place only on some level which transcends the world of cause and effect. […] For now it is sufficient that my discussion of these very difficult ideas gives us a glimpse of the sense in which the opposition between the successive and the abstract can be transcended at a supra-temporal level which is also the very depth, or inwardness of time.

- Authenticity