|

AGORA - Philosophical Topics Important thinkers on important life-issues |

- Attitudes

- Authenticity

- Death

- Philosophizing

- Friendship

- Beauty

- Happiness

- Inner Freedom

- Inner Truth

- Love

- Meaning

- Music

- Right & Wrong

- Romantic Love

- Sex

- Solitude

- Sublime

- The Other Person

This month's topic: DEATH

How should I live in the face of death?

WEEK 1 - Montaigne WEEK 2 - Lucretius WEEK 3 - Foss WEEK 4 - Camus WEEK 5 - Unamuno An issue for reflection

HOW SHOULD I LIVE IN THE FACE OF DEATH?

- What can philosophy say about death? Death is a fact, there is nothing to do about it. You must simply learn to live with the fact that you will die sooner or later!

- That’s one possibility.

- What do you mean? You must learn to accept it. Unless you prefer not to think about it and pretend that you will live forever.

- That’s another possibility.

- Or, unless you convince yourself in life after death. But that takes a lot of faith.

- That’s a third possibility.

- Or, of course, you may decide to be a romantic hero and look death straight in the eye – to be terrified in the name of truth and honesty.

- That’s a fourth possible answer.

- What are you talking about?

- Possible answers to the philosophical question: How should I live my life, knowing that I am going to die?

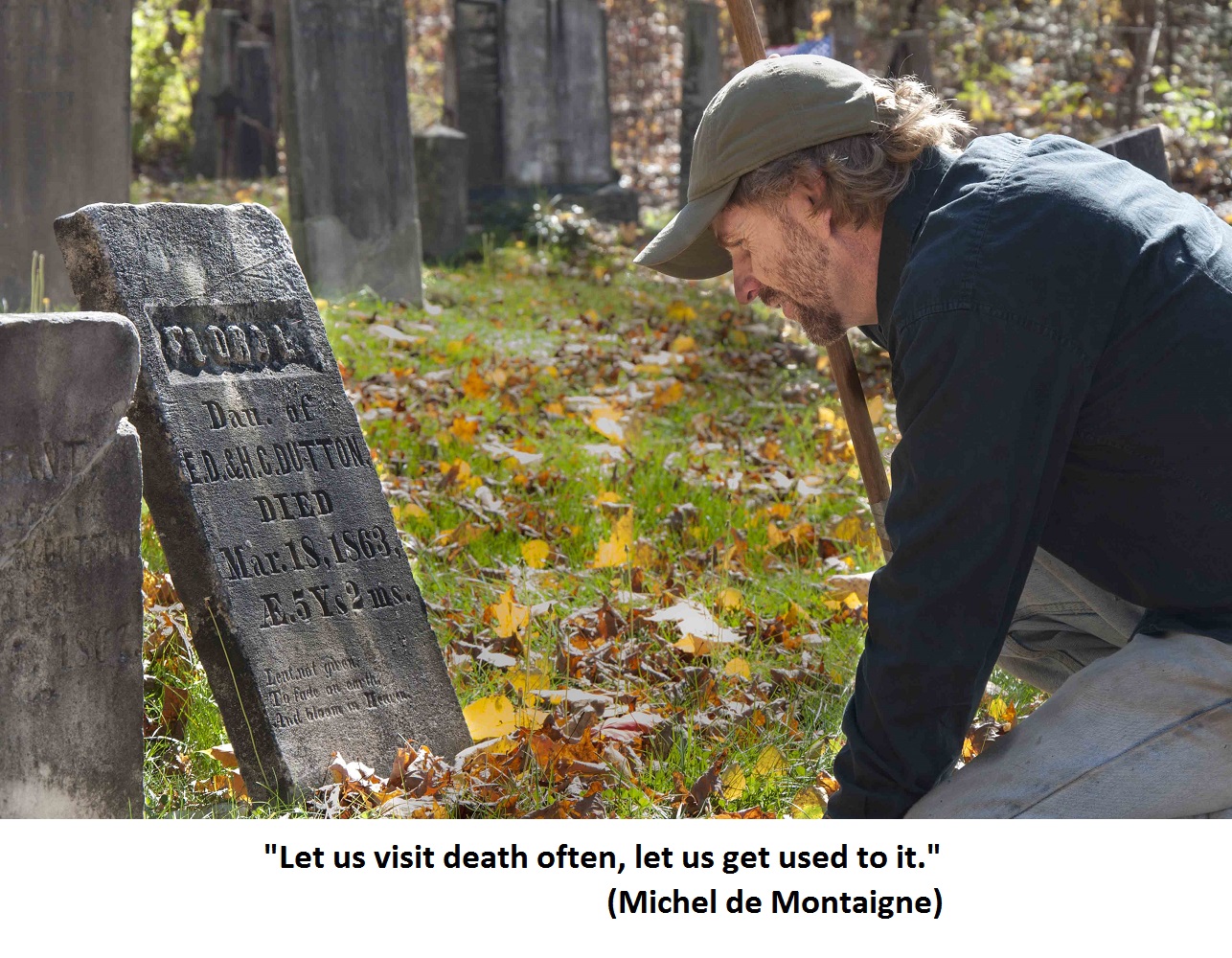

MICHEL de MONTAIGNE

Always prepare yourself to die

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) was an influential French philosopher of the Renaissance. He was born to a wealthy family in south-west France, where his father, Lord of Montaigne, devised for him a rich educational program at home. As a child he was brought up speaking Latin, which became his first language. He studied law at the University of Toulouse, and then served in various important political positions. In his early 30s he was forced by his family to marry. After the death of his father he became Lord of Montaigne, and at the age of 38 he retired to his family estate and started writing The Essays. After almost 10 years of seclusion, he left to travel in Europe, and on his return became the mayor of Bordeaux. He died of quinsy (abscess in the mouth) at the age of 59.

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) was an influential French philosopher of the Renaissance. He was born to a wealthy family in south-west France, where his father, Lord of Montaigne, devised for him a rich educational program at home. As a child he was brought up speaking Latin, which became his first language. He studied law at the University of Toulouse, and then served in various important political positions. In his early 30s he was forced by his family to marry. After the death of his father he became Lord of Montaigne, and at the age of 38 he retired to his family estate and started writing The Essays. After almost 10 years of seclusion, he left to travel in Europe, and on his return became the mayor of Bordeaux. He died of quinsy (abscess in the mouth) at the age of 59.

The following text is adapted from the essay “To philosophize is to learn how to die” from his major book The Essays, which he wrote and revised several times between 1571 and his death. This is a large collection of essays, written in a personal and conversational style, with many anecdotes, digressions, autobiographical notes, and quotations from ancient writers. Nevertheless, it also offers insightful and open-minded philosophical discussions, which had considerable influence on many writers and thinkers.

The end of our road is death. It is the necessary end-point we can see. And if it frightens us, then how can we make one step forward without anxiety? For ordinary people, the solution is not to think about death. But what stupidity can produce such a gross blindness? […] You might say: “But what does it matter what you do, as long as you avoid suffering?” I agree with that. If there was any way to avoid the blow of Death – even by crawling under the skin of a calf – I would not be ashamed to do it.[…]

But it is madness to think you can succeed this way. People come and go, they run and they dance, and never say a word about death. Everything is well and good. Yet, when death comes – to them, their wives, their children, their friends – and it catches them unprepared, then what storms of emotions overwhelm them! What cries, what anger, what despair! Have you ever seen anything so low, anything so changed, so confused? We must start preparing for it earlier. […] If death was an enemy which could be avoided, I would suggest being a coward. But this cannot be done. Death can catch a coward running away just as easily as an honorable person. No shield can protect you from it. We must learn to stand firm and fight it.

We must start preparing for it earlier. […] If death was an enemy which could be avoided, I would suggest being a coward. But this cannot be done. Death can catch a coward running away just as easily as an honorable person. No shield can protect you from it. We must learn to stand firm and fight it.

In order to remove the greatest advantage which death has over us, let us adopt a way that is contrary to the common way. Let us take away the strangeness of death. Let us visit death often, let us get used to it, let us have death in our minds more often than anything else. Every moment let us imagine all its aspects. Whenever a horse stumbles, or a tile falls from a building, or a needle pricks, let us at once think: “And if this was death?”

Let us brace ourselves and make an effort. In the middle of joy and parties, let us recall our human condition. Let us never allow pleasure to distract us and make us forget the many ways in which our joy is subject to death, and the many ways in which death threatens to snatch our joy away. […]

We don’t know where death is waiting for us, so let us wait for it everywhere. To practice death is to practice freedom. A person who has learned how to die has unlearned how to be a slave. […]

I myself am not so much melancholic as I am an idle dreamer. From the beginning, nothing concerned me more than thoughts about death, even in the most immodest period of my life. […] At first it seems impossible not to feel the sting of such ideas, but if you keep thinking them, you eventually tame them. No doubt about that. Otherwise, I would be in continual terror and agitation. […]

I am now ready to leave, thank God, whenever he pleases. I am untying my knots. I have already half-said my good-byes to everyone except myself. Nobody has ever prepared to leave the world more simply or fully than I have. No one has let go of everything more completely than I try to do. […]

I want Death to find me planting my vegetables, neither worrying about it nor about the unfinished gardening. I once saw a man dying who, until the last moment, kept complaining that destiny interrupted the history book he was writing, and he got only to our fifteenth or sixteenth king! We must throw away such feelings. They are harmful and vulgar.

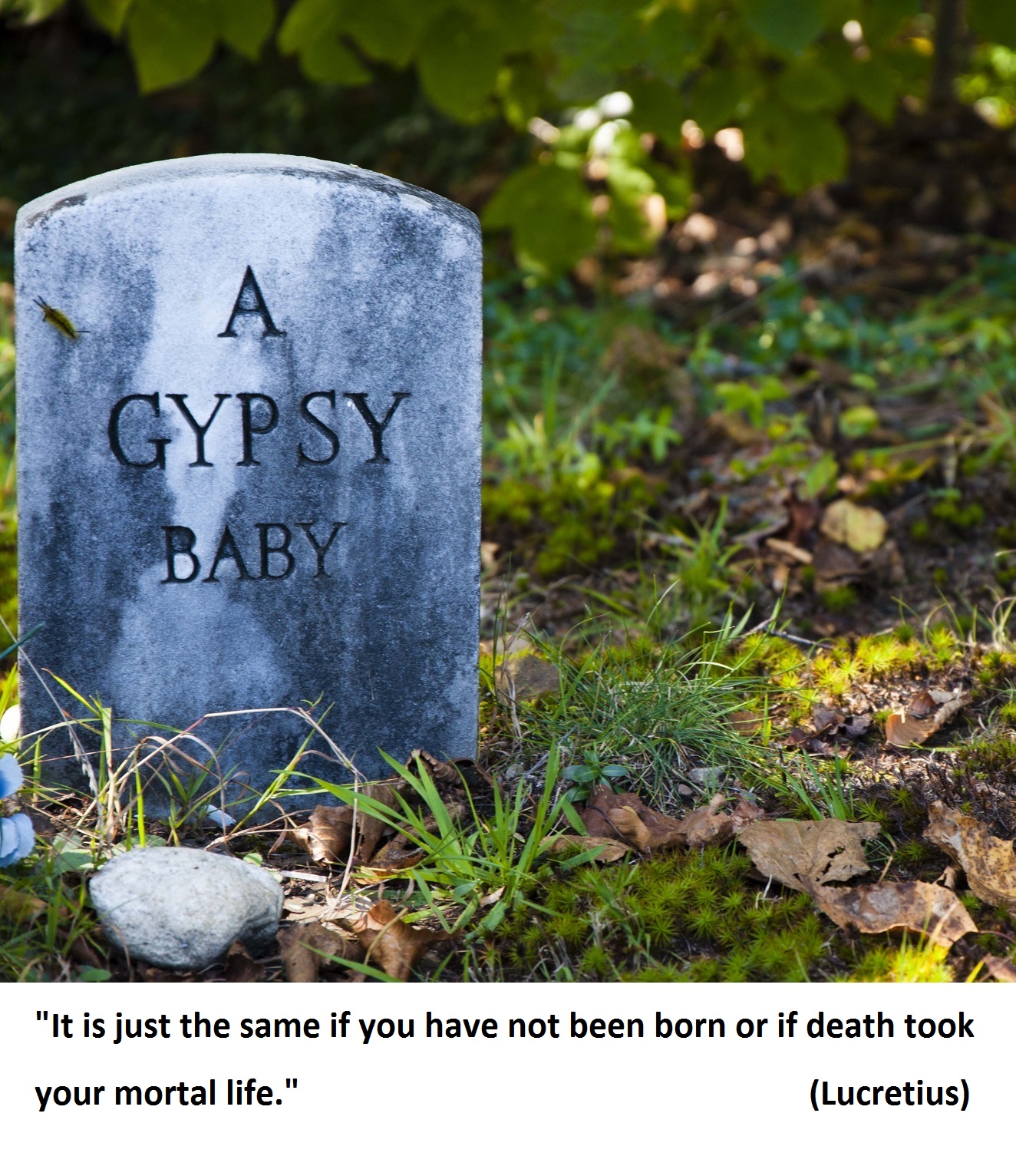

LUCRETIUS

It makes no sense to fear death

Lucretius (99 BC – 55 BC) was a Roman poet and philosopher who was influenced by Epicurean ideas. The only text we have from him is his book-long philosophical poem On the Nature of Things, which influenced later thinkers. Very little is known about his life, although there are some unreliable ancient stories about him.

Lucretius (99 BC – 55 BC) was a Roman poet and philosopher who was influenced by Epicurean ideas. The only text we have from him is his book-long philosophical poem On the Nature of Things, which influenced later thinkers. Very little is known about his life, although there are some unreliable ancient stories about him.

The following text is adapted from Book 3 of Lucretius’ On The Nature of Things (which consists of six books). Like Epicurus (to whom he dedicated this poem), he believed that the universe is physical, that the soul is physical too, and that there is no life after death. When the physical body and the physical soul separate, this is our end. Nevertheless, we should not be afraid of death, according to Lucretius, and for several reasons: First, in death we will be free from the distress of life. Also, death is not painful – after we die we will not feel anything bad. We will not even miss life or want to live again. Furthermore, our non-existence after death is not worse than our non-existence before our birth. We are afraid of death because we imagine ourselves seeing our destroyed body – but of course, after we die we will not be able to see our body. Therefore, our fear is based on false imagination.(Originally, the text was written in verses, as a poem. But to make it easier to read, we present it here as an essay.)

Death to us is nothing, and it doesn't concern us at all, because our mind is always mortal [and will disappear too]. Just as in the times before our death we felt nothing bad, even when there were terrible wars, […] similarly, when our body and soul will separate, nothing bad will happen to us – there will be no “us” anymore, nothing will make us feel anything.[…]

There is nothing in death which we should fear, there is no suffering for somebody who exists no more. It is just the same if you have not been born or if death took your mortal life.

Therefore, when you see a person crying that his body will rot after he dies, or that his body will be destroyed by fire or by animals, you should know well: He is not sincere. […] Because he doesn’t follow what he himself says or assumes: He fails to regard himself outside life and to erase his self from the world. He pretends that some part of him will still remain [to see himself]. He imagines himself alive and able to see his own dead body eaten by animals and torn by vultures. He pities his situation, but since he doesn't remove himself from the picture, he imagines seeing his body as if he stood beside it.

That’s why he cries for being mortal without noticing that in true death no “second self” will remain after death to worry that he is gone, or to lament that he is lying there mangled and burning.

[…]People say: “You will not be greeted anymore by a happy house and a wife who is the best, and your little children will not run up to you to receive their kisses, and your heart will not be touched with silent happiness. You will not hurry in your projects anymore and will not take care of your things.”

“Poor wretch,” so they say, “one bad hour took from you the many good things of life.” But they fail to add: “And you no longer have any desire to have these things”! If they could notice this and follow what this implies, they would free themselves from anxiety and fear.

[People say:] “Oh, you are now in the sleep of death and you will continue sleeping for the rest of time, released from every suffering. But we, we have wept for you without consolation, standing here by the awful fire which turns you into ashes. And our sorrow will never disappear from our heart.”

But mourner, what is the point of being sad and wasting yourself in grief, if, after all, the person is sleeping and resting? Because when his soul and body are sunk in sleep, he doesn’t demand to have his self back, and he doesn’t want to exist.

[…]

Look back: There was nothing for us during the eternal time before we were born. And nature holds this like a mirror of future times when we will be dead and gone.

What seems so horrible about it? What is there so sad about it all? Isn’t death much more peaceful than any sleep?

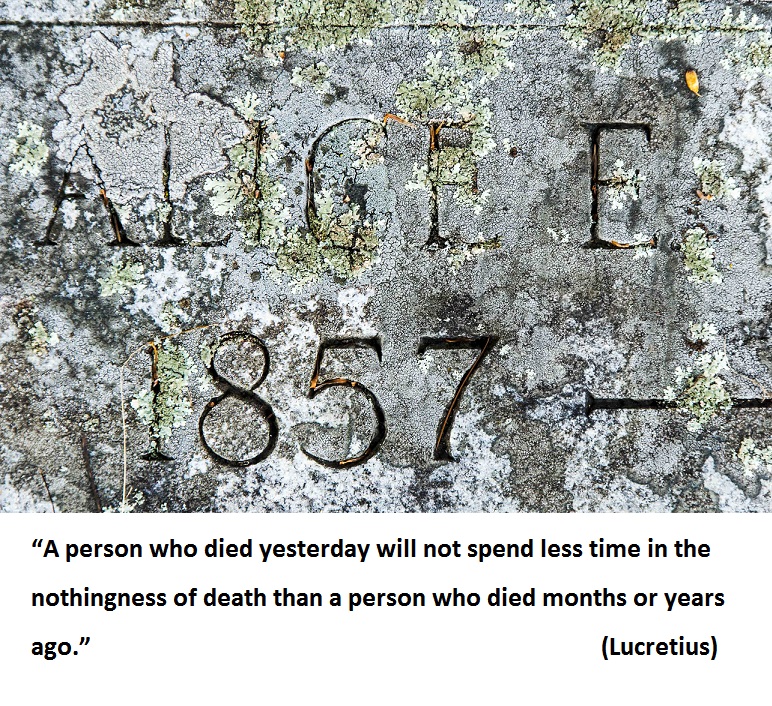

[…]

If we prolong life, we will not shorten the eternal time in which we will be dead. We cannot take off one single moment from the eternity in which we will be in a state of death.

Therefore, Oh man, by continuing to live as many generations as you may, eternal death will still be waiting for you. And a person who died yesterday will not spend less time in the nothingness of death than a person who died months or years ago.

MARTIN FOSS

Death as a sacrifice for a higher life

Martin Foss (1889-1968) was a German-born philosopher who is now often neglected. He was born in Berlin, and studied philosophy and law in Europe. Being Jewish, he left Germany after the rise of Hitler to power, and for four years traveled secretly between Paris and Berlin, working against the Nazis. He then moved with his family to the USA, with the help of the Quaker community, and taught philosophy at Harvard College and Temple University. He died of a heart attack at the age of 79.

The following text is adapted (and simplified in several places) from Foss’s book Death, Sacrifice, and Tragedy. Foss explains here that death is not an end. My death is part of the movement of my life towards a higher level of existence. And this movement does not end when I die, because my life is part of a larger movement.

To understand the text, it is important to see that Foss gives a special meaning to some concepts: SACRIFICE doesn’t mean simply risking myself. When I sacrifice, something dies in me for the sake of a higher level of life. In this sense, life is a constant sacrifice, because life is the movement towards a higher level.

My sacrifice is my response to my destiny. But DESTINY does not mean a fate that is imposed on me from heaven. It means, rather, a call which I receive from a higher life – a call which I am free to follow (or not to follow) in my own way.

This HIGHER LIFE (or higher sphere or meaning) is not a “thing” – it is not God, or heaven, or any fixed object. Rather, it is the horizons of life that are broader than my small ego. It includes me but also other people, and life in general. One might call it human reality, or Life, or the community of human beings.

My death, therefore, is part of a larger sacrificial movement in which I respond to a higher level of life and sacrifice myself to it.

From CHAPTER 6

No development occurs without the sorrow which accompanies the necessity to destroy in order to develop. The child in us, with his charm and innocence, is destroyed in order that the adolescent may appear. The adolescent, with his vivacity and daring, must be sacrificed in order that the adult may be born.

From CHAPTER 7

Sacrifice, even if it is death, is not an end but a transition to a new beginning. It is an offering which by passing away is somehow preserved because it integrates and intensifies the reality it was given to. In the sacrificial act, what is seemingly destroyed continues living. It is therefore not only preserved, but – more than that – it is elevated and it plays a role in a higher sphere of meaning. This is a destruction which turns into creation.

[…]

The death of the beloved, understood as his sublime offering and sacrifice in the communion and for it, will keep the communion between the survivor and the deceased. It will intensify the living experience of this communion, in which the deceased continues living. The death will not impoverish the survivor but will enrich him and send him on his way with greater courage. He will feel strengthened in the permanent presence of the sacrifice, which has always been the essence of the loving communion but which has now received its ultimate seal through the final and total offering.

[…]

It cannot be repeated too often that sacrifice is the conversion from loss into gain. It is not an end but a beginning. […] The meaning of death, experienced as an element of life, is its resurrection out of death.

From CHAPTER 9

Life is essentially a continuous conversion from a lower sphere to a higher one, destroying the lower for the sake of realizing the higher. Therefore, this creative destruction, this sacrificial action, gives to life its essential character, which is sacramental. It can be called “tragic.” Life in its maturity is a tragic drama because it cannot be lived without the continuous destruction of what is dear to us. Whether the object of destruction and sacrifice is bodily or mental, our past memories and achievements, it is always a part of ourselves which we must sacrifice. It is always self-sacrifice, and therefore it is accompanied by sorrow and suffering.

[…]

If we try to name the mysterious domain which calls us to sacrifice – this destiny, then we should be aware that any name will be inadequate. We may speak of the “community of lives” of which the person is a member. […] Such a communion of total and unlimited sharing is a communion of love or friendship, absolute and unique, not influenced by the ups and downs of everyday life, holier than any single life but giving dignity to the life which serves in it, responsible for the wider life of the communion. Thus, the call of destiny comes from an extended reality, a wider self than the individual self, but a reality to which the individual belongs as a member.

[…]

Sacrifice intensifies and enriches life. It is the price paid for our growing future and our growing strength. Intensification, too, goes beyond our ego, and it radiates into the life of the communion, sanctifying this wider life through the sacrificial act.

[…]

Even when death occurs, it is not the only sacrificial act, not even the ultimate one. It is rather only the final seal on the sacrificial destruction which has happened before. It leaves the person in a disturbed but intensified state of existence which is the result of a sacrifice throughout life.

ALBERT CAMUS

Revolt against the absurd death

Albert Camus (1913-1960) was an important French existentialist philosopher and novelist. He was born in French Algeria to poor parents and studied philosophy at the University of Algiers. He then moved to France, where he worked as a journalist in several newspapers. At different periods of his life he was associated with communist, anarchist, democratic, and human rights circles. He married twice, although he also had many extra-marital affairs. During World War II he joined the French resistance movement against Nazi occupation, but continued writing. In 1941 he published his first two books, The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus. In 1957 he received the Nobel Prize for literature. He died in a car accident at the age of 46.

Albert Camus (1913-1960) was an important French existentialist philosopher and novelist. He was born in French Algeria to poor parents and studied philosophy at the University of Algiers. He then moved to France, where he worked as a journalist in several newspapers. At different periods of his life he was associated with communist, anarchist, democratic, and human rights circles. He married twice, although he also had many extra-marital affairs. During World War II he joined the French resistance movement against Nazi occupation, but continued writing. In 1941 he published his first two books, The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus. In 1957 he received the Nobel Prize for literature. He died in a car accident at the age of 46.

The following text is adapted from Camus’ book Myth of Sisyphus (1941). Camus starts his discussion from simple, insignificant moments. In these “ridiculous beginnings,” we sometimes feel that our world is “absurd” – in other words, it offers us no meaning. This is primarily (although not only) because we are going to die. Life leads nowhere, and everything we do will be ended by death. Doctrines about heaven and the afterlife are not convincing; they are no more than abstract hypotheses. The appropriate response is not to ignore the absurd, not to despair and commit suicide, not to entertain baseless hopes for eternal life. On the contrary, the authentic person – the “absurd person” – revolts against the absurd and looks it straight in the eye. He lives with full awareness of the absurdity of life and of the approaching death.

From the chapter “ABSURD WALLS”

At any street corner, the feeling of absurdity can strike any person in the face. […] All great actions and all great thoughts have a ridiculous beginning. Great works are often born on a street corner or in the revolving doors of a restaurant. The same is with absurdity. The absurd world, more than other things, derives its nobility from that miserable birth. […]During every day of a monotonous life, time carries us. But a moment always comes when we have to carry it. We live on the future: “tomorrow,” “later on,” “after you establish yourself,” “you will understand when you are old enough.” Such irrelevancies are wonderful, because, after all, it is a matter of dying. Yet, a day comes when a person notices or says that he is thirty years old. Thus he asserts his youth. But at the same time, he situates himself in relation to time. He takes his place in it. He admits that he stands at a certain point on a time-curve and acknowledges that he has to travel to its end. He belongs to time, and through the horror that grabs him, he recognizes his worst enemy. Tomorrow – he was longing for tomorrow, whereas everything in him should reject it. This gut-feeling revolt is the absurd.

[…]

I come at last to death and to the attitude we have toward it. On this point everything has been said, and it is proper to avoid pathos. Yet, you can never be surprised enough that everyone lives as if nobody “knows” [that he is going to die sooner or later]. This is because in reality we do not experience death. Properly speaking, we experience nothing except for what we have lived and made conscious.

[…]

All the pretty speeches about the eternal soul will prove convincingly the opposite: From this motionless dead body, which doesn’t respond if you slap it, the soul has disappeared. This basic and conclusive fact of the adventure of life creates the absurd feeling. Under the fatal light of our destiny, its uselessness becomes evident. No values and no efforts are justifiable in the face of the cruel mathematics that dictates our condition.

From the chapter “PHILOSOPHICAL REASONING”

Living is keeping the absurd alive. Keeping it alive is above all contemplating it. Unlike Eurydice, the absurd dies only when we turn away from it. Revolt is, therefore, one of the only coherent philosophical positions. Revolt is a constant confrontation between a person and his own lack of understanding [of life]. It means insisting on an impossible transparency. It challenges the world every second again. […] This is not aspiration, because it is devoid of hope. This revolt means being sure of a crushing fate, without the resignation that should accompany it. […] The person sees his future, his unique and dreadful future, and he rushes toward it. In contrast, suicide, in its own way, settles the absurd. It covers up the absurd with death. But I know that in order to keep alive, the absurd cannot be settled. It escapes suicide if it is simultaneously awareness of death and rejection of death. It is, like in the last thought of a man condemned to die, that shoe-lace that despite everything he sees a few meters away, the moment before his dizzying fall.The revolt gives life its value. When it is spread out over the whole life-time, it restores the majesty of life.

[…]

The absurd is the extreme tension which the person maintains constantly by his own effort. Because he knows that through this awareness, and through this day-to-day revolt, he proves his only truth, which is defiance.

MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO

The After-Life - Absurd but necessary

Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936) was a Spanish philosopher, novelist and poet. After studying at the University of Madrid, he became a professor at the University of Salamanca, and then rector of the university. In 1924 Unamuno published articles criticizing the Spanish dictator Primo de Rivera, and as a result he was dismissed from the university and escaped to France. After the fall of Rivera, in 1930, Unamuno returned to Salamanca to become rector again. In 1936 he was again banished from the university, this time for criticizing Franco. He died from heart attack while under house arrest.

Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936) was a Spanish philosopher, novelist and poet. After studying at the University of Madrid, he became a professor at the University of Salamanca, and then rector of the university. In 1924 Unamuno published articles criticizing the Spanish dictator Primo de Rivera, and as a result he was dismissed from the university and escaped to France. After the fall of Rivera, in 1930, Unamuno returned to Salamanca to become rector again. In 1936 he was again banished from the university, this time for criticizing Franco. He died from heart attack while under house arrest.

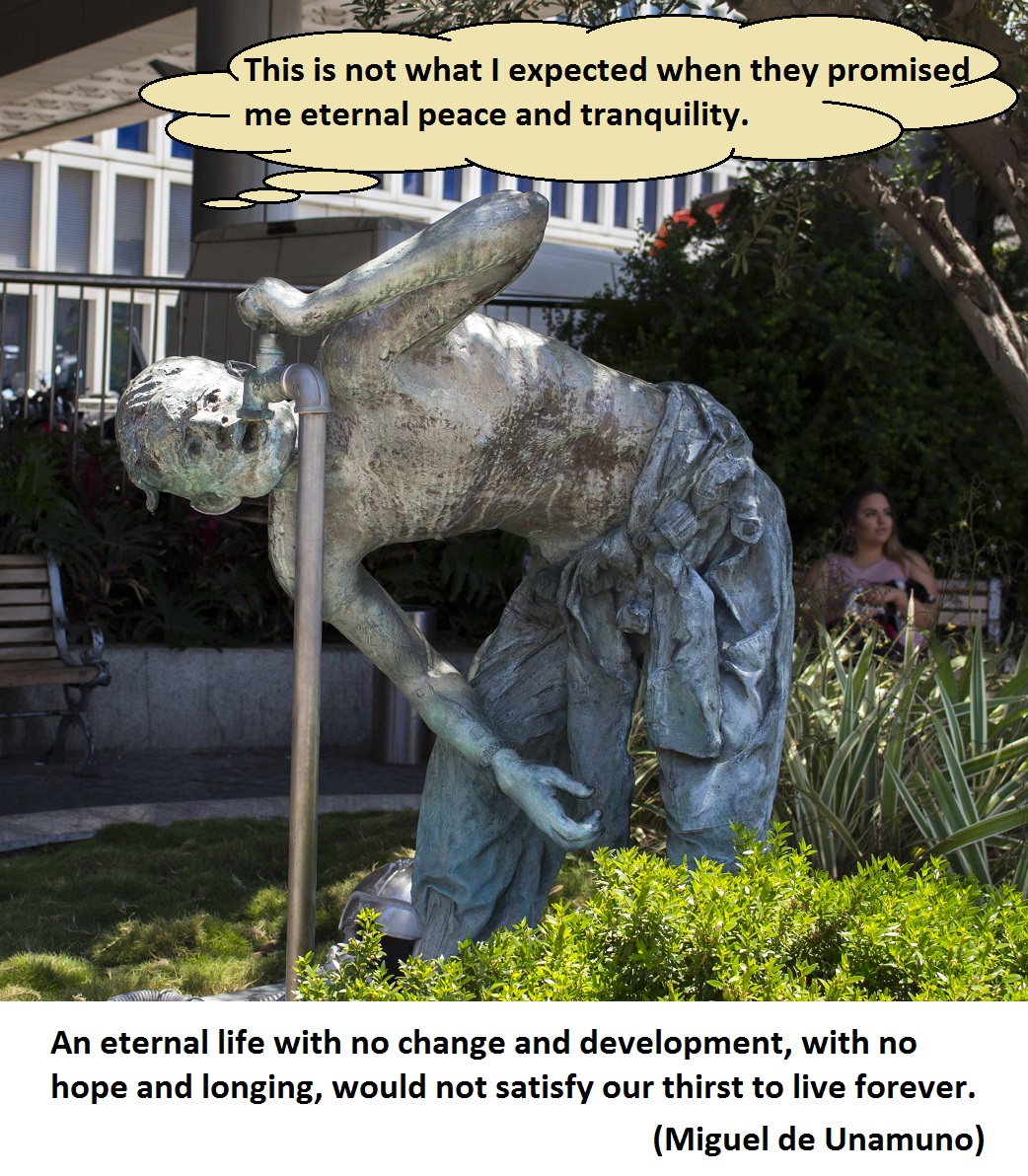

The following text is adapted from Unamuno’s major book The Tragic Sense of Life (1912). For Unamuno, the "tragic" is the struggle between life and reason. Reason is clear and precise, but it is remote from life. Our reason and our heart pull us in opposite directions, especially in the issue of death and immortality. We long for eternal life, but reason is unable to make sense of this longing. It cannot paint a coherent possibility that would satisfy our longing to live forever.

According to reason, after we die we may perhaps (who knows) be absorbed into a universal consciousness, or live in a permanent heaven with perfect happiness – but all this would not satisfy me. I want to continue to live as myself, as John Smith. I don’t want to lose my identity, to forget my struggles, or to remain frozen in an unchanging perfection. I want to continue to live forever as a person who develops, struggles, hopes.

Unamuno’s response to this tragedy – in other words, to this struggle between our heart and our reason – is to preserve this contradiction. In order to live, we must feel this tragic conflict, this anxiety of contradictions between life and reason. If we don’t feel it, we are not really living. We must continue to hope for eternal life – and even believe in it – but at the same time also feel the doubts that come from reason.

From CHAPTER 10

Paradise, according to many, is society, a more perfect society than the society of this world. It is human society that blends together into one person. […]

But […] what happens to each individual consciousness [after death]? What will happen to me [after I die], to this poor fragile I, to this I who is the slave of time and space, this I who (as reason tells me) is no more than a momentary accident, but whom I try to save by living and suffering and hoping and believing? […]

The soul, my soul at least, longs for something more: not to be absorbed, not to rest, not to be peaceful, not to be extinguished. It longs for an eternal approaching without any arriving. Its longing is never-ending, an unending hope that is eternally renewed and is never fulfilled or eliminated. Along with this longing, my soul feels an eternal lack and an eternal sorrow. This sorrow, this pain, allows my soul to always expand in consciousness and in longing. […] Our life is a hope which keeps changing into memory, which creates again hope. Let us live! An eternity which would be like an eternal present, without memory or hope, would be death. Ideas are like that, but humans do not live like that. […]

My soul longs, then, for an eternal Purgatory perhaps, instead of a Paradise: It seeks eternal ascent. If there is an end to all suffering, however pure and spiritualized, an end to all desire, then what makes the blessed souls continue living? If they do not suffer for God, how do they love Him? […] If no fountain of doubt is left for them, how could they avoid falling asleep?

In sum, if nothing of the soul’s deepest tragedy remains in paradise, then what kind of life is left? Is there any greater joy possible than to remember grief (and to remember means to feel it) in the time of happiness? Doesn’t the freed prisoner feel nostalgia for his prison? Doesn’t he miss his previous dreams of freedom?

[…]

We have just seen that when we try to give a concrete and conceivable shape to our primordial and fundamental longing for an eternal life – a life which is conscious of itself and of its personal individuality, the result is multiple absurdities, aesthetic, logical, and ethical. There is no way to understand the beatific vision without contradictions and inconsistencies.

And nevertheless…

And nevertheless, we must long for it, no matter how absurd it all seems. Moreover, we must also believe in it, in one way or another, in order to live at all. “In order to live,” I say, not “in order to understand the Universe.” We must believe, and to believe is to be religious.

[…]

Perhaps it is madness, a great madness, for us to try to penetrate the mysteries beyond the grave. Perhaps it is madness to want to impose the self-contradictory dreams of our imagination upon the dictates of healthy reason. Healthy reason tells us that nothing should be built without foundation, and that it is not only useless but self-destructive to fill with fantasies the void of the unknown. And yet…

We must believe in the other life, in the eternal life beyond the grave, and in an individual and personal life in which each one of us senses his own consciousness and senses that it joins all others in their consciousness within the Supreme Consciousness, in God. We must believe in that other life in order to live this life and endure it and give it meaning and purpose.

And above all, we must feel and act as if an endless continuation of our earthly life is reserved for us after death. And if, instead, our fate is nothingness, then let us not accept it as a just fate.

- Authenticity