|

AGORA - Philosophical Topics Important thinkers on important life-issues |

- Attitudes

- Authenticity

- Death

- Philosophizing

- Friendship

- Beauty

- Happiness

- Inner Freedom

- Inner Truth

- Love

- Meaning

- Music

- Right & Wrong

- Romantic Love

- Sex

- Solitude

- Sublime

- The Other Person

This month's topic: THE OTHER PERSON

What does it mean to encounter another person?

WEEK 2 - Buber WEEK 3 - Levinas WEEK 4 - Marcel WEEK 5 - Picard An issue for reflection

What does it mean to encounter somebody?

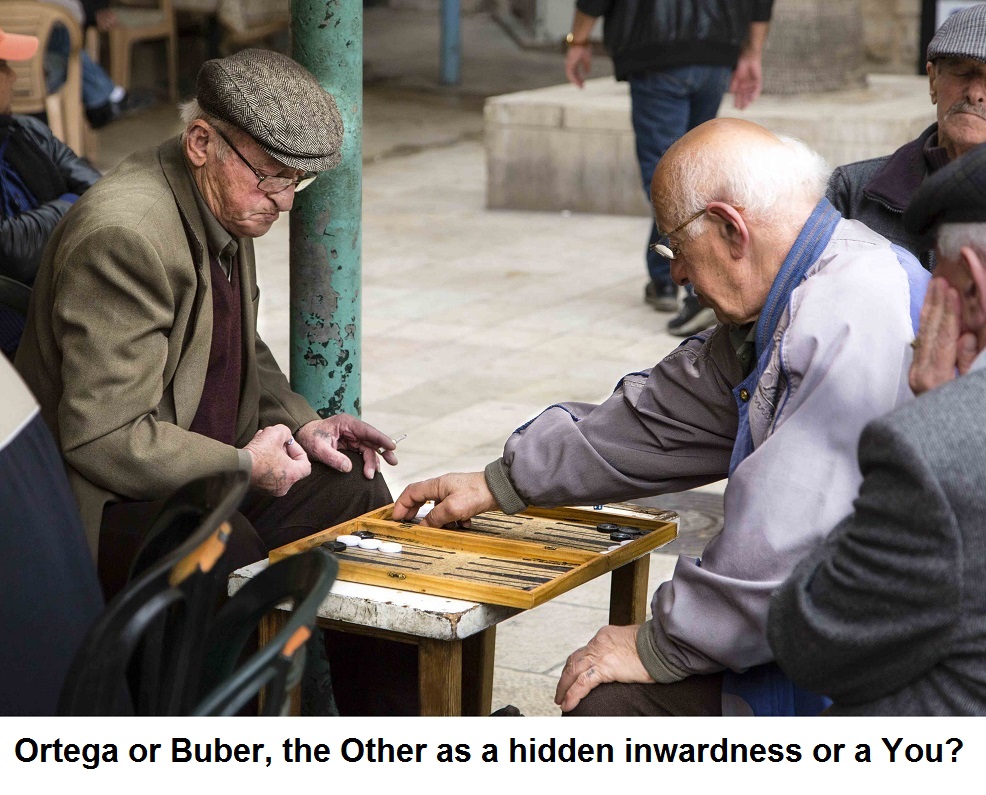

The winning caption of this month's competition is:

Look at me, look at me, look at me - I want to exist!

This time, the winner is an Agora team member, Ran Lahav (who, of course, did not participate in the selection of the winner). The winner is always selected anonymously by all the Agora team members who are not participating in the competition, and who do not know who is participating.

The competition: The above photo needs a caption (a text). Send us your suggestion! A caption can be a title, or the words of a person in the picture, etc.

Maximum length: 20 words.

Send to: Ran, Carmen, or info@PhiloPractice.org

Deadline: The third Saturday of the month.

The Agora team will select the most philosophical, and/or smartest, and/or funniest caption. The winning caption will be placed under the photo, together with the winner's name.

I am alone in the room. There is a table, and two chairs, and a painting on the wall – but these objects don’t interrupt my alone-ness. Even with these objects, I am still alone. I am me and nothing else.Suddenly, somebody enters the room, and I am not alone anymore. I feel different now.

What happened? What did this “somebody” do to me, which the table and the chairs and the painting couldn’t do? Did he change me?

I am with somebody now, and his presence brings me new possibilities: I can joke together, I can fight, I can be jealous or compassionate or embarrassed or loving. What does this “somebody” mean?

JOSE ORTEGA Y GASSET

The other as a dangerous inwardness

José Ortega y Gasset (1883-1955) was an influential Spanish philosopher. His philosophy, which unites existentialist, phenomenological, and pragmatist themes, attempts to relate to life as it is lived, instead of remote abstract ideas. He taught at the University of Madrid and elsewhere, and was briefly a parliament member. He left Spain at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, and went to exile in Argentina and then Portugal. He returned to Spain in 1948, where he founded the Institute of Humanities. The following passages are adapted from Ortega’s book Man and People, published in 1957 on the basis of lectures which he gave at the Institute of Humanities (1949-1950). In this book he analyzes human society, starting from the self, then the other person, the We and the You, people, language, and public power.

The following passages are adapted from Ortega’s book Man and People, published in 1957 on the basis of lectures which he gave at the Institute of Humanities (1949-1950). In this book he analyzes human society, starting from the self, then the other person, the We and the You, people, language, and public power.

An important theme in Ortega’s writings is a basic duality in the person: On the one hand, a person is an inwardness – a private, inner world of feelings and thoughts which nobody else can access. But on the other hand, a person can also transcend the boundaries of his inner world, and relate to other people. We can see this duality, for example, in Ortega’s essays on love: Love is a psychic flow from my inner world towards another person (and this, Ortega says, also applies to hate).

A similar duality appears in the text below, on the other person: The other person is an inwardness that is hidden from me. But through his body, and especially through his face and eyes, his inwardness reveals itself to me, in part. This is why I can communicate with the other person, and why we can co-exist together.

How do the “other persons” appear in my life-world? The moment this question is asked, we feel a change of mood. So far, we have been relaxed and calm. Now, when we hear that our horizon of reflection is going to be invaded by “other persons,” we feel a slight uneasiness – we don’t know why – as if a subtle electric current ran through our backs. You can think about it as absurd as you like, but it is a fact.

[…]

“Who goes there?!” We are no longer careless and relaxed, but on guard and cautious. It seems that the other persons are so terrifying! This is the suspicious origin of our uneasiness: We are going to talk about beings (people) whom we know can have an opinion about us. This has put us on guard, with our souls alert. On the gentle horizon of the paradise-world, a danger appears: the other person.

[…]

I perceive the other person only as a body, a body that has a specific form, that moves, that manipulates things – in other words, that shows external, visible behavior. But the surprising and strange thing is that although what is present to us is only a figure and some bodily movements, in (or through) this presence we see something that is essentially invisible. This is something that is pure inwardness, something that each one of us knows directly only in himself: his thinking, feeling, desiring. These operations cannot be present to other persons. They are pure inwardness.

[…]

I said before that our encounter with an animal has an element of co-existence. This co-existence arose because the animal responds to us from an inner center which is inside it, in other words from its inwardness. All co-existence is a co-existence of two inwardnesses. And the extent of co-existence is precisely the extent to which these two inwardnesses somehow become present to each other.

[…]

For example, I see that a body is looking. The eyes, “windows of the soul,” show us more about the other man than anything else – because looks are like acts that come from the inside. We see what it is looking at, and how it is looking. Not only does the look come from the inside, we also observe from what depth it comes.

[...]

I said that the Other, the pure Other, the unknown person, forces me to anticipate his possible hostile and violent reactions, since he is unknown and I don’t know how he will behave toward me. This is equivalent to saying that the other is essentially dangerous

[…]

The danger is not necessarily evil and adverse. It can be the contrary, beneficial and helpful. But as long as it is dangerous, the two opposite reactions are equally possible.

[…]

The Other Person is, then, essentially dangerous. And this characteristic, which is strongest in the case of a completely unknown person, becomes less and less as he becomes “you” for us, but it never disappears entirely. Every other human being is a danger to us — each one in his own way and in his particular degree.

MARTIN BUBER

I-It and I-You

Martin Buber (1878-1965) was a Jewish Israeli philosopher, writer, and an activist of cultural Zionism. He was born in Austria, became a professor in Frankfurt, but after the rise of Nazism left for Israel (then Palestine, under British mandate). He wrote on Hassidism and mysticism, but is best known for his dialogical philosophy, which understands human beings in terms of their relations with each other. The following passages are adopted from Part I of Buber’s philosophical-poetic book I and Thou. (“Thou” in English means “you” in the singular). Buber’s starting point is the idea that human beings are not atoms standing by themselves. A human being is a person-in-relation. Relationships come first – to others, to animals and plants, to ideas and works of art, to God.

The following passages are adopted from Part I of Buber’s philosophical-poetic book I and Thou. (“Thou” in English means “you” in the singular). Buber’s starting point is the idea that human beings are not atoms standing by themselves. A human being is a person-in-relation. Relationships come first – to others, to animals and plants, to ideas and works of art, to God.

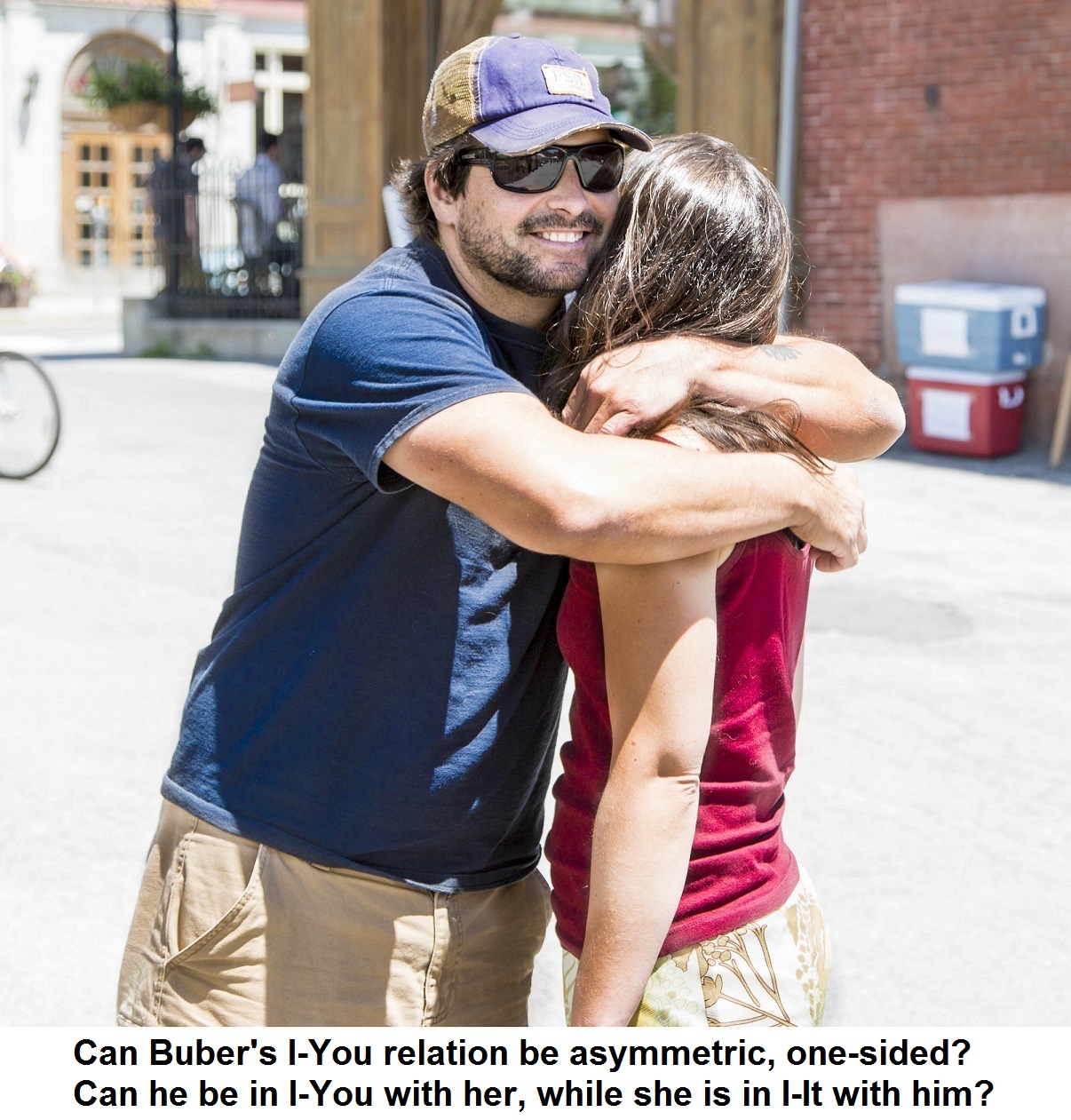

Buber distinguishes between two fundamental kinds of relationships: I-It relations and I-Thou (I-You) relations. In I-It relations, I regard somebody as an object, as an ”it.” The other is an object for me (object of thought, object of interest, object of experience, of manipulation, of pity, etc.). In contrast, in I-Thou relations, I relate to somebody as a You. I am in togetherness with him – fully, with my whole being, without objectifications or boundaries. And since I am defined by my relationships, I am different when I am in I-You and when I am in I-It.

The world is two-fold for man, according to his two-fold attitude. A man’s attitude is two-fold according to two words which he can speak. The basic words are not single words, but words in pairs..One basic word is I-You. The other basic word is I-It. But this basic word doesn’t change when “He” or “She” comes instead of “It.” Therefore, man’s I is also two-fold. Because the “I” of I-You is different from the “I” of I-It.

* * *Basic words do not refer to something that exists outside them. By being spoken, they establish a mode of existence.

Basic words are spoken with one’s being. When one says “You,” the “I” of the double-word I-You is said too. When one says “It,” the “I” of the double-word I-It is said too.

The basic word I-You can only be spoken with one’s whole being. The basic word of I-It can never be spoken with one’s whole being.

* * *

There is no I by itself, but only the I of I-You and the I of the I-It. When a person says “I,” he means one or the other. The “I” he means is present when he says “I.” And when he says “You” or “It,” the ”I” of one or the other basic word is also present. Being “I” and saying “I” is the same. Saying “I” and saying one of the two basic double-words are the same. Whoever speaks one of the basic words enters into the word and stands in it.

* * *

I perceive something. I feel something. I imagine something. I want something. I sense something. I think something. The life of the human being does not consist only of all this, and its like.All this is the basis of the domain of It. But the domain of You has another basis.

* * *

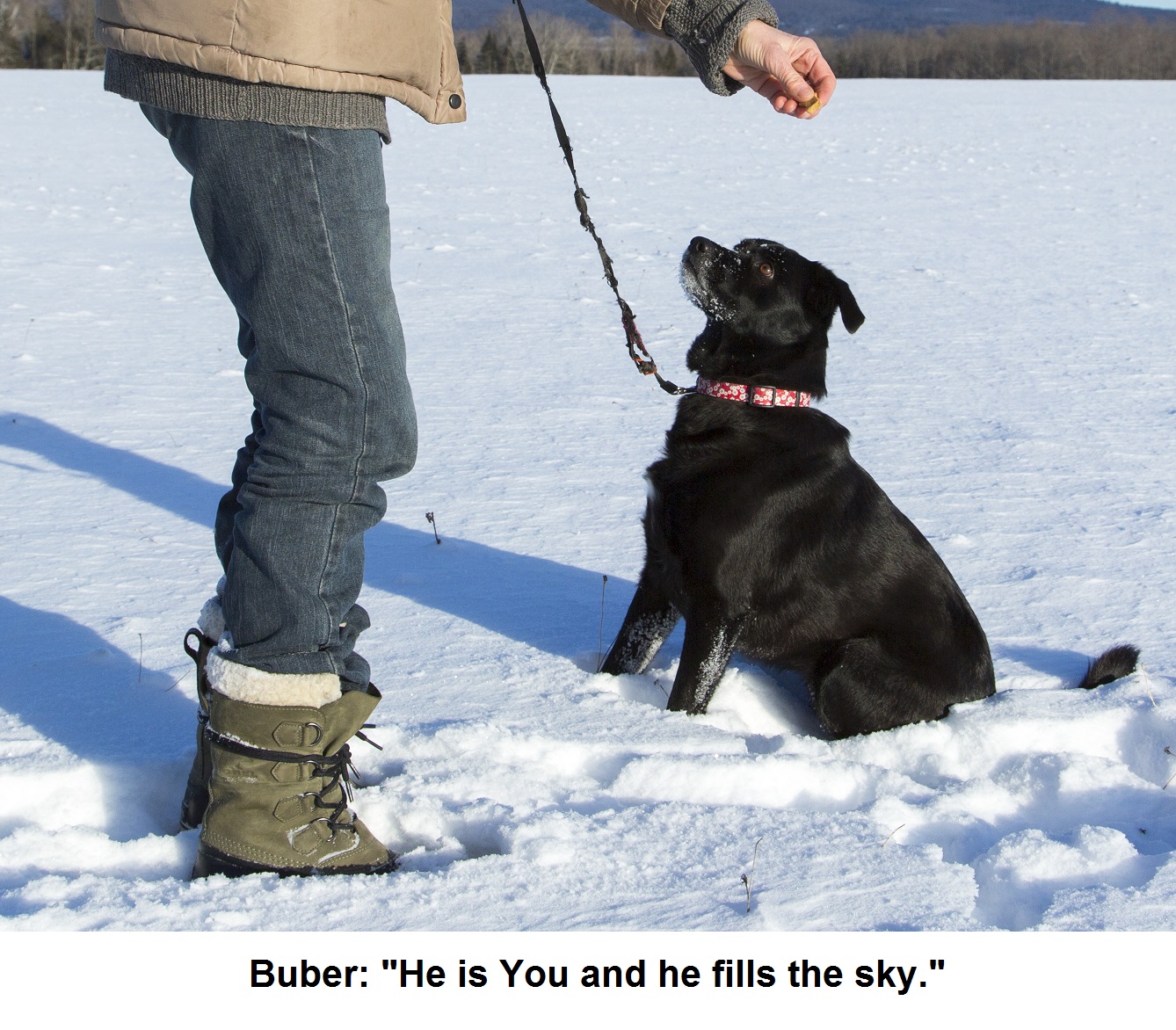

Whoever says You does not have something as his object. Because where there is “something” there is also another something. Every It borders on other Its. It is only because it borders on other Its. But where there is You, there is no something. You has no borders.

Whoever says You does not have something. He has nothing. But he stands in relation.

* * *

When I encounter a human being as my You and I say to him the basic word I-You, then he is not a thing among things, and he doesn’t consist of things.He is no longer He or She, limited by other Hes and Shes, a dot in the world-grid of space and time. Nor is he a condition that can be experienced and described, a collection of certain qualities. Without neighbors and without division, he is You and he fills the sky. It’s not as if there is nothing except for him, but rather everything lives in his light.

Just as a melody is not made of tones, and a poem is not made of words, and a statue is not made of lines (I must pull and tear it in order to turn unity into multiplicity), the same is with a You. I can abstract from him the color of his hair, or the color of his speech, or the color of his kindness. I have to do this again and again, but immediately he is no longer You. [...]

I do not experience the person I call You. But I stand in relation to him, in the sacred basic word of You. Only when I step out of this, I experience him again. Experience is a distance from You.

* * *

The relation to the You is not mediated by anything. Nothing conceptual stands between I and You, no prior knowledge, no imagination. And memory itself is changed as it goes from particularity to wholeness. No purpose intervenes between I and You, no greed and no anticipation. […] Only when all the means have disintegrated, a meeting occurs.

* * *

Without It a human cannot live. But whoever lives only with It is not human.

EMMANUEL LEVINAS

The face of the Other

Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995) was a Jewish French philosopher. He grew up in Lithuania and received Jewish education, and moved to France to study philosophy in 1924. Drafted to the French military, he spent much of World War II as a prisoner of war in Germany, and as a Jewish prisoner he experienced considerable hardship. After the war he continued to teach and write about Jewish thought and about philosophy. In the 1950s he started to be considered a major thinker in French philosophy. The following passages are adapted from Levinas’ essay “Ethics as a First Philosophy.” (Some sentences are simplified, because of Levinas’ complex style.) This text expresses a central theme in Levinas’ philosophy: that ethics comes first, before any objective metaphysics or theory of knowledge.

The following passages are adapted from Levinas’ essay “Ethics as a First Philosophy.” (Some sentences are simplified, because of Levinas’ complex style.) This text expresses a central theme in Levinas’ philosophy: that ethics comes first, before any objective metaphysics or theory of knowledge.

For Levinas, the other person is not an object, and he cannot be known. He is an otherness, an alterity. The encounter with the Other comes even before any philosophical knowledge, even before self-consciousness or consciousness-of. It is the starting point of philosophy.

The Other appears to me through his face, and the face is exposed, naked, vulnerable. This vulnerable face is a call to me: “Don’t kill me!” In this sense, the potential death of the Other appears in his face. Therefore, the face is an ethical demand that is directed at me. I am responsible for the other, unconditionally responsible. And this infinite responsibility has a trace of infinity, in other words God and his ethical command.

In my philosophical essays, I have spoken a lot about the face of the Other as being the beginning of everything that can be experienced. May I now briefly describe again how the face erupts into the phenomenal world of appearances?

The proximity of the other is the meaning of the face. And this meaning goes beyond the shapes that try to cover the face like a mask which is present to perception. But the face always appears through these shapes. Before any particular expression, and under all particular expressions which cover and protect the Other with a face or expression, there is nakedness and destitution. In other words – extreme exposure, defenselessness, vulnerability. […] From the beginning there is in the face exposure to invisible death, to a mysterious abandonment. Beyond the visibility of whatever is seen, and before any knowledge about death, there is mortality in the Other.

[…]

But, in its mortality, the face before me summons me, calls for me, begs me, as if the death which must be faced by the Other is my business. It is as if this invisible death, which is not noticed by the Other, is already “regarding” me before confronting me, and becoming the death that looks at me in the face. The other man’s death calls me into question, as if, through the indifference which I might show in the future, I am a collaborator with the death to which the Other is exposed. And as if I had to justify myself for the death of the Other, and to accompany the Other in his mortal solitude. The Other becomes my neighbor precisely through the way the face summons me, calls for me, and thus reminds me of my responsibility, and calls me into question.

Responsibility for the Other, for the naked face of the first individual who comes along. A responsibility that goes beyond what I did or didn’t do to the Other, as if I was devoted to the other man before I was devoted to myself. Or more exactly, as if I had to justify myself for the Other’s death even before being. A guilt-less responsibility, in which I am nevertheless open to an accusation which no alibi could clear me. […] A responsibility that comes from a time before my freedom – before my beginning, before any present. […] Responsibility for my neighbor comes from a past that was never present, and is more ancient than any consciousness-of. A responsibility for my neighbor, for the other man, for the stranger or resident [in the words of the Bible], which is not because of anything in the ontology of the world – not because of anything in the order of things, of the “something”, of “number”, or “causality”.

GABRIEL MARCEL

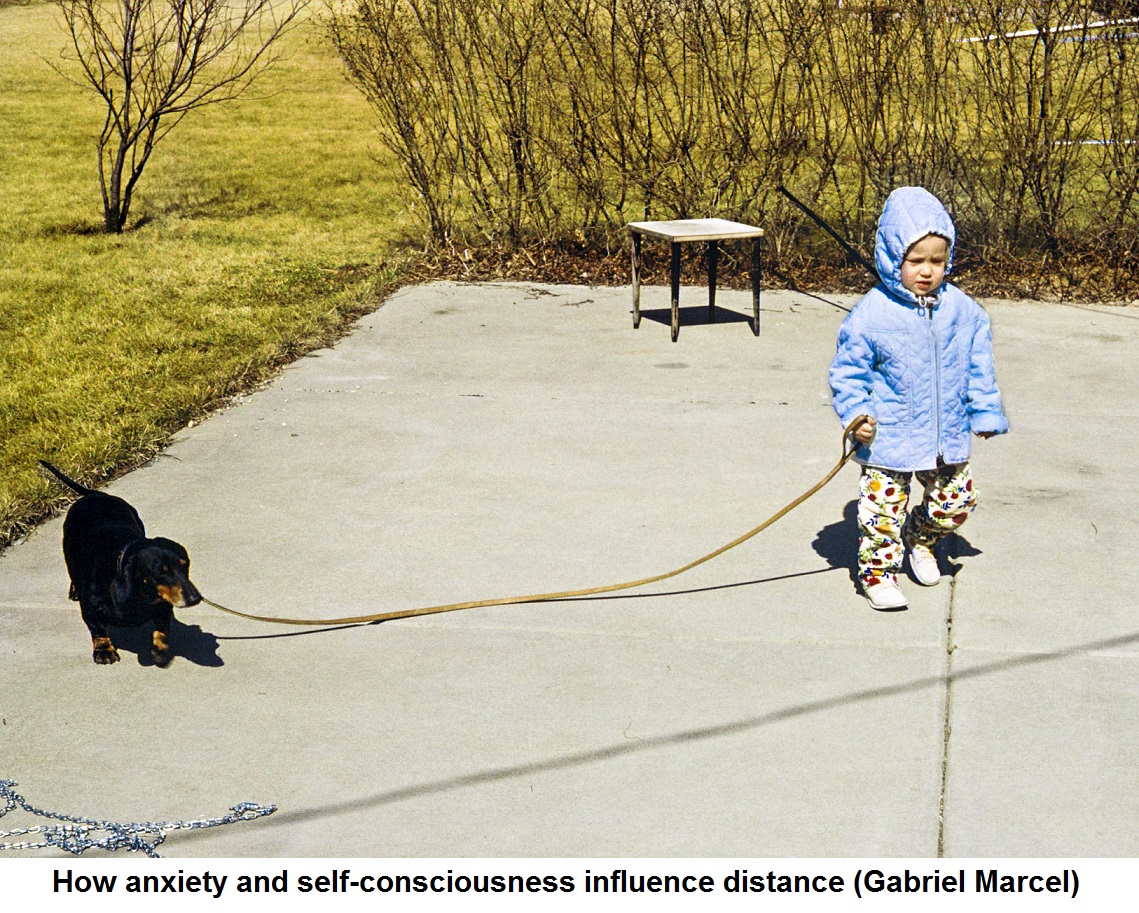

Together is "elsewhere," away from my self

Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973) was a French philosopher, playwright, and music critic. He grew up as an atheist, but converted to Catholicism at the age of 40. As a philosopher he did not want to include specific religious ideas in his writings, but his philosophy nevertheless has a general spiritual orientation. Although he is regarded as an existentialist, his philosophy is very different from that of Sartre, whom he often criticizes. Unlike Sartre’s empty and lonely world, Marcel’s world has the possibility of true togetherness (“inter-subjectivity”), hope, and faithfulness to a light.

Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973) was a French philosopher, playwright, and music critic. He grew up as an atheist, but converted to Catholicism at the age of 40. As a philosopher he did not want to include specific religious ideas in his writings, but his philosophy nevertheless has a general spiritual orientation. Although he is regarded as an existentialist, his philosophy is very different from that of Sartre, whom he often criticizes. Unlike Sartre’s empty and lonely world, Marcel’s world has the possibility of true togetherness (“inter-subjectivity”), hope, and faithfulness to a light.The following text is adapted from Marcel’s major book The Mystery of Being (Part I, Chapter 9). Here he explains that the way you relate to another person depends on how you relate to yourself. You can be self-conscious of yourself, absorbed in yourself, behaving as special, different, vulnerable. You are then making yourself a separate ego, here-and-now. But alternatively, you can let go of your anxious self-consciousness, and allow yourself be WITH the other person. You are no longer absorbed in yourself, no longer here-and-now, but in a different domain of existence, in a kind of “elsewhere.”

The child, let us say, runs up to his mother and offers her a flower. “Look,” he says, “that was me. I picked it!” His tone and gestures are very significant. He is pointing to himself as somebody who deserves admiration and gratitude from the adults. “Look, it is I, I in person, I, all present right here, who have plucked this flower! Above all, don’t believe for a moment that it was Jim or Lucy who picked it!”

The child’s “I did it!” prevents the terrible misunderstanding of attributing my achievement to others. But we also find adults defending the ego’s rights in the same way. Let us take the example of the amateur composer who sings a song for which he has written the melody. Some innocent listener asks: “Was it Debussy? “Oh no,” replies the composer, smiling proudly, “that was a little piece which I wrote.”

Here again the ego is trying to attract to itself the praise, the surprised and admiring comments, of somebody other than itself, and he uses him as a reflecting board. In cases of this sort, the ego is present in the flesh, requesting or protesting in various tones of voices, that nobody should violate its rights, or step on its toes.

[…]

[Imagine] a shy young man who appears for the first time at a fashionable dance or cocktail party. Such a young man is self-conscious to the highest degree […] It seems to him that everybody at the party is looking at him – with what meaningful looks! Obviously they are making fun of him, perhaps because of his new dinner jacket which does not fit him as it should, perhaps because of his new bow-tie […] Thus, he is preoccupied with himself to the highest possible degree, and at the same time he is hypnotized by others – by what he imagines other people think of him. This paradoxical tension is nicely expressed by the excellent English word “self-consciousness.”

This tension is the opposite of what I have called “inter-subjectivity.” And this opposition cannot be over-emphasized. Imagine that an unknown person comes to our party to say a word or two to the shy man. At first, the young man doesn’t enter into the direct relation that is expressed by the pronoun “you.” Instead, he thinks of him as “him.” Why is he talking to me? What does he want? […] Since he is defensive, our young man has almost no conversation "with" him. He is not really "with" the other more than he must be.

Very generally, we can say that the relationship expressed by the preposition “with” is very inter-subjective. The relationship of “with” does not apply to the world of objects, which is a world of side-by-side. A chair is alongside a table, or beside it. Or, we put the chair by the table. But the chair is never really with the table in this sense.

But now, let’s imagine that the ice is broken, and that the conversation becomes more intimate. “I am glad to meet you,” says the stranger. “I once knew your parents.”

And suddenly a link is created, and importantly – the tension relaxes. The attention of the young man is no longer concentrated on himself. He is lifted out of the here-and-now, and strangely, this unknown person accompanies him on this sort of magic voyage. They are together in what we must call an “elsewhere” – but an elsewhere which has a mysterious intimate character. Let us say that a shared secret links them together.

[…]

To make this point clearer, we can say that relationships between things are external, and between people they are internal. When I put the table beside the chair, I don’t make any difference to the table or the chair, and I can take it away without making any difference. But my relationship with you makes a difference to both of us, just as any interruption of the relationship makes a difference.

MAX PICARD

Silence listening to people speak

Max Picard (1888-1965) was a Swiss philosopher who wrote in German. As a young man he started a career in medicine, but after a short time in several university clinics, decided to quit and devote his life to writing. As a writer and non-academic philosopher he became well-known in Germany, as well as in other countries, and was a friend of intellectuals such as Rilke, Gabriel Marcel, and Gaston Bachelard. He was a lover of solitude and nature, and many came to visit him for his wisdom and advice.

Max Picard (1888-1965) was a Swiss philosopher who wrote in German. As a young man he started a career in medicine, but after a short time in several university clinics, decided to quit and devote his life to writing. As a writer and non-academic philosopher he became well-known in Germany, as well as in other countries, and was a friend of intellectuals such as Rilke, Gabriel Marcel, and Gaston Bachelard. He was a lover of solitude and nature, and many came to visit him for his wisdom and advice.The following passages are from Picard’s poetic-philosophical book The World of Silence. Picard suggests that our conversations with others are rooted in silence. Silence is found in every encounter between people. This is because silence is a fundamental aspect of reality, which is present and active in most aspects of our life. Silence is not just an absence of sounds and noises – it has an independent existence in our lives which is original and creative. It is not something we can see, and yet we can sense its presence very concretely just “as we can feel our own bodies.”

Silence is original and self-evident like the other basic phenomena – like love, and like loyalty, and death, and like life itself. But it existed before all these, and it is in all of them. Silence is the first-born among all basic phenomena. It envelops the other basic phenomena – love, loyalty, and death. And there is in them more silence than speech, more of the invisible than the visible.

Speech came out of silence, out of the fullness of silence. The fullness of silence would have exploded if it had not been able to flow out into speech.

[…]

Whenever a person begins to speak, the word comes from silence at each new beginning. It comes so obviously and so unobtrusively as if it was only the reverse of silence, only silence reversed. Speech is in fact the reverse of silence, just as silence is the reverse of speech.

There is something silent in every word, as a long-lasting mark of the origin of speech. And in every silence there is something of the spoken word, as a long-lasting mark of the power of silence to create speech. Speech is therefore essentially related to silence.

Once a person starts speaking to another, he learns that speech no longer belongs to silence but to people. He learns it through the Thou of the other person, because through the Thou, the word now belongs to people and no longer to silence. When two people are conversing with each other, however, a third is always present: Silence is listening. This is what gives breadth to a conversation: When the words are not moving simply within the narrow space occupied by the two speakers, but come from far away, from the place where silence is listening. This gives the words a new fullness.

But not only that: The words are spoken as if from the silence, from that third person. And the listener receives more than the speaker himself is able to give. Silence is the third speaker in such a conversation.

- Authenticity