|

AGORA - Philosophical Topics Important thinkers on important life-issues |

- Attitudes

- Authenticity

- Death

- Philosophizing

- Friendship

- Beauty

- Happiness

- Inner Freedom

- Inner Truth

- Love

- Meaning

- Music

- Right & Wrong

- Romantic Love

- Sex

- Solitude

- Sublime

- The Other Person

ON BEING AUTHENTIC

What does it mean to be true to myself?

WEEK 1 - HENRI BERGSON WEEK 2 - MARCUS AURELIUS WEEK 3 - J. J. ROUSSEAU WEEK 4- J. P. SARTRE

July's issue for reflection

WHAT DOES IT MEAN

TO BE TRUE TO MYSELF?“This man is so authentic!”

“That girl is fake, a phony!”

“I will not listen to them – I must be true to myself!”

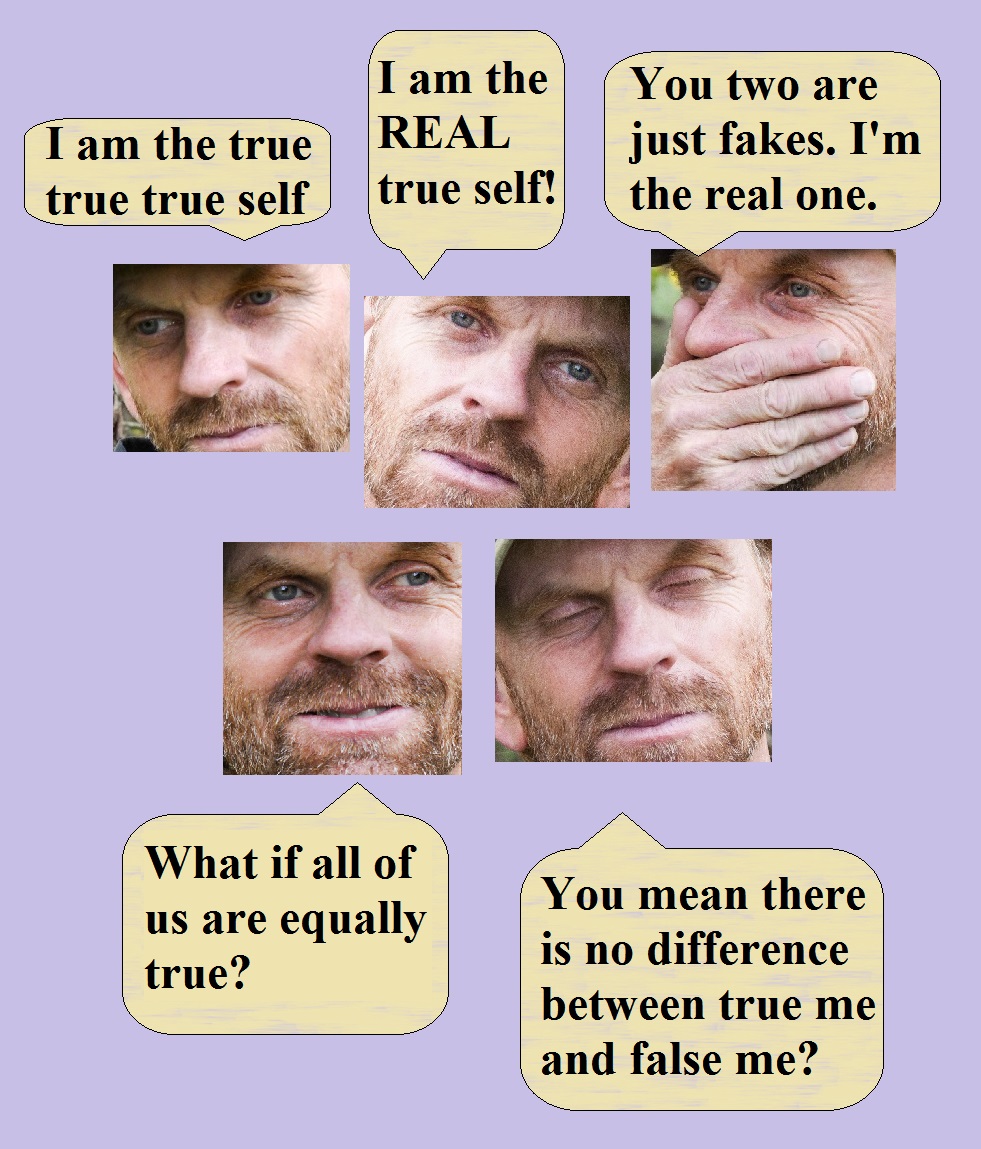

What does it mean to be authentic, or true to myself? Who should I be true to? Who do I betray when I am inauthentic, or fake? Who is my true “I”?

When I am true to myself, I am not true to everything I have – to my nose, or to my headache, or to my boredom. I am true to… to what? Who am I truly?

Perhaps my true self is natural, spntaneous energies within me, as the Swiss-French thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau said?

Or perhaps my true self is the rational part of myself, as the Roman philosopher Marcus Aurelius believed?

Or maybe there is no fixed self in me – I create myself again and again every moment, as the French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre explained?

Or maybe something else?

HENRI BERGSON

The true self as the holistic "symphony" within me

Henri Bergson (1859-1941) was an influential French philosopher, and a Nobel Prize winner in literature. He was born near Paris to a Jewish family, but as a teenager he lost his faith. He did his PhD in philosophy at the University of Paris, and his doctoral thesis was “Time and Free Will,” which was also his first major book. His works on laughter, psychology, biology, time, and other topics had a considerable impact in Europe and around the world, especially his book Creative Evolution (1907) which discusses the development of life on earth. He gave many lectures and communicated with major thinkers. After his retirement, in the 1930s, his popularity declined. In his last years he became sick and weak, and he died in Paris of Bronchitis at the age of 81.

Henri Bergson (1859-1941) was an influential French philosopher, and a Nobel Prize winner in literature. He was born near Paris to a Jewish family, but as a teenager he lost his faith. He did his PhD in philosophy at the University of Paris, and his doctoral thesis was “Time and Free Will,” which was also his first major book. His works on laughter, psychology, biology, time, and other topics had a considerable impact in Europe and around the world, especially his book Creative Evolution (1907) which discusses the development of life on earth. He gave many lectures and communicated with major thinkers. After his retirement, in the 1930s, his popularity declined. In his last years he became sick and weak, and he died in Paris of Bronchitis at the age of 81.

Bergson tells us that in everyday life we usually live on the surface of our being. We are normally aware only of our rigid, fixed ideas and emotions, which can be easily described and analyzed. But our inner life is much richer than it seems. Underneath this familiar surface, our inner life is a constant flow of infinite qualities and meanings, like a flowing symphony. This is our real being - a creative, free flow that includes our entire being.A central idea in Bergson’s philosophy is the idea of “duration.” Duration is the way life flows through time – it is a holistic and creative flow. It can be compared to a symphony: A symphony is one whole flow, not a collection of separate sounds one after each other or one next to each other. Each sound in the symphony “colors” the other sounds, and together they add up to one complete whole, one unitary movement. Likewise, duration (or the flow of life) is one whole flow, not a collection of separate moments or separate feelings. This flow is free and creative, because it gives birth to new surprising qualities.

However, when we analyze the flow of life, when we give names to feelings (“happy,” “anxious,” painful”), then we separate the flow into separate elements. Therefore, language and analysis create a layer of separate moments and separate qualities that are side by side.

The result is that our inner “symphony,” our inner duration, becomes covered with fixed ideas. Language creates a fixed layer of feelings that covers the depth of the self, just as dead leaves cover the flowing water. Therefore, we are usually not in touch with our deep self, which is a holistic symphony of our personal lives. Our lives are governed by the “dead leaves” – by fixed ideas, formulas, concepts. It is only in special moments that the real self, our inner duration, erupts through the dead leaves and appears on the surface.

In the following passages, adapted from his first book Time and Free Will, Bergson describes those special moments in which the true self - the "symphony" with us - comes up to the surface.

From Chapter 2

Our strongest beliefs are those which we find most difficult to explain, and to give reasons why we believe in them. In a certain sense, we have adopted them without any reason, because what makes them valuable for us is that they match the “color” of all our other ideas, and that from the very beginning we have regarded them as part of ourselves. [...] Each of these ideas is like a cell in an organism: everything which influences the whole self also influences the cell. But unlike a cell, which occupies a specific place in the organism, an idea which is truly ours fills our entire self.

Not all our ideas, however, are incorporated in this way in the flow of our consciousness. Many ideas float on the surface, like dead leaves on the water of a pond. The mind, when it examines them again and again, finds them always unchanged, as if they are external to the mind. Among these are the ideas which we receive ready-made — they remain in us without being properly assimilated. Or, the ideas which we have stopped to admire, and which have dried out in neglect.

The more we get away from the deeper strata of the self, the more our conscious states become separate items that can be counted, and that lie next to each other. Because these conscious states are more and more lifeless, more and more impersonal. Therefore, it is not surprising that we can adequately express in words only those ideas which least belong to us.

From Chapter 3

When our trustworthy friends advise us to take some important step, the sentiments which they express stay on the surface of our ego, and there they become solidified. Little by little they will form a thick crust which will cover up our own attitudes. We will believe that we are acting freely, but later on, when we look back, we will realize how much we were mistaken.

And then, just before we perform the act, something may revolt against it. It is the deep self rushing up to the surface. It is the outer crust bursting, suddenly surrendering to an irresistible push. In the depths of the self, below these very reasonable thoughts about very reasonable pieces of advice, something else was going on, a gradual heating and a sudden boiling over of feelings and ideas, not unperceived but unnoticed.[...]

We wish to know the reason why we have decided, and we find that we have decided without any reason, and perhaps against every reason. But sometimes this is the best reason. Because our action does not express some superficial idea, almost external to ourselves, separate and easy to explain. It agrees with the whole of our intimate feelings, thoughts and aspirations, it agrees with our particular conception of life which is the equivalent of all our past experience—in other words, with our personal idea of happiness and of integrity.

Here is one way to contemplate on this quotation

Sit quietly and read the text very slowly. Ask yourself: What does the text tell me? Listen to the words and let them speak in you. Notice phrases that attract your attention or touch you. When you finish reading the text two or three times, write down the phrases that touched you, and then summarize them in one sentence. You can now return to your daily activity, but keep this sentence in your mind for the rest of the day.

Marcus Aurelius

The true self as the rational self

Marcus Aurelius (121-180 AD) was a Philosopher and a Roman emperor from the Stoic school of philosophy. As a Stoic, he emphasized the importance of maintaining inner peace, accepting fate calmly, freedom from the power of emotions, and being in harmony with the cosmos. To do this, the Stoics believed, one has to be true to one’s rational faculty (as opposed to emotional forces) – also called one’s “guiding principle, “inner guide,” or "daemon," or as we would say today, true self.

Marcus Aurelius (121-180 AD) was a Philosopher and a Roman emperor from the Stoic school of philosophy. As a Stoic, he emphasized the importance of maintaining inner peace, accepting fate calmly, freedom from the power of emotions, and being in harmony with the cosmos. To do this, the Stoics believed, one has to be true to one’s rational faculty (as opposed to emotional forces) – also called one’s “guiding principle, “inner guide,” or "daemon," or as we would say today, true self.The following passages are from Marcus Aurelius' book Meditations, which was in fact a personal notebook where he wrote his personal reflections. The book tells us that the true self - "the guiding principle" or "the daemon" (sometimes translated as "the ruling faculty") is the rational faculty within the person. It is the element within us which follows Reason, which sees the larger perspective on things, thinks calmly, undisturbed by emotions, free from emotional attachment and the influence of others. When we follow this inner guide, we are true to our human nature, and are in harmony with the Logos that rules the Cosmos.

from BOOK 2

9. You must always bear in mind what is the nature of the whole cosmos, and what is my own nature, and how the first is related to the second, and what kind of a part I am in the whole. And there is nobody who stops you from always doing and saying the things that are according to the nature of the whole, of which you are a part.

17. Everything which belongs to the body is a stream, and what belongs to the soul is a dream and vapor, and life is a war and a foreigner's temporary visit, and after fame comes oblivion. What, then, can guide a person? One and only one thing – philosophy. But this consists in keeping the daemon within a person free from violence and unharmed, superior to pains and pleasures, doing nothing without purpose, without falsity or hypocrisy, without relying on anybody else to do or not to do anything. And also, accepting all that happens, and all that is assigned to you, as coming from wherever you yourself came. And, finally, waiting for death with a cheerful mind, accepting it as no more than a dissolution of the elements of which every living being is made.

from BOOK 7

16. The guiding principle does not disturb itself; it does not frighten itself or causes itself pain. [...] The guiding principle in itself desires nothing, unless it creates a desire for itself. Therefore, it is free from disturbance and is not stopped by anything, unless it disturbs or stops itself.

28. Retire into yourself. The rational principle which rules is by nature content with itself when it does what is just, and in doing so it achieves tranquility.

from BOOK 8

43. Different things delight different people. But it is my delight to keep the guiding principle sound without turning away either from any person or from any things that happen to people, but looking at, and accepting everything with welcome eyes, and using everything according to its value.

48. Remember that the guiding principle is invincible. When it is self-collected, it is satisfied with itself, if it does nothing which it does not choose to do [...] Therefore, the mind which is free from passions is a citadel, because a person has nothing more secure to which he can escape. Anybody who has not seen this is ignorant, but anybody who has seen it and does not escape to this refuge is unhappy.

from BOOK 9

15. Things stand outside us, as they are by themselves, neither knowing anything about themselves nor expressing any judgment. What is it, then, which passes judgment about them? The guiding principle.

22. Be quick to examine your own guiding principle, and the guiding principle of the universe, and that of your neighbor. Your own - so that you could make it right. That of the universe - so you would remember what you are a part of. And that of your neighbor - so that you would know whether he acted ignorantly or with knowledge, and so that you would remember that his guiding principle is similar to yours.

27. You have suffered infinite troubles by being dissatisfied with your guiding principle, when it does the things which it is made by nature to do. Enough of this.

Here is one way to reflect on this quotation

Read the text to make sure you understand it. Then ask yourself: "What does this text tell me personally? What does it tell me about myself?" Now start reading again the text, this time slowly, and listen to how the text responds to your quesion. Allow yourself to change the original words in order to make them more personally relevant to you.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The true self as the natural self

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) was born in Geneva and developed many of his philosophical views in Paris. His philosophy had a profound influence on modern political and social thought, and on education. His conception of the self and authenticity made an impact on our contemporary way of thinking.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) was born in Geneva and developed many of his philosophical views in Paris. His philosophy had a profound influence on modern political and social thought, and on education. His conception of the self and authenticity made an impact on our contemporary way of thinking.In his writings, Rousseau argues that a person has natural inner resources which are good. They are productive and creative, self-sufficient, simple, amiable, fair and just. This natural core is the true self, the original energies that motivate the person. To be authentic is therefore to be connected to one's natural self and to live form it. The problem is that society distorts us and disconnects us from our natural self, especially our social institutions and social norms. They make people become dependent on others, compare themselves to others, manipulate and pressure. As a result, people wear a false social mask which is alienated from their true nature.

The natural or authentic element in us is what we should value and develop. This, suggests Rousseau, can done with a proper education. This is an education which does not force foreign standards on the student, but cultivates the natural element in him.

The following texts are adapted from Rousseau’s famous book, Emile. In this book he illustrates his approach to education, using an imaginary example of an educator who raises and teaches a boy called Emile. The goal of the educator is to nourish the child’s natural tendencies and help them grow, while protecting them from negative social influences. The educator is, therefore, like a gardener who cares for a small tree, protecting it from negative external influences until it grows to be strong enough. His role is not to tell the tree which leaves to grow, but to supply it with the proper conditions - water, soil, sun - that would enable the plant to grow fully according to its nature. In Rousseau’s text, Emile grows up to become a man who behaves in a simple and direct way, a man who is self-sufficient and full of life, without pretense and falsity and excessive ambitions. This is a man whose behavior, thoughts and feelings come from his natural self.

From BOOK I: General Introduction

God makes all things good; man interferes with them and they become evil. He forces one soil to produce the products of another soil, one tree to bear the fruit of another tree. He confuses and mixes time, place, and natural conditions. He mutilates his dog, his horse, and his slave. He destroys and spoils all things. He loves everything that is deformed and monstrous. He is not satisfied with anything as nature made it, not even with man himself, who must learn his steps like a riding-horse, and be adjusted to his master's taste like the trees in his garden.

Yet, things would be worse without education, and mankind cannot be made by halves. Under existing conditions a man left to himself from birth would be, more than an educated person, like a monster. Prejudice, authority, necessity, bad examples, all the social conditions into which we are thrown, would suppress nature in him and put nothing instead. Nature would be like a small tree in the middle of the highway, bent this way and that way, and soon crushed by those who pass by.

I ask you, you can remove this young tree from the highway and protect it from the crushing force of social conventions. Take care of it and water it, or else it would die. One day its fruit will reward your care.

[...]

We are born weak, we need strength. We are helpless, we need aid. We are foolish, we need reason. All that we lack at birth, all that we need when we come to man's world, is the gift of education.

This education comes to us from nature, from people, or from things. From the education of nature comes the inner growth of our organs and faculties. From the education of men we learn how to use this growth. From the education of things we learn what we gain by our experience of our surroundings.

Fix your eyes on nature, follow the path traced by her. She keeps children at work, she hardens them by all kinds of difficulties, she quickly teaches them the meaning of pain and grief. […] This is nature's law; why contradict it? Don’t you see that in your efforts to improve its work you are destroying and wasting it? You think that it would be more dangerous to do from the outside what nature does from the inside. On the contrary, it is the way to prevent the danger.

From BOOK 4: Emile is an adolescent

After the general introduction about the principles of education, Rousseau goes on to illustrate them, using an imaginary pupil Emile, and his imaginary educator. Books 1-3 describe how the educator educates Emile so that he would be rooted in his natural self, and not in a social mask imposed on him from the outside. He follows Emile through the years as he grows, until he becomes an adolescent. Here Book 4 describes how Emile's education continues, and the kind of person Emile becomes.

It is not philosophers who know most about human beings. They only view them through the preconceived ideas of philosophy, and I know no one who is so prejudiced as philosophers. A savage would judge us more rationally. The philosopher is aware of his own defects, he is indignant at our defects, and he says to himself, "We are all bad alike.” The savage looks at us unmoved and says, "You are mad." He is right, because no one does evil for sake of evil. My pupil is that savage, with this difference: Emile has thought more, he has compared ideas, he has seen our errors closely, he is more on his guard against himself, and he only judges of what he knows.

[...]

Emile cares too little about the opinions of other people to value their prejudices. And he doesn’t care whether people respect him or not until they know him. His attitude is neither shy nor arrogant, but natural and sincere. He knows nothing about constraint or concealment, and he is just the same in a group of people as when he is alone. [...] He cannot bear to see anyone suffer. He will not give up his place to another person from mere external politeness, but he will willingly give it out of kindness. [...] He doesn’t flatter or agree. He says his opinion without arguing with others, because he loves liberty above all things. [...]

He says little, because he is not anxious to attract attention. For the same reason he only says what is to the point. [...] His heart is tender and sensitive, but he doesn’t care about popular opinion, although he loves to give pleasure to others. [...] For the same reasons he will never be careless about his manners or his clothes. [...]

He knows how he should seek his own happiness in life, and how he can contribute to the happiness of others. His sphere of knowledge is restricted to what is profitable. His path is narrow and clearly defined. [...] Emile is a man of common sense and he has no desire to be anything more.

Jean-Paul Sartre

My true self is my freedom to define myself

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) was an important French existentialist philosopher, political activist, novelist and playwright. In his student years, while studying philosophy and other fields at École Normale Supérieure, he met Simone de Beauvoir, who became his life-long companion and lover. The two maintained an ongoing open relationship, and developed philosophies that were close in spirit. In World War II Sartre was drafted by the French army, and was take a prison by German forces. On his return to Paris, he participated with other intellectuals in underground activities, and also published his main philosophical book Being and Nothingness (1943). At different times in his life he was actively involved in various social causes such as communism, anti-colonialism, and human rights. In 1964 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature, but declined it. He died in 1980 from a lung condition.

A fundamental idea in Sartre's philosophy is that human consciousness is radically free – there is no fixed human nature that determines how we behave. Our decisions are not determined by emotions, personality, or any other force. One may say that there is no “true self” within us. To be authentic can only mean being faithful to our freedom to determine what we do and who we are. The following quotations are adapted from a short but influential book, published in 1946. In this essay, Sartre explains the basic principles of his existentialist theory, and defends it against criticisms.

Atheistic existentialism, of which I am a representative, declares that if God does not exist, then there is at least one being whose existence comes before its essence, in other words, a being which exists before it can be defined by any conception of it. That being is the human being.

What do we mean by saying that EXISTENCE PRECEDES ESSENCE? We mean that the human being first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world – and defines himself afterwards. The human being, as seen by the existentialist, cannot be defined because at first he is nothing. He will not be anything until later, and then he will be what he makes of himself.

Thus, there is no human nature, because there is no God who can have a conception of it. A human being simply is. The point is not that he is simply what he conceives himself to be, but that he is what he wills to be after his leap towards existence. A human being is nothing else but what he makes of himself. That is the first principle of existentialism.

[…] What we mean to say is that the human being has a greater dignity than a stone or a table. Because he first of all exists – he is something which pushes itself towards a future, and he is aware that this is what he is doing. A human being is, indeed, a project which has a subjective life, instead of being a kind of moss, or a fungus or a cauliflower. Before he project himself, nothing exists; not even in the heaven of intelligence: A human being will only attain existence when he is what he decides to be.

[…] What we mean to say is that the human being has a greater dignity than a stone or a table. Because he first of all exists – he is something which pushes itself towards a future, and he is aware that this is what he is doing. A human being is, indeed, a project which has a subjective life, instead of being a kind of moss, or a fungus or a cauliflower. Before he project himself, nothing exists; not even in the heaven of intelligence: A human being will only attain existence when he is what he decides to be.[…] If it is true that existence is before essence, then a human being is responsible for what he is. Thus, the first result of existentialism is that it puts every human being in possession of himself as he is, and places the entire responsibility for his existence directly upon his own shoulders.

If indeed existence precedes essence, one will never be able to explain one’s action as a result of a given human nature. In other words, there is no determinism – man is free, man IS freedom. That is what I mean when I say that the human being is condemned to be free. Condemned, because he did not create himself, and yet he is at liberty. So from the moment that he is thrown into this world, he is responsible for everything he does.

The existentialist does not believe in the power of emotion. He will never regard a grand emotion as a destructive flow which forces the person to do certain actions, as by fate, and which, therefore, is an excuse for doing those actions. He thinks that the human being is responsible for his emotion.

Neither will an existentialist think that a person can find help through some sign that will be given to him upon earth to show him the right way – because the person himself interprets the sign as he chooses. He thinks that every person, without any support or help whatever, is condemned at every moment to invent man.

IS THE BIRD INAUTHENTIC FOR WANTING TO HAVE ARTIFICIAL FEATHERS, OR IS IT AUTHENTIC BECAUSE IT WANTS TO HAVE LARGE FEATHERS AND FLY AWAY FREELY? {youtube}CJIUNNssSVg{/youtube}

Thinking with others: THE PHILOSOPHICAL COMPANIONSHIP

Now that you are familiar with the issue of authenticity, you can reflect about it in the company of your friends, whether online or face-to-face. There are different ways of running such a group. It can be a reading group which discusses a short text, or a discussion group about a specific case-study, perhaps from the literature or the cinema. But an especially powerful way of doing it is in the "Contemplative Companionship."

In a Contemplative Companionship, the participants don't argue with each other. They don't speak from their opinions, but from their heart, from their deep self - in togetherness with the others. Like a group of musicians creating music together, they create a philosophical symphony together.

Here is a video-recording of a contemplative companionship with several Agora team-members. {youtube}CJIUNNssSVg{/youtube}

If you decide to start your own contemplative companionship, we invite you send us the results!

- Authenticity