|

AGORA - Philosophical Topics Important thinkers on important life-issues |

- Attitudes

- Authenticity

- Death

- Philosophizing

- Friendship

- Beauty

- Happiness

- Inner Freedom

- Inner Truth

- Love

- Meaning

- Music

- Right & Wrong

- Romantic Love

- Sex

- Solitude

- Sublime

- The Other Person

This month's topic: SOLITUDE

What is the value of solitude?

WEEK 1 - Powys WEEK 2 - Zimmermann WEEK 3 - Marias WEEK 4 - Kierkegaard WEEK 5 - Montaigne An issue for reflection

WHAT IS THE VALUE OF SOLITUDE ?- I am going away for several weeks. I need some solitude.

- Solitude?! Why would anybody choose to be lonely?

- Is SOLITUDE not the same as LONELINESS?

- Mmm… Maybe not. Solitude is being alone, far from people. But this doesn’t mean that you feel lonely.

- Exactly. Loneliness is a feeling: You feel disconnected, abandoned, sad. But you can be alone, in solitude, without feeling lonely.

- I see. So being alone and being lonely are not the same. I sometimes feel lonely even in the middle of a crowd of people.

- And I am sometimes alone without feeling lonely. On the contrary, I feel liberated and peaceful.

- So is solitude a good thing?

- A good question. I am going to find out

Inner Solitude

John Cowper Powys (1872-1963) was a British thinker, lecturer, novelist, literary critic, and poet. He was born to a family with several poets and writers, and studied at the University of Cambridge. In his mid-twenties he moved to the United States, and became known as an exceptionally charismatic speaker. He communicated with important intellectual figures and wrote philosophical essays, as well as novels. His first successful book which made him famous was Wolf Solent, a uniquely intense and poetic novel. In 1934, in his sixties, he returned to England, and then moved to Wales, continuing to write until his death.

John Cowper Powys (1872-1963) was a British thinker, lecturer, novelist, literary critic, and poet. He was born to a family with several poets and writers, and studied at the University of Cambridge. In his mid-twenties he moved to the United States, and became known as an exceptionally charismatic speaker. He communicated with important intellectual figures and wrote philosophical essays, as well as novels. His first successful book which made him famous was Wolf Solent, a uniquely intense and poetic novel. In 1934, in his sixties, he returned to England, and then moved to Wales, continuing to write until his death.From Chapter 2: “The Self Isolated”

Every human being is alone in the core of the mind. When we are born we cry, and that cry is the cry of loneliness. Thus it is with children. Thus it is with the growing youth. And the older we grow, the lonelier we grow. The smartest advice which one soul can give to another is to accept this law of nature. Yes, we must accept it, and not only accept it – but also find our unique happiness in it!

[…]

Our lonely ego is always enclosed by our own body, and very often by the intrusive and aggressive bodies around us. The life of our soul is cruelly dependent upon our bodily health, upon our burdened and exhausted sense perceptions. But the fact that every conscious self possesses a central core, a unifying force, an integral identity, the fact that it never loses the feeling of such an identity, implies a constant renewal of our inborn solitude. It implies our inherent isolation from the security of our sight, smell, taste, hearing, touch, and the overpowering pressure of other personalities. Because this central power is not only the mind, the psyche, the self, the ego – it is also the driving force, the energy, the will, the magnetic nucleus of our personality. […]

The self is so involved with the body that its main activity seems to be unifying and focusing our sense perceptions. And yet, there come moments when this central power within us seems to withdraw into some mysterious and remote levels of its own being, and we feel as if we approach the verge of strange and startling possibilities.This is only a feeling, but it represents an unquestionable fact: the fact that we possess a centralizing, unifying self or ego, which is the driving-force of everything we think, or do, or feel, or say. And whatever may be happening to our body, this self or ego, the conscious “I am I” within us, is absolutely alone. It is alone from the first moment of its awareness of life to its last moment on the threshold of what may be its final extinction.

[…]

The isolation of the self gives us the habit of contemplating at every moment the wide realms of our world. It enables us to feel the wind of outer space blow across the surface of our earth as we ride with it through the eternal ether. It gives a dignity, a beauty, a high and tragic significance to every phenomenon of mortal life. Everywhere it destroys dullness. Everywhere it kills the routine. Everywhere it touches with a natural, poetic tenderness the ultimate conditions of our existence on this earth.

People can acquire rosy cheeks, sparkling eyes, lively laughter, while they pursue pleasure in their groups and in their crowds; but it is only in solitude that they can come to know the happiness that is like the delight which children get from nothing at all.

There are many modern thinkers who emphasize the individual’s dependence upon society. But in fact, only the cultivation of interior solitude, when we are among crowded lives, makes society tolerable.

Those who live in internal solitude cannot be recognized when they go here and there among others. You cannot recognize them in street-cars, in trains, on pavements, in subways, in shops, in offices, in factories, in theatres, in warehouses. But their will-power lives stubbornly in their souls. Their ironic detachment cannot be violated.

[…]

Only when the soul is alone can the magic of the universe flow through it. The soul needs silence to hear the whispers of the long centuries, to feel the mystery of the cosmic evolution. It can attain this silence in the wildest commotion of the most crowded city. Material noises and shouts cannot interfere with it. What destroys this silence are the popular thoughts of the crowd, the vulgar thoughts that are no-thoughts. Life is full of mysterious presences traveling here and there, presences that are god-like. But these presences can only be caught in their airy journeys by minds that have learned the secret of being alone. To converse with the gods you must become as the gods. And this means that you must cultivate loneliness.

Solitude elevates the mind

Johann Georg Ritter von Zimmermann (1728-1795) was a Swiss philosopher and medical doctor. He was born to a noble family, studied at the University of Bern, and received his medical degree from the University of Gottingen in Germany. As a young man he published several books that became popular and widely read throughout Europe. He soon became the doctor of kings and nobles such as George III and Frederick the Great. Later in his life, however, he was engaged in religious and personal disputes, and had a number of enemies. He died at the age of 67 after months of mental and physical deterioration.

Johann Georg Ritter von Zimmermann (1728-1795) was a Swiss philosopher and medical doctor. He was born to a noble family, studied at the University of Bern, and received his medical degree from the University of Gottingen in Germany. As a young man he published several books that became popular and widely read throughout Europe. He soon became the doctor of kings and nobles such as George III and Frederick the Great. Later in his life, however, he was engaged in religious and personal disputes, and had a number of enemies. He died at the age of 67 after months of mental and physical deterioration.Zimmermann’s book Solitude was written after he married his second wife (the first died earlier), who was 30 years younger than him. Its four volumes were published between 1784-1786. Each chapter in the book discusses solitude from a different perspective: Its positive influence on the mind, on the heart, in retirement, in exile, at old age, and so on. The following text is slightly adapted from Chapter 2 of Volume 1, which deals with the influence of solitude on the mind.

Chapter 2

The love of solitude, when cultivated in the morning of life, elevates the mind to a noble independence. However, to acquire the advantages of solitude, the mind must not be driven to it by melancholy and dissatisfaction, but rather motivated by a real dislike of the idle pleasures of the world, a rational contempt for the deceitful enjoyments of life, and an objective worry not to be corrupted and seduced by the world’s clever and destructive delights.

[…]

The advantages of solitude, to a mind that feels a real disgust for the dull activities of society, are great. When we are freed from the world, the veil which obscured the intellect suddenly falls, the clouds which dimmed the light of reason disappear, the painful burden which oppressed the soul is alleviated. We no longer struggle with surrounding dangers, the fear of danger vanishes, the sense of misfortune becomes softened. What happens to us no longer produces the murmur of dissatisfaction, and we enjoy the delightful pleasures of a calm, tranquil, and happy mind. Patience and resignation follow, and they reside in a happy heart. Every destructive worry flies away on the wings of joy, and everywhere we see pleasant and interesting scenes: the brilliant sun sinking behind the lofty mountains and coloring their snowy peaks with golden rays; the choir of birds seeking a secure place to rest; the sound of the amorous rooster; the solemn and dignified march of bulls returning from their daily work; and the graceful steps of the generous horse. When we are in the midst of the vicious pleasures of a great metropolis – where wisdom and truth are constantly despised, and integrity and conscience are thrown aside as inconvenient and oppressive – the best ideals are obscured, and the purest virtues of the heart are corrupted.

But the most unquestionable advantage of solitude is that it accustoms the mind to think. The imagination becomes more vivid, and the memory more faithful, while the senses remain undisturbed, and no external object agitates the soul. When we are far from the tiresome tumults of public society, where all kinds of objects dance before our eyes and fill the mind with incoherent ideas, we learn to focus our attention on a single subject, and to contemplate it alone.

[…]

Profound meditation in solitude and silence often elevates the mind above its natural zone. It fires the imagination and produces the most refine and sublime ideas. The soul then tastes the purest and most refined delight, and it almost loses the idea of existence in the intellectual pleasure it receives. The mind on every emotion flies through space into eternity. It is raised, in this free enjoyment of its powers by its own enthusiasm, and strengthens itself in the practice of contemplating the noblest topics, and of adopting the most heroic pursuits.

[…]

Solitude refines the taste, by giving the mind greater opportunities to select the beauties of those objects which attract its attention. There it depends only on us to choose those activities which afford the highest pleasure, and to read those writings and reflections which purify the mind, and remember them with the richest variety of images. In solitude we easily avoid the false ideas which we acquire so easily in the social world, where we rely on the preferences of others instead of consulting our own. It is intolerable to be forced continually to say, “I don’t dare to think otherwise.” Why, alas, shouldn’t people strive to form their own opinions, instead of letting themselves be guided by the arbitrary dictates of others? If a work please me, why should it matter to me whether high society approves of it or not? What information do I receive from you, you cold and miserable critics? Does your approval make me feel what is truly noble, great, and good, with higher joy, or more refined delight? How can I submit to the judgment of people who always examine hastily, and generally judge wrongly?

Solitude as a form of "being with"

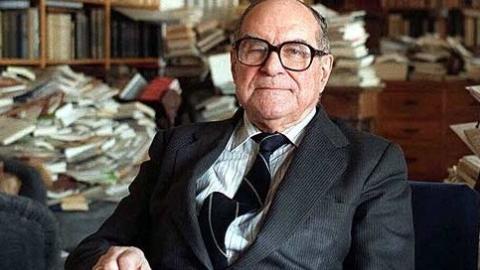

Julián Marías (1914-2005) was a Spanish philosopher, a student of Ortega y Gasset, and a major thinker of the so-called Madrid School. The Spanish Civil War interrupted his philosophy studies at Complutence University of Madrid, and after the war his PhD thesis was rejected because of his criticism of the dictator Franco. He was imprisoned for several months, and was released thanks to the intervention of several public figures. He was, however, banned from teaching for more than 30 years. As a result, he visited USA several times where he gave philosophy courses in important universities. He also founded, together with his teacher Ortega y Gasset, the Institute of Humanities.

Julián Marías (1914-2005) was a Spanish philosopher, a student of Ortega y Gasset, and a major thinker of the so-called Madrid School. The Spanish Civil War interrupted his philosophy studies at Complutence University of Madrid, and after the war his PhD thesis was rejected because of his criticism of the dictator Franco. He was imprisoned for several months, and was released thanks to the intervention of several public figures. He was, however, banned from teaching for more than 30 years. As a result, he visited USA several times where he gave philosophy courses in important universities. He also founded, together with his teacher Ortega y Gasset, the Institute of Humanities. Marías’ philosophy focuses on real life-situations. The foundation of philosophy, for him, is the real life of human beings, and philosophy investigates and systematizes the root of human existence as it is lived in real situations.

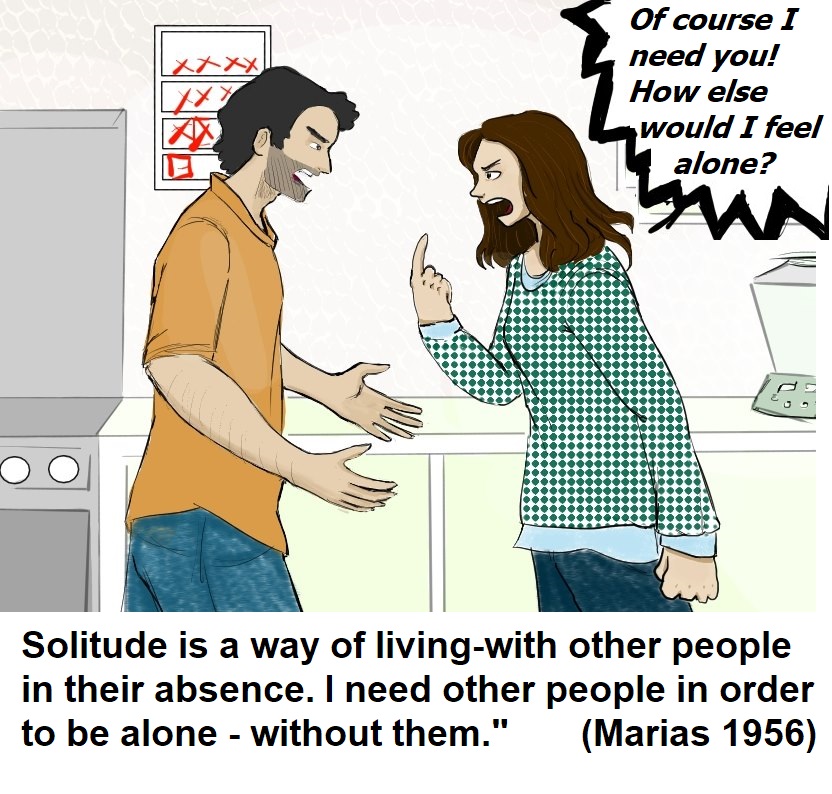

The following text is taken from Chapter 7 of Marías’ book Reason and Life (1956). Here Marías argues that a fundamental characteristic of human life is “living with”: Human beings are not individual atoms, but are essentially “with” other human beings. Even when I am in solitude, I am “with” others who are absent. In contrast, a stone or a chair cannot be “with” other things, and cannot be in solitude. Thus, solitude is a form of “being with” – being with nobody.

To live is, for the human being, both to be in the world and live with others: Two essential modes of “being with.” This means that a person’s world – in the deepest sense of the term – is double, containing both nature and society. But it is not enough to say that my circumstance includes, in addition to other “things” also other human beings, because that would make human beings just another part of nature. The important point is that these people function differently, as centers of other lives, of the circumstances that are mine too.

In other words, I encounter in my circumstance from the very beginning other people, who likewise encounter me, and who take me into consideration just as I do with them. Therefore, I take them into consideration in a peculiar way, which includes taking into consideration how they take me into consideration. Therefore, our reciprocal attitudes is very different from the way I relate to “things,” because, although I am with things, things are not, strictly speaking, with me. For this reason, things lack, even when they are in contact with me most directly, the proximity that makes other people my neighbors.

This situation, which goes far beyond mere co-existence, is what we call LIVING WITH. […] Living-with is not something added to the life of the individual, but one of its primary modes, on the same level as its localization in space, its temporality, or its being immersed in its physical surroundings. One might object that a person can be alone, but apart from the fact that this is not strictly true, it proves the fundamental character of living-with. Because only a creature whose nature consists of being accompanied can be alone. A stone is not, and cannot be, alone. Solitude is not a real “property” or “quality” – being alone is not like being seated, or being tired, or being asleep. To be alone means to be WITHOUT SOMEBODY. Solitude is a mode of living-with other people, in the concrete mode of absence, and it is, therefore, an actual lack. To use a paradox: I need other people in order to be alone – without them.

But at this point we must be very cautious because we may fall into a number of errors, in particular two. The first of these would be to believe that living-with is something secondary to individual life, so that individuals exist each one by himself, and then they can join together, or associate with one another, in order to achieve some purpose. In that case, living-with would be something derived, and it would be perfectly reducible to individual human reality.

[…]

The fact is that human life, which contains the dimension of living-with, has two possibilities within this living-with: solitude and company. In both of these cases, other people appear, although in different ways: as present or absent. I am with other people, or alone with other people. But since eventually my life is MINE – it is what I do and what happens to me, and nobody can take my place or share with me my actions, which determine what I am going to be at each moment – my life’s deepest root is solitude. And every company is, in reality, an attempt – culminating in friendship and in love – to merge two solitudes.

SØREN KIERKEGAARD

Solitude as an escape from oneself

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) was a Danish philosopher and one of the two “fathers” of existentialism (the other one being Friedrich Nietzsche). He was born in Copenhagen to a wealthy family and lived there most of his life in relative loneliness. His criticism of society and organized religion angered many people and alienated them. He died in a hospital from medical complications at the age of 42. His works became famous only in the 1920s, and they have been very influential ever since.

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) was a Danish philosopher and one of the two “fathers” of existentialism (the other one being Friedrich Nietzsche). He was born in Copenhagen to a wealthy family and lived there most of his life in relative loneliness. His criticism of society and organized religion angered many people and alienated them. He died in a hospital from medical complications at the age of 42. His works became famous only in the 1920s, and they have been very influential ever since. Kierkegaard’s extensive writings revolve primarily around the issue of how to live truly or authentically (or how to be a Christian, as he sometimes phrases it). For him, living truly means living with one’s entire being, with passion and commitment and faith. Most people, however, live a dull life of self-deception, so they do not really live.

The following text is adapted from Kierkegaard’s book Sickness unto Death, published in 1849. Here Kierkegaard discusses what he calls “despair,” which is a state in which one is disconnected from the eternal, or God, and thus loses one’s own self. Often the individual is not aware of his situation, which means that he is not aware of his own despair. Despair is therefore like a sickness which the sick person may or may not be aware of. Kierkegaard distinguishes between three kinds of despair: Despair that comes from ignorance of one’s self, despair that comes weakness and inability to accept one’s self, and despair that comes out of defiance.

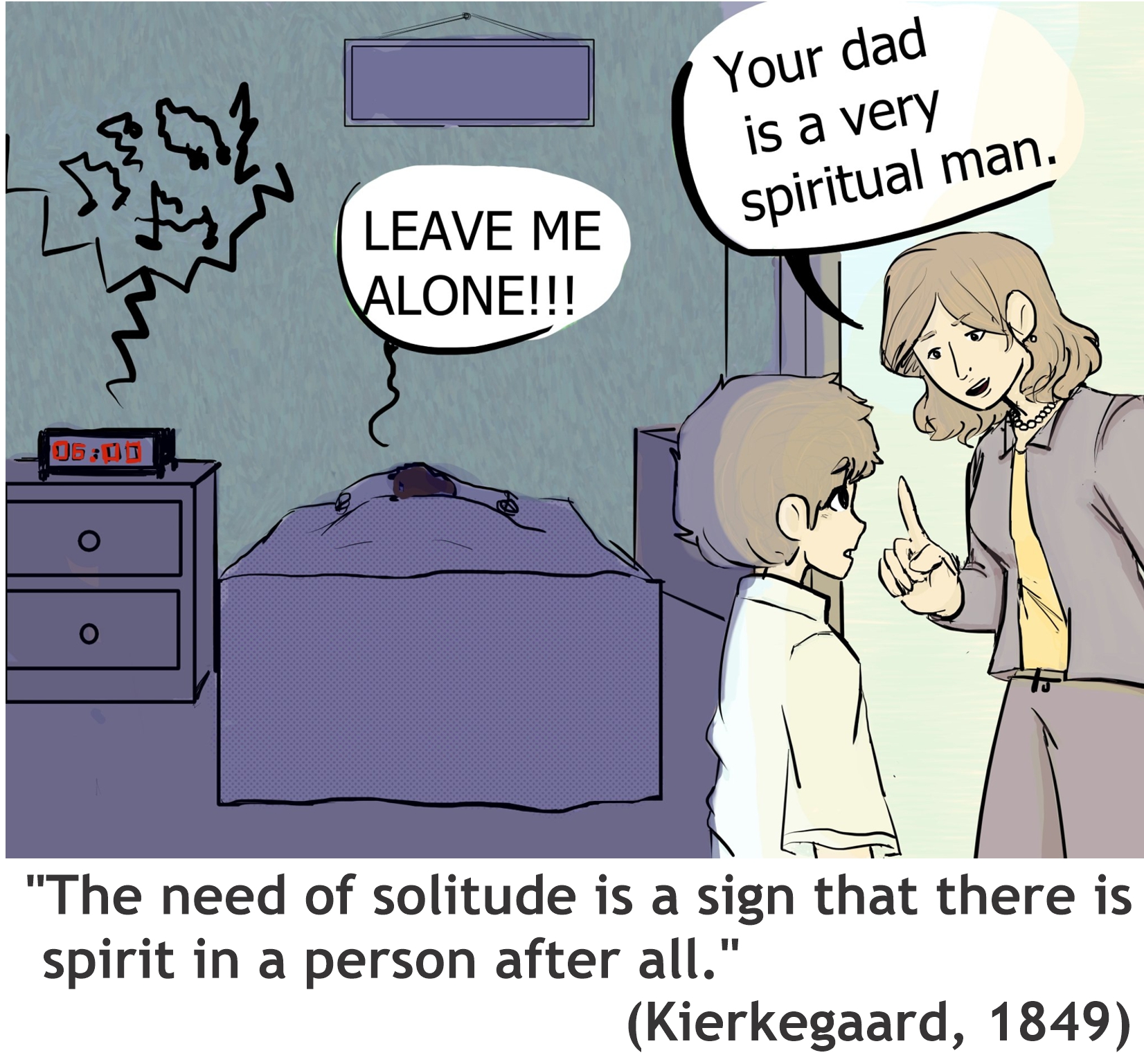

The following text is adapted from Kierkegaard’s description of the second kind of despair. In his usual ironic style, he tells us that the despairer often feels a need for solitude as an escape from his own weakness. Thus, a person’s need for solitude shows that he has enough spirit to feel the need for the eternal, but is too weak to act on this knowledge.

[…] The despairer understands that it is a weakness to take so seriously earthly matters, and that it is a weakness to despair. But then, instead of turning sharply away from despair to faith and humbling himself for his weakness, he becomes more deeply absorbed in despair and he despairs over his weakness. Now he becomes more conscious of his despair. Recognizing that he is in despair about the eternal, he despairs over himself that he is weak enough to give such importance to earthly matters. This now becomes his despairing expression for the fact that he has lost the eternal and himself.

[…] This despair refers to the formula: In despair at not willing to be oneself. Just as a father disinherits a son, so the self is not willing to recognize itself after it has been so weak. In its despair, the self cannot forget this weakness, it hates itself, it will not humble itself in faith under its weakness in order to gain itself again.

[…] And our despairer is introverted enough to keep every intruder (that is, every person) at a distance from the topic of the self, while outwardly he is completely "a real man." He is a university man, husband and father, an unusually competent civil official even, a respectable father, very gentle to his wife, and he is carefulness itself with respect to his children. And a Christian? Well, yes, sort of. However, he prefers to avoid talking about the subject, although he willingly observes, with a melancholic joy, that his wife engages in devotions. […]

On the other hand, he often feels a need of solitude, which for him is a vital necessity – sometimes like breathing, at other times like sleeping. The fact that he feels this vital necessity more than other people is also a sign that he has a deeper nature. Generally, the need of solitude is a sign that there is spirit in a person after all, and it indicates how much spirit there is. People who are purely trivially inhuman, and too human, feel so little need of solitude that like certain social birds (the so-called love birds) they immediately die if they have to be alone for an instant. Just as the little child must be put to sleep with a lullaby, so these people need to be tranquilized with the hum of society before they are able to eat, drink, sleep, pray, fall in love, etc.[…] The introverted despairer thus lives through hours which, although they are not lived for eternity, have nevertheless something to do with the eternal, because they are about the relationship of one’s self to itself – but he really gets no further than this. So when his need for solitude is satisfied, he goes outside himself as it were – even when he goes inside to converse with wife and children. What makes him so gentle as a husband and so caring as a father is, apart from his good-nature and his sense of duty, that he admits his weakness to himself, in his most inward reserves.

If it was possible for anyone to enter his introversion and say to him, “This is in fact pride, you are proud of yourself,” he would probably not admit it to another person. He might probably admit that there is something in it when he is alone with himself. But his emotions when he pictures his weakness would quickly make him believe again that it could not possibly be pride. The fact is that he is in despair precisely over his weakness – as if it is not pride to give so much importance to your weakness, as if the reason he could not endure his weakness was not his desire to be proud of himself.

If one said to him, “This is a strange complication, a strange sort of knot, because your whole misfortune is that your thinking is twisted. Without it, your path could be quite normal: You must travel through the self’s despair to faith. You are right about your weakness, but it is not over this you must despair. The self must be broken in order to become a self, so stop despairing over it.” If one talked to him like this, he would perhaps understand it in a clear unemotional moment, but soon emotion would return to see falsely, and so again he would take the wrong turn into despair.

- Authenticity